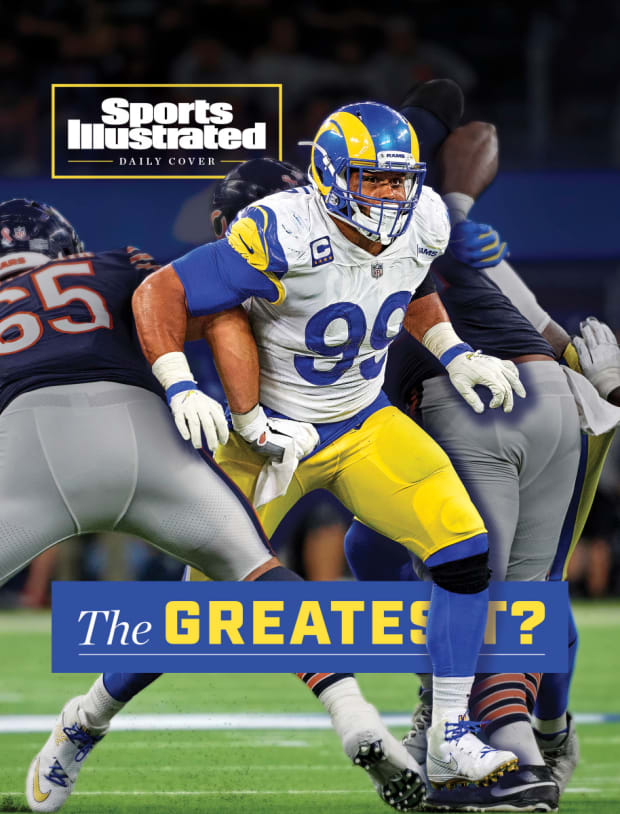

Dante Scarnecchia may be the greatest offensive line coach in NFL history, having coached in the league for 36 years. But when he walked into his positional meeting room before the Patriots played the Rams in Super Bowl LIII, there was still a detectable curiosity as to the elephant in the room: How on Earth was he going to plan for Aaron Donald?

That season, Donald had 20.5 sacks and 41 quarterback hits as an interior defensive lineman and won his second consecutive Defensive Player of the Year Award. Donald was also doing comically extraordinary things such as hurling 300-pound grown men into the backfield with enough velocity to knock over a nearby quarterback as if we were duckpin bowling on a regular basis.

“You can see it on their faces,” said Scarnecchia, about his Patriots offensive line stopping Donald in the Super Bowl. “O.K., what are we going to do here? How are we going to get this done?”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

A few weeks ago, during an editors and writers meeting ahead of the Rams’ season debut tonight against the Bills, we wondered aloud whether Donald was the greatest defensive player in NFL history, or may turn out to be. This is a heady topic. It’s almost impossible to answer. It’s notoriously difficult to compare players across eras, minus a more encompassing statistic that artfully blurs generational lines. As good as baseball was at keeping records, there’s still no way we can understand peak Babe Ruth versus peak Barry Bonds.

Like most modern sports fans, we have become accustomed to greatness, with Donald’s highlights ultimately bringing the kind of numbing sensation you get from years of moderate drinking. It takes more to surprise us, to knock us on our rear ends, even if we should be surprised by almost everything Donald does. Meanwhile, we fold in arguments with older generations, who tend to describe their players and their era more colorfully and bullishly. My personal take is there was simply less information then. They paid more attention, and had less of an ability to instantaneously compare data to the most surprising thing they’d seen all day. A Mickey Mantle home run could resonate with them for a lifetime if they saw it in person. Today, at this very moment, it would rank somewhere between No. 30 and No. 3,000 in terms of what our brain is digesting between its buffet of external stimulants.

With that in mind, we wanted to consult people such as Scarnecchia, who began coaching the offensive line in 1970, breaking into the NFL with the Patriots in ’82. He, like coach Bill Belichick, has an expert ability to remove the extraneous. He does not talk in narratives. A player either poses a problem for him or does not. And a problem is the same now as it was in ’89. Much like a good historian can bridge eras, a smart, tenured football coach can make reasonable comparisons from player to player.

And Donald posed a massive problem for Scarnecchia and the Patriots.

“You can push the protection to his side, minimize the spacing he has to deal with, call runs toward him to allow two guys to maintain control of him.

“But there’s times you [have to leave him single blocked]. And you just say, ‘Oh, man. Come on, left guard.’ You have to come through now. And you have to do everything exactly right. You have to be really perfect.”

The list of individual considerations the Patriots made in that game for Donald specifically was noteworthy, including starting the game with quicker throws to tire Donald out faster, forcing him to utilize his burst off the line when there was ultimately no reward for the effort.

As Donald enters his ninth season, he has almost nothing left to prove, enough so that retirement became a real and believable part of the conversation before Los Angeles’s Super Bowl LVI victory over the Bengals. What’s left is really the reshaping of narratives, for those of us who cannot see the game the way someone such as Scarnecchia does and instantly download a side-by-side comparison to, say, John Randle (Randle, by the way, has put Donald far behind Lawrence Taylor, who is another common nominee for Greatest Defensive Player of All Time, and there are plenty of other worthy candidates regularly bandied about in conversations such as Rod Woodson and Alan Page). For those of us who cannot say with absolute certainty that only a perfect block stops Donald, and know exactly what a perfect block in a given situation looks like.

Reggie White is somewhat universally considered the current GDPOAT and is second (198 sacks) only to Bruce Smith (200) in sacks. Donald is 100 sacks behind White, though he’s played in 105 fewer games. White logged 0.85 sacks per game, while Donald is pacing at 0.77. And … sacks are just one component of all this.

There is a legitimate argument to be made that Donald is already the GDPOAT. There is a legitimate argument to be made that Donald can never be the GDPOAT.

Scarnecchia, like some others, believes if Donald hangs around long enough, he’ll have a shot.

“He will certainly be in the conversation,” he said.

So join us as we spend the hours before Donald steps back embracing debate. Though, around here, there’s no shouting.

Chuck Smith is a nine-year NFL veteran and private pass-rushing coach to the stars. Friends of this site may remember him as Dr. Rush, the Sack Doctor. Smith is a pass-rushing historian who has learned from and played with some of the best defensive players in NFL history, including White. His intimate knowledge of sack artists spans decades.

Von Miller and Maxx Crosby are among his contemporary clientele. He has a video on his phone of a baby-faced Donald before the draft saying that he one day hopes to make it in the NFL.

He understands there is a LeBron James/Michael Jordan/Kobe Bryant/Kareem Abdul-Jabbar element to this debate. We could sit around talking to ourselves in circles when the answer is a little less complex. There are probably not true GOATs but Mount Rushmores, which are the fairest and most encompassing panorama of a sport’s true individual greats.

Smith says Donald is on Mount Rushmore right now. Also on Mount Rushmore are White, Chris Doleman, Warren Sapp, Randle, Julius Peppers, Kevin Greene, Michael Strahan and Taylor.

He considers the late 1980s and early ’90s the “greatest generation” of pass rushers, with only a few modern rushers such as Miller, Donald, T.J. and J.J. Watt and Nick and Joey Bosa invited into that comparative space.

“Aaron fits on the Mount Rushmore, but he’s on the Mount Rushmore with more than just three other guys,” Smith says. “I’ve watched, I’ve studied, I’ve seen all these guys up close. I look at their skill, their impact on the game and their ability to play in each other’s eras. Would Aaron Donald do the same things back in the day? Yes. Would Reggie White do the same things in this era? Yes. His place is solidified as a skilled rusher.

“He’s coming up on 100 sacks as a defensive tackle, which is special. You throw in Defensive Player of the Year awards and the Super Bowl, his ability to turn a franchise around. He’s comparable to Reggie White. Aaron did for the Rams what Reggie White did for the Packers.”

Smith is great because, like a good arbiter, he defends both eras. The case against modern players? In addition to an extra game, NFL teams are passing roughly four more times per game than they were back in 1990, which earns the current generation an advantage. They have about 68 more chances to get to the quarterback. Offensive tackles, Smith said, were largely older, more physically mature and better experienced.

“There’s the Jordan/LeBron thing,” Smith said. “People didn’t shoot the three-pointer back when Jordan was playing. How many points would he have then?”

But this generation had its own unique hurdles worth exploring. Back when White and Bruce Smith were playing, quarterbacks regularly dropped five to seven steps from under center. They spent more time in the pocket. There is also a wealth of information available to coaches far beyond what their predecessors had. In several seconds on a film database, they can download high-resolution clips of every great pass rusher in history and how the best offensive line coaches tried to neutralize them. There are not many “new” ideas in the NFL, but there is more convenient access to the best, old ones.

Donald’s worst game can be shared in seconds. Which means he has been continually forced to evolve along with our understanding of his skill set. More is known about Donald’s individual tendencies, and his likes and dislikes as a player, than we’ll ever understand of White or Smith. It would have taken a quality control coach an entire offseason to develop that kind of Rolodex in the 1990s, cutting and splicing VHS tape together.

Which brings us to the same question we asked Scarnecchia. Knowing all of this, understanding the nuances of each era, is there a way we can blow up Mount Rushmore and be looking at a bronze statue of Donald, flexing and contorting his abdomen into its trademark 12-pack?

“If he gets another Defensive Player of the Year Award, he’s sitting there with Reggie White,” Smith says. “It’s 1A and 1A. Aaron’s path is to continue to get double-digit sacks. He’s on his way to 10 years of 10 sacks or more. There is a path for him.”

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

A good sports argument needs something we can grasp between our fingers, something that makes the idea that Donald may be better than we can reasonably fathom seem real. While winning Defensive Player of the Year three times, Defensive Rookie of the Year and never finishing below fifth in DPOY voting, or reaching first-team All-Pro status in every season of his career but one might suffice, there is better football information available right now than at any point in human history.

Enter Cynthia Frelund, a data science expert for the NFL. Our prompt to her was vague—Hey, might Aaron Donald actually be the best defensive player ever?—and her response was extraordinary (edited slightly for style):

• In a 42-season sample, no player has been double- or triple-teamed more than Donald, who has received two or more blockers on a given play on 56.7% of his snaps.

• In that same 42-season sample, no player has ever generated a better pressure rate on plays when double- or triple-teamed. Donald is causing pressure at a rate of 15.6%.

• Over that time period, edge rushers (and, remember, Donald is largely an interior rusher who can also play defensive end) were double- or triple-teamed at a rate no higher than 52% in any single game, and averaged 51.5%.

• Before Donald, the best pressure rates from players who were consistently double- and triple-teamed were 14.2%, which was a tie between Taylor and White, and 13.8% from Bruce Smith.

For the TLDR crowd, no one has received multiple blockers more than Donald in modern NFL history. No one in modern NFL history has performed better under those circumstances than Donald.

Eric Eager runs research and development for Pro Football Focus, the data site responsible for some of the most significant advancements in the NFL over the past 10 years. Along with colleague George Chahrouri, they developed a football version of WAR (wins above replacement). WAR was a seminal data marker for the sabermetric movement in baseball, and PFF made a version that attempted to wrangle a more complex set of parameters for football (baseball is largely a series of individual matchups, while football is so dependent on hundreds of other factors per play).

We asked him the same question about Donald’s singular greatness.

Last year alone, Donald was worth a full WAR (meaning, having Donald on the roster was worth one more win than if the Rams had employed a league-average defensive tackle). He was, by a very wide margin, the best defensive player in football. There were a handful of players such as Packers safety Adrian Amos and Cowboys linebacker Micah Parsons who finished at roughly ½ a win. The second most valuable defensive interior lineman behind Donald was Cam Heyward, who posted a ⅓ win value.

“In the modern NFL, Donald is without a peer,” Eager said, noting that PFF’s data set goes back to 2006.

For nonquarterbacks, PFF’s WAR metric equates to roughly $50 million in value per win. Donald was, theoretically, more valuable from a monetary standpoint than any quarterback in real dollars. And while quarterbacks naturally generate more WAR (Tom Brady led the league at 4.70 wins above replacement last year), Donald is the only defensive player in their wheelhouse.

This, ultimately, may have gotten us closer in our search to quantify Donald’s greatness than anything else. Donald makes $31.6 million per year as an interior defensive tackle. He is the No. 13 highest-paid player in the NFL earning more per season than Tyreek Hill, T.J. Watt, Davante Adams and Myles Garrett. And, there is a forum by which we can have a discussion about him being underpaid without doubling over in laughter.

Isn’t that, ultimately, what makes one the greatest player of all time? That you can’t think of a number high enough to pay him? That you can’t think of an offense that slows him down? That you can’t quilt a network of two or three players together who can stop him?

Watch Aaron Donald and the Rams live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!