U.S. grocery prices jumped significantly after the federal government issued lockdown guidance in March 2020 in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Shutdowns across the globe, instituted to curb the spread of the virus, caused disruptions in shipping food from producers to manufacturing facilities to warehouses and supermarkets and restaurants.

Prices first began to surge in April 2020, but the biggest increases came in 2022, as inflation started to erupted and the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy. These, plus a confluence of other factors, led to the biggest food-price increases in decades.

Related: What Is Sticky Inflation? Definition, Measurement & Example

Why grocery prices surged?

Here are the four biggest causes for the food prices to shoot higher.

Supply chain issues

The pandemic caused disruptions in the supply chain. For some time, workers weren’t able to return to the farms or factories to produce the food that normally would be on Americans’ tables.

Some vegetables, such as kale, were in short supply, and worker shortages led to limited production of cereals and baked goods at food processing facilities. Transportation delays exacerbated these shortages.

Higher demand

Food supplies couldn't keep up with demand, and prices started to rise. Delays in processing meats and eggs, for example, pushed up prices. Globally, borders were closed in many countries, which led to higher prices for imported food products, including coffee and sugar.

Rising production costs

The costs of energy, raw materials, and labor rose, and manufacturers passed those expenses on to retailers. They, in turn, passed them on to consumers. The same phenomenon occurred in transportation: As fuel prices increased, those costs were passed on, eventually to consumers.

The U.S. average price of regular unleaded gasoline peaked at $5.016 a gallon in June 2022, according to AAA. As of May 11, the average price was $3.626.

More consumer finance:

- The 30 most reliable car brands in 2024, according to Consumer Reports

- How much does it cost to die? Cremation, burial plots, caskets, urns, headstones & more

- 20 cities & 15 states with the highest minimum wages in 2024

Reopening the economy leads to accelerating inflation

With the pandemic’s severity subsiding in 2021 and 2022, people wanted to spend, and that led to a sudden surge in prices, from home prices and rents to fuel to groceries because the supply chains that bring food from farm to table weren't ready.

We used the consumer price index for all urban consumers as our basic inflation measure.

The CPI-U moved up from 1.4% in 2020 to 7.0% in 2021. It fell back slightly to 6.5% in 2022 and then to 3.4% in 2023. It's been rising at an annualized 3.3% rate so far in 2024.

By comparison, the subindex for food — the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Food in U.S. City Average — rose 3.9% in 2020. Food prices jumped 6.3% in 2021, and 10.4% in 2022. In 2023, food-price increases slowed, with the index up 2.7%.

Breaking the CPI down into food and other components

Food is a major component of the CPI, but housing is even bigger. We can’t live without food, and every price increase is a dent in the pocket and takes away money that can be used to buy other goods or services.

| Category | Percentage |

|---|---|

Housing (shelter) |

33.8% |

Food |

14.3% |

7.9% for food at home (or food that’s prepared and eaten at home) |

|

6.4% for food away from home (or food purchased at restaurants and other establishments outside the home) |

|

Transportation |

14.6% |

Medical care |

8.9% |

Energy |

7.7% |

Education and communication |

6.7% |

Apparel |

2.7% |

Recreation |

4.3% |

Other goods and services |

7.2% |

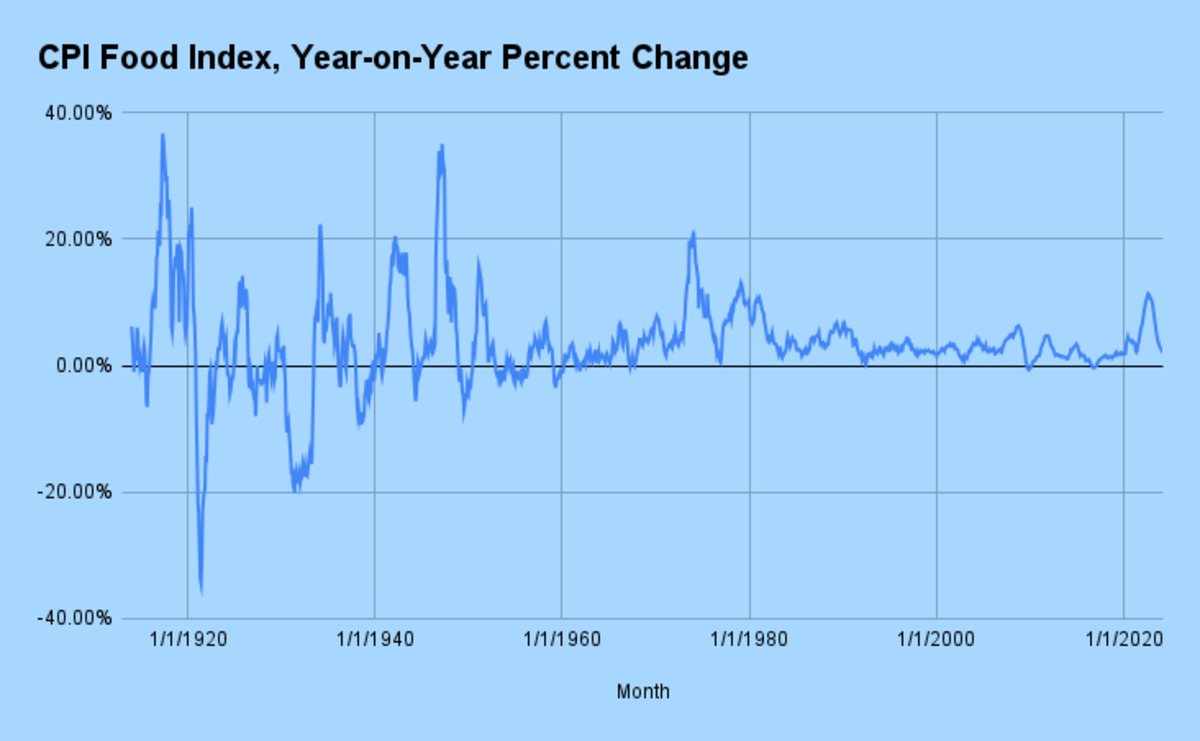

Food prices rise at highest rate since the Great Inflation

How dramatic was the change in food-price inflation in the aftermath of the pandemic?

TheStreet compiled data by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics — the publisher of the CPI — on food prices downloaded from FRED, the giant storehouse of economic data maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, into a Google spreadsheet to show the rapid rise of prices going back decades.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data on St. Louis Federal Reserve website via Google Sheets

The CPI food subindex rose almost 25% between March 2020 and March 2024.

That was the worst since 1979-1983 during the Great Inflation era. The pressures that erupted during the Great Inflation were finally reined in by dramatic interest-rate increases imposed by the Fed under Fed Board Governor Paul Volcker.

Over the 4-year period, the price for eating at home rose 24.7%, while eating away rose 25.6%, most likely due to the rising costs of labor and ingredients at restaurants and other establishments.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data on St. Louis Federal Reserve website via Google Sheets

Prices for meat, poultry, fish, and eggs as a group and cereals and bakery products increased the fastest, by 26.9% and 27.8%, respectively. Prices for candy (up 26.1%), nonalcoholic beverages (up 26.9%), and coffee (up 20.8%) rose faster than fruits and vegetables (up 17.7%), and even dairy products (up 18%) and alcoholic beverages (up 13.2%).

Bureau of Labor Statistics data on St. Louis Federal Reserve website via Google Sheets

Labor shortages at meatpacking plants drove up meat prices. Some food processors, like makers of potato chips and cookies, tried to curb the increase in prices for their products by reducing the size of their packaging but maintaining the same price, in what’s been called “shrinkflation.”

Consumers got a small break. Alcoholic beverage makers refrained from raising prices too fast out of concern that consumers would balk at purchasing expensive beer, wine, and liquor.

The inflation pressures that hit food prices in 2021 and 2022 and a host of other items prompted the Fed to tighten monetary policy. The central bank raised its federal funds rate, its key short-term interest rate 11 times between early 2022 and July 2023 from nearly 0% to 5.25% to 5.5%.

The Fed has wanted to start to trim the rate but has balked because a host of inflation measures, including the CPI, have been stronger than expected this year.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024