At a recent summit of European leaders and their counterparts from the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (Celac), the European Union published a declaration in which it referred to the “Islas Malvinas/Falkland Islands”.

The summit was aimed at re-energising economic and diplomatic relations between Europe and Celac countries and the joint declaration issued at its conclusion was signed by the 27 EU member states and 32 Celac nations. It is not a binding document but the decision to refer to the islands by their Spanish as well as their British name is deeply significant. It happened despite reported efforts by UK foreign secretary James Cleverly to have the islands kept out of the summit declaration altogether and has left the UK angry.

The UK and Argentina have disputed ownership of this southerly archipelago since 1833 – a fact promptly underlined by the responses from the respective governments. UK prime minister Rishi Sunak issued a statement bemoaning the EU’s “regrettable choice of words”. Argentina’s foreign minister Santiago Cafiero, meanwhile, reportedly hailed the EU’s willingness to “take note” of his government’s territorial claim as a “triumph of Argentine diplomacy”.

Argentina has long advocated for dialogue and negotiation. Britain, meanwhile, has consistently maintained that the islands are British and the islanders have voted to endorse that position.

This latest incident highlights the UK’s diminishing influence on EU affairs, post-Brexit. The EU has since clarified that its position on the islands remains unchanged, implying that it continues to recognise British sovereignty, but the shift in language is still notable. Use of the islands’ dual moniker suggests that each name carries equal validity and the UK government has pointed out that to use the name Argentina uses is to question British sovereignty. It has also underlined that this marks a break from the EU’s historical alignment with the UK’s stance. One EU official was quoted as saying: “The UK is not part of the EU. They are upset by the use of the word Malvinas. If they were in the EU perhaps they would have pushed back against it.”

How the archipelago got its names

My research shows that the rhetoric of “rightful possession” is at the heart of the territorial dispute. It is embedded in the act of naming.

With the advent of the European age of discovery in the 1500s, territorial naming – or renaming – became central to colonial practices. It was a means, as British writer James Hamilton-Paterson has put it, of taking ideological control of territory.

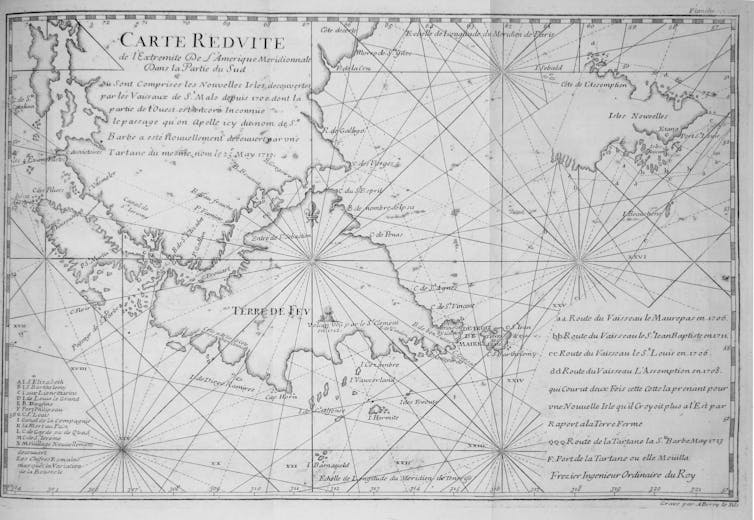

From the 16th century on, various names for the archipelago – the Sebalds, New Islands, Hawkins Maiden Land –- were used interchangeably, each relating to different European expeditions. Often these involved possible but unconfirmed sightings. Other names –- Falkland Islands; les Îles Malouines –- only later gained traction via their presence on maps, highlighting the strategic importance of cartography.

British accounts of the Falklands, from the 19th century onwards, credited the Elizabethan navigator, John Davis, with their discovery, after Davis’s vessel, the Desire, was reportedly driven between the two main islands during a storm on August 14 1592. This has since been disputed by, among others, the legal scholar Roberto C Laver.

The first verifiable sighting and precise plotting dates back to 1600 and is attributed to the Dutch navigator Sebald de Weert. In January 1690, English mariner and captain of the Welfare John Strong made the first undisputed landing. Strong sailed down the sound between the two main islands which he named “Falkland Sound”, after Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount Falkland, then Commissioner of the Admiralty.

By the early 18th century, a shift in British terminology had begun. Maps drawn up by English astronomer Edmund Halley demonstrate how cartographers went from using the name “Seebold de Waerds Isles” to “the Falklands” or “Falkland Islands”.

Eighteenth-century French expeditions, meanwhile, referred first to “les Îles Nouvelles” (the New Islands) and, from 1722, to “les Îles Malouines”, in reference to Saint-Malo, the Brittany port from which French expeditions often departed. It is from the latter that the Spanish name “Islas Malvinas” is derived.

Beyond geography

In his landmark 1993 book, Culture and Imperialism, literary scholar Edward Said writes:

Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.

Islands have always had a certain chimerical quality. Many imaginary islands have appeared on and disappeared from maps, including Hy-Brasil, long purported to be off the coast of Ireland, and St. Brendan’s, charted somewhere in the North Atlantic but never found.

Cartographical history shows even real places, like Ascension Island, shifting shape and position because the absolute position and boundaries of an island can be difficult to ascertain. As shown by the cases of Bermeja Island (dubbed Mexico’s missing island) and Hans Island in the Arctic, over which Canada and Denmark have held a long-running border dispute, not to mention the numerous territorial disputes in the South China Sea, this remains true today.

Place names (or toponyms) often carry great cultural significance. They identify. They connect people to their heritage. They provide a sense of belonging – or alienation. They are emotive signifiers. Some are endowed with a greater symbolic capital or resistance than others.

The case of the Falklands/Malvinas makes this clear. Teslyn Barkman, deputy chair of the Falkland Island’s Legislative Assembly, has urged the EU to “respect the wishes of the Falkland Islanders and refer to us by our proper name”.

However, the very inclusion of this territorial dispute in the EU declaration shows that, post-Brexit, Brussels no longer feels the need to show partnership with the UK on this issue of sovereignty. It signals that the bloc is open to further discussion.

Jennifer Wood does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.