For five long years, academics and self-proclaimed nerds have yearned for the return of JSTOR merchandise. Now, their prayers have been answered. JSTOR’s Gear Store and its highly coveted hats are slated to return in early 2023.

Among individuals that pride themselves on a mix of intelligence and ironic humor, this news may seem like a godsend. Others likely find it baffling. Why would a digital academic library make merch? Even accepting that it does, why would its return be worth announcing like a sort-of geeky Supreme drop?

Among academics and the intellectually curious, JSTOR has made a name for itself as a go-to resource. Founded in 1996, its library has access to over 12 million articles, books, images, and primary sources that span more than 75 disciplines. It’s available in more than 69 countries and 10,000 institutions ranging from universities to public libraries. More than 500,000 articles on the site are free, but, unless you are affiliated with an institution, some articles are kept behind a paywall and cannot be downloaded without JPASS, a subscription service with an annual $199 plan or a monthly $19.50 plan.

The JSTOR Gear Store originally launched in 2011 and was inspired by a college student’s JSTOR tattoo. Items included t-shirts, stickers, a onesie emblazoned with “Future Scholar,” and its bestselling navy blue baseball hat. “Obviously, it's amazing for a brand to see somebody with a logo tattoo,” Liza Pagano, JSTOR’s Director of Brand and Creative tells Input. “It made us realize, ‘Wow, if users would do this, maybe there's some less permanent ways that they could show their love for JSTOR.”

The Gear Store shut down in 2018 to provide the JSTOR team with time to think about partnering with the right vendor. After the pandemic lengthened its hiatus, the store is finally poised to return.

Since 2018, JSTOR hats have arguably become more popular. Although the merch has technically been unavailable, the JSTOR team has continued to fulfill requests from people who’ve reached out via social media and even replaced damaged merch. Authentic JSTOR hats have resold on eBay for more than $200 and inspired a cottage industry of bootlegs. On Redbubble, a retail site that allows independent artists to sell their work, knock-off JSTOR hats can sell for more than $30, twice the price of the original.

One student, a philosophy undergrad named Martin Li, tweeted last year, “i want nothing else in the world but the jstor hat that ran out of stock and never came back.” Their tweet received 43,000 likes and 4,000 retweets. Searching “JSTOR hat” on Twitter reveals many similar sentiments. “When will they drop the JSTOR hat again” reads another tweet complete with a crying face emoji.

“It's taking pride in this interest that, growing up for a lot of millennials, wasn’t cool. A lot of people want to kind of lean into aspects of themselves that they weren’t able to lean into as much when they were growing up.”

Asked about the allure of JSTOR merch, many admirers say the apparel serves as an identifier. Although it may not be tied to a specific sports team like other caps, it does signal allegiance to nerds instead of jocks. Wearing the hat shows not only that you’re familiar with JSTOR, but you also have an active investment in it. In its purest, least ironic form, wearing the hat reclaims nerdiness, specifically a love of books and humanities.

“It's taking pride in this interest that, growing up for a lot of millennials, wasn’t cool,” Li tells Input. “Entering into adulthood a lot of people want to kind of lean into aspects of themselves that they weren’t able to lean into as much when they were growing up”

The hat’s aesthetics accentuate its nerdiness. The hats, while aesthetically pleasing, aren’t cool in the typical sense. Speaking with Input, Aashish Gadani, an artist who sold bootleg JSTOR compares them to “something they would give out at a conference.”

Many of the Redbubble knock-offs call themselves “dad hats,” evoking the dadcore trend that continues today. This trend showcases the functional, anti-fashion style of classic ‘90s/‘00s dads, including chunky New Balance sneakers and T-shirts tucked into khakis with belts. The style reflects a simpler time, disconnected from today’s lightning-fast trend cycle.

JSTOR is likewise a kind of relic, embodying a kinder, more thoughtful ideal of the internet. Like many social media sites, its purported product is the exchange of ideas. However, JSTOR doesn’t prioritize bite-sized, spur-of-the-moment commentary, but meticulous, long-form critique instead.

Even the logo, designed in 1996 by Michael Mabry, directly contrasts with the sleek, futuristic logos of other early internet companies. Mabry wanted to evoke the origins of academia and the ancient roots of education. The capital J surrounded by intricate curls is based on bookplates, used as far back as Ancient Egypt to indicate ownership of a book. The curls represent leaves on the Corinthian columns.

The popularity of JSTOR merch is part of a larger trend of collecting niche merch. During the pandemic, for instance, New Yorkers began sporting hyper-localized merch repping restaurants, museums, and city-specific inside jokes. The Cut dubbed the obsession “Zizmorcore,” ascribing it to a desire for identity and belonging. For JSTOR merch, however, the attraction can be even more tongue-in-cheek.

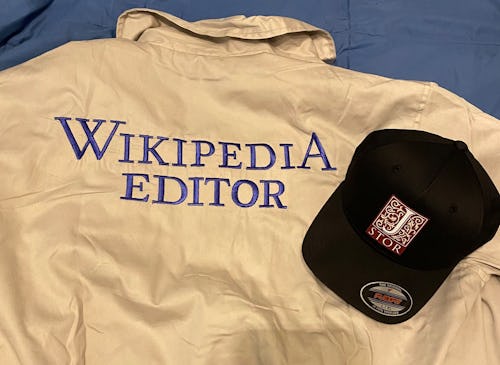

Twitter user @bridespanker recently posted a photo of a JSTOR hat alongside a jacket with “Wikipedia Editor” embroidered on the back with the caption “today’s fit.” The tweet received 27,000 likes and cheeky comments such as “drip too strong” and “studious ass fit.” @bridespanker, who asked to be referred to only by his Twitter handle, tells Input he has a collection of niche corporate merch he calls “absurdist” and a “non sequitur.”

“I think that a little bit of random humor gives people catharsis,” he says.

The passion for JSTOR merch reflects millennials’ surrealist and at times nihilistic humor. The comedic sensibility is evident in everything from silly memes to popular TV shows like Bojack Horseman. In The Guardian, Rachel Aroesti argues that the idea “that the universe is inherently irrational” is “rendered particularly apt by the unpredictable political developments of the past few years.” Millennials have grown up in a world defined by corporate interests where anything can be commodified. The exclusivity of acquiring something as nerdy as an out-of-stock JSTOR hat or even buying a bootleg takes the joke to a meta-level.

“It's funny to buy a bootleg. But then it's even funnier when you find a real one,” Gadani says. “I think the idea of bootlegs is very endearing and funny, even if they're not exactly trying to mimic the real thing. It's like everything is bootlegged. You can get an off-brand version of anything.”

@bridespanker likened wearing company merch to beating capitalism at its own game by taking branding to an extreme. “It’s a statement of consumerism taken to its final level, literally wearing a uniform for a company,” @bridespanker added. “Taking consumerism to its final level in an act of parody.”

This tongue-in-cheek backlash against capitalism is exemplified through the popularity of merch from some of America’s most despised companies. A cap from Lehman Brothers, the company whose bankruptcy marked the 2008 economic downturn, can set you back more than $300. Pants from the disgraced Fyre Festival sold for almost $300, while original apparel from Theranos, the tech company run by convicted scammer Elizabeth Holmes, can fetch $500.

JSTOR’s notoriety pales in comparison to these colossal failures, but the nonprofit does have its detractors. Critics of the platform say the trove of scholarly work should be accessible to all, not stored behind a paywall or limited to people with access to higher education. This critique crystalized when open-access activist Aaron Swartz committed suicide in 2013 after facing a 13-count indictment for downloading massive chunks of JSTOR’s library to distribute them publicly. This story may not be the first thing many people associate with JSTOR, but for some the connection lingers, adding an even deeper ironic twist to their merch.

“I think some people buy it because they think it's ironic and funny to rep something that admittedly has a sort of complicated history,” Gadani says. “With all the, like Aaron Swartz stuff, [JSTOR doesn’t] have the best reputation”

Pagano says the organization has been working on being more accessible with open-access primary source collections and an initiative to bring the database to incarcerated learners. But whether you remember JSTOR as a vital tool for learning or epitomizing the privilege of academia, it remains a defining part of American education.

“I can’t think of anything comparable, which is why I think it’s unique in terms of the college experience,” Gadani says. “There’s only so many tools that are ubiquitous in American schools.”

Pagano says the team at JSTOR embraces the attention, including the memes and the imitation hats. In the lead-up to the store’s reopening, the JSTOR team hopes to maintain its community of vocal supporters. They intend on using a woman-owned, BIPOC-run vendor to sell their merchandise, make sustainable products, and keep their prices accessible.

These decisions don’t come easy, and the JSTOR team understands the importance of taking the time to reintroduce themselves on the right foot. After being overwhelmed by the pandemic, they now have the time to focus their attention on the story. “We finally can take a breath and be like, ‘Okay, maybe we can get back to something,’” Pagano says.

Designers have been dreaming big, drawing JSTOR streetwear mock-ups that include embossed Adidas Stan Smith sneakers. The mock-up includes JSTOR’s logo on the lip of the shoe with curls emanating from its heel.

Whether it’s a Zabar's tote, an Enron hoodie, or a potential JSTOR and Adidas collaboration, what binds the merch trend together is our modern love of remixing. Pagano said the methodology behind streetwear and sneaker collaborations isn’t so different from scholarship. You draw on the past, on what has been done before, and bring it into the context of the present. With fresh eyes, she says, you can create something totally new.