It’s an unusual brand of basketball torture, being pulled away into open space, out onto an island with a 7'3" teenager who is not only dribbling a ball back and forth between his legs, but also sizing you up as he goes.

Victor Wembanyama has lulled Limoges power forward Wilfried Yeguete out beyond the three-point line on the left wing and entrapped him in a moment. Rocking side to side, Wembanyama stutter-steps to his left. Then, on a half beat, he floats off his left foot, raises the ball over his head and flicks it with his right hand toward the rim, all in one motion.

There’s no name for this technique yet. Wembanyama has just unveiled it, an improbable, perfectly balanced, one-legged running jumper from deep range. It resembles something someone might invent in the final dregs of a game of H-O-R-S-E, but he’s spent the past several months privately honing this particular move—one that stuns both his defender and the sold-out crowd at the Palais de Sports Marcel-Cerdan.

Watch the full video here.

The make is all twine, and the arena erupts. This is what they came for. This is why fans lined up around the block on a brisk November evening in Levallois, why they jockeyed for prime position over a bright-yellow guardrail some 20 feet above the court to watch him warming up and why throngs of scouts have packed in behind the basket all season. To be dazzled by not only the most promising talent in France, but also the premier basketball prospect on Earth.

This, as they call it here, is Wembamania.

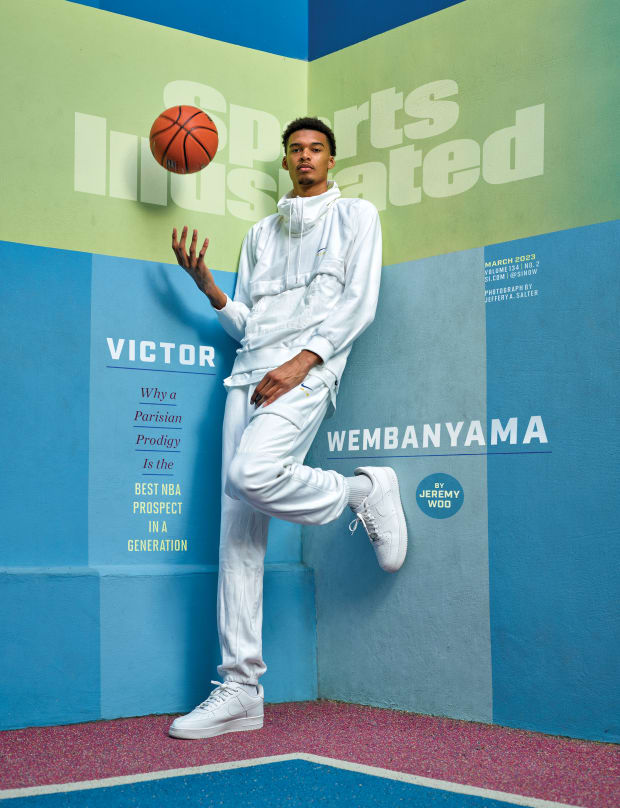

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

Following Wembanyama’s arrival on the global stage with a pair of spectacular October showings against the NBA’s G League Ignite team in Las Vegas, months before his 19th birthday, every minute of his final season in his home country has been dissected. The boy wonder has transformed his team, Metropolitans 92, into a French league contender and appointment viewing. Would-be suitors across the NBA are sweating May’s draft lottery. The club has been selling out its modest, 30-year-old, 2,800-seat arena, where a cartoonish yellow wasp mascot draws cheers from groups of schoolchildren munching chips out of brown paper sacks and Wembanyama jerseys scatter the stands. Not even the team was fully prepared for the wave of demand his growing stardom would bring: Lower-grade replicas are on sale, but Metropolitans’ official Puma kits must be specially ordered.

On this night, everyone goes home satisfied: Wembanyama methodically operates toward a final line of 33 points, 12 rebounds, four assists and three blocks in a 78–69 win. After the buzzer, he dances at center court encircled by his teammates, his pointer finger raised to his forehead, like a unicorn.

Minutes later, a dozen or so French reporters pack into a small press room beneath the stands, where the opposing coach is fielding questions. “Am I frustrated that we haven’t been able to stop it?” Limoges coach Massimo Cancellieri asks in French. “Has anyone ever been able to do it?”

Cancellieri pauses and rubs his bald head. Then he spreads his arms, extends his left pointer finger and clicks his thumb, as if peering down an imaginary scope. “The only way would probably be to pay a sniper.”

This is the Wembanyama effect: He leaves everyone searching for new ways to describe whatever it is they’ve just encountered.

In NBA circles, scouts have privately thrown out comparisons to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. LeBron James, following Wembanyama’s two exhibition games in Vegas, described him as an “alien.”

“I’ve seen him make five threes with the right hand in a row, switch to the left and make five threes,” says Stanford’s Maxime Raynaud, who grew close with Wembanyama during a shared final season at Nanterre, Victor’s first club. “That’s the craziest s— I had ever seen in my life.”

There’s a Bunyanesque air to Wembanyama’s ever-growing list of talents and achievements; folklore’s foremost lumberjack stood just 7 feet flat (in shoes, one might imagine). But his level of play now transcends conjecture: The whole basketball world knows, barring some unfathomable occurrence, Wembanyama’s name will be the first called on draft night in June. Passing on him would be a “fireable offense,” as some scouts have put it.

What happens after that will be up to him.

As was written 21 years ago in this publication about a teenage LeBron, the same applies to Wembanyama:

He’s almost there, but not yet.

Lucas Peltier/USA TODAY Sports

Life across the Atlantic awaits, future area code unbeknownst. For now, Wembanyama lives a relatively quiet and familiar life in Paris, not far from where he grew up in Le Chesnay, a pleasant suburb adjacent to the palace at Versailles. He can no longer move around in anonymity, relying on a private driver and occasionally a bodyguard. Wembanyama is still settling into fame and all it brings but wears it with an unusual air of calm, particularly for a teenager.

“When you know who you are, you know where you can go,” he says, sitting in a small cafe on Ile de la Jatte, a short walk from his team’s arena. “And that makes it easier.”

Pulling a small dining table back several inches to make room for himself, Wembanyama takes a moment to reflect on his whirlwind season to date. His surroundings will soon change. But this modest, leafy islet on the Seine offers a respite. La Jatte was made famous by French painter Georges Seurat, who shifted the paradigm of his time by pioneering a pointillist style that abandoned expressive brushstrokes for a painfully technical approach—one that ultimately stood the test of time by taking a risk in its execution and scale. Perhaps Wembanyama’s task ahead is not so different.

His sublime mix of skills fascinates. A gargantuan perimeter player who can handle, pass and shoot like a guard but also patrols the paint true to size. Earlier this season, he erased a two-on-one break by forcing a guard to throw a lob, then running to the other side of the rim to swat the other guy’s attempt. Wembanyama captivates imaginations while implementing his own.

“I can’t really take role models,” explains Wembanyama. “Because when you’re 6'2" [versus] 7'3", it’s not the same sport. So, the way I want to play, I got to innovate and just create new things.”

And, so, while he could take the rest of the season off, rest his body, pick out a suit and brainstorm the best way to dap up Adam Silver when the time comes, Wembanyama and his agents, Bouna Ndiaye and Jeremy Medjana, have flatly rejected that notion. His tools and skills would have let him coast to top-prospect status, but the fact that he’s putting together a dominant campaign doesn’t hurt. His last year in France is a platform to work on his craft.

“I gotta diversify my skills even more so people don’t get bored,” he says. “I want to exceed the expectations.”

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

Basketball wasn’t forced onto Wembanyama or his siblings at an early age, even though their father, Felix, who stands around 6'6", was a former track-and-field athlete, and their mother, Elodie de Fautereau, 6'3", was a former player and youth coach. But eventually it stuck with all of them: Victor’s older sister, Eve, 21, now plays professionally for Monaco, and his younger brother, Oscar, 15, last year joined the youth setup at Victor’s previous club, ASVEL.

Victor was a precocious child who learned to read at age 3. He picked up basketball a few years later and, by 9, was helping his mother coach kids his age. He ran on a higher competitive frequency and, at age 10, joined the youth setup at Nanterre, a modestly sized club in the near west suburbs of Paris. He was not yet a prodigy, still playing soccer and pursuing other hobbies, but there was little question he was passionate. His development soon fell under the purview of Karim Boubekri, one of Nanterre’s youth coaches and a self-described “psychopath” when it comes to the finer points of skill-building. “When they’re kids, I’m obsessed with their ability to handle the ball properly,” says Boubekri, speaking through a translator.

Boubekri came of age playing street basketball in the ’90s, equally inspired by And-1 mixtapes and NBA guard play. He came across a copy of Pistol Pete’s Homework Basketball, a four-VHS box set featuring Hall of Famer Pete Maravich that taught the fundamentals of dribbling and ball control using creative and unorthodox drills, which he cites as the foundation of his own coaching style. And thus Maravich’s famously improvisational style of play made its way to Paris—and, eventually, into the basketball DNA of a gangly, 6'6" preteen.

Boubekri’s marathon training sessions typically began with at least two hours of ballhandling work. He demanded his players bring three items to each practice: a pair of soccer goalkeeper’s gloves, a plastic bag and a jump rope. Fail to do so and run 30 laps around the court. The gloves helped develop finger precision, while the plastic bag was tied around the ball, forcing the kids to bounce it forcefully. The rope was simply for jumping. Players would switch between weighted and regular balls. While Boubekri’s approach was intense, he kept his team engaged and diminished the monotony of the work. “That taught us rigor,” Wembanyama says.

Boubekri recalls Wembanyama making huge strides in their first year together, gaining comfort with the ball in his hands and confidence experimenting in games. What impressed him most was Victor’s mind.

When Nanterre would travel to tournaments, to pass time, Boubekri would often read off Trivial Pursuit cards at random, to test his players, particularly Wembanyama, who had a wide range of interests—from science to comic books to art—and esoteric information at the ready. “Victor used to answer the weirdest questions,” he recalls.

On one occasion, as several players huddled inside a hotel room, Boubekri pulled a card he knew would stump him.

Watch the full video here.

“What bird can fly backwards?” he asked.

Naturally, Wembanyama had the answer: le colibri—the hummingbird.

“They were flabbergasted,” Wembanyama recalls. “Karim thought I was joking. Like I had just guessed a random bird.”

Those around Victor marvel at his capacity to store information. “He’s thirsty for knowledge,” says Timberwolves star Rudy Gobert, who met Wembanyama seven years ago and has since become a mentor. Boubekri notes his former pupil’s ability to learn something in a drill one day and unveil it in a game the next. He believes his unusual recall ability and fluid muscle memory work in concert.

“He’s able to reproduce moves very quickly,” he says. At Nanterre, Wembanyama played all five positions. “He’s always been able to try risky things. ... Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, but he’s always been very calm and poised.”

That polymathic skill set transcends the hardwood: Wembanyama also taught himself English and speaks it comfortably, hitting hard R’s and -th sounds with minimal trace of an accent, despite having been to the United States only twice, both in the past six months.

In Wembanyama’s words, “I learn something one time. I’m gonna apply it for the rest of my life.”

Before entering high school, Wembanyama turned down an offer to join Barcelona, instead taking classes near Nanterre’s facility and later pulling double duty at INSEP, the esteemed French development program that helped produce Tony Parker and Boris Diaw. By the time he left Nanterre in the summer of 2021 for ASVEL—the Lyon-based club owned by Parker—he’d been labeled the next great French prospect, winning Pro A’s Best Young Player award at 17.

During his lone year in Lyon, Wembanyama again earned best young player honors, and ASVEL won the league for the 21st time. But Victor logged just 17 minutes per game on a veteran-heavy team and played a more travel- and game-heavy EuroLeague schedule. He struggled at times, battled minor injuries and saw his season end early due to a tear in his psoas, a small back muscle, that required multiple months of rest and recovery.

Conscientious of his health and long-term interests, Wembanyama, along with his agents, thought it best to opt out at ASVEL and pick a new situation for his final season before the draft. They agreed to forgo the prestige of the EuroLeague for a longer view, ensuring that he’d receive the playing time, rest and individual care necessary to prepare his body and skills for a long, healthy NBA career. Moreover, Wembanyama wanted to prove himself as a focal point of his next team.

Says Ndiaye, “Victor was basically feeling that he was not challenged.”

Watch the full video here.

Metropolitans, a team that had never finished higher than third in Pro A, offered the best opportunity. At the time, the club had only a few players under contract, allowing the roster to be built out around Wembanyama’s abilities. He would stay local, play major minutes and manage his workload as necessary. The team hired a trainer away from another French club, Pau-Orthez, primarily to work with him. “Victor needed someone to spend all his energy and focus on him only,” Ndiaye explains.

Metropolitans coach Vincent Collet, who had previously sent in his letter of resignation, quickly changed his tune upon hearing news that Wembanyama was coming. “I [kept] going, because this is something very special, unique,” says Collet, who was ready to focus full-time on coaching the French national team in preparation for the 2024 Paris Olympics—a potential watershed moment for a program that will, presumably, field Wembanyama as a principal player. “I will never be in this position [again] in my career. And if I can help him to reach what he can reach, I will be very, very happy.”

To date, the season has been a near-perfect storm of growth, opportunity and freedom. Wembanyama has become the league’s MVP front-runner, leading his team to second place in the standings as of Feb. 20. He also received his first senior call-up to the French national team in November, helping lead Les Bleus to two wins in qualification for the 2023 FIBA World Cup. In Europe, teenage players are rarely given minutes and shots. Wembanyama has fully justified both, coming up with winning plays while still exploring his own limits. He’s taken a big step forward as a shooter and eclipsed last season’s per-minute production.

Asked whether this is all proof of concept—that he can hoop the way he envisions and still win big—Wembanyama smiles and puts it simply: “As long as I score.”

“He wants to play a certain way,” says Diaw, the NBA veteran and champion who now serves as general manager of the French national team. “He has a vision, basically, to do what he wants to do, in the way he wants to accomplish it. But at the same time, he’s not disrespectful or just doing his own thing. He’s still coachable. And that’s very important.”

Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images

Wembanyama cites the Warriors of the 2010s as a model for the type of basketball that inspires him: They won, they enjoyed themselves and they did it in style.

“Taking, like, bad or weird shots, it isn’t new for me,” Wembanyama says. “You can ask any coaches I’ve played for. They’ve seen me do crazy stuff. Sometimes they thought I was crazy.

“Something I’m proud of in my life is that I’ve kept [going] this whole time. And it required a lot of mental strength.”

Wembanyama has also received support from retired NBA center Ian Mahinmi and Gobert, who have offered on-court insight, off-court counsel and, sometimes, clothing that actually fits. During Victor’s early teen years, Mahinmi mailed him a loaded suitcase full of hand-me-downs and unworn gear. (“In a few years, the tables might reverse,” says Mahinmi. “He might send some Victor Wembanyama clothes to my house.”) And last summer, after Wembanyama’s baggage was misplaced at a Paris airport on a trip to San Diego, Gobert came to the rescue. From his offseason home in Los Angeles, Gobert stuffed a suitcase full of jeans, shirts and shoes, and sent a special delivery in an Uber all the way down Interstate 5. Once a skinny 7-foot teenager himself, Gobert often reminds Wembanyama to stay patient, take care of his body and enjoy the journey.

“I know he’s gonna keep doing the work, because he knows where he wants to go,” says Gobert. “He doesn’t just dream about it. He doesn’t just think that everything around him will happen because he’s Victor. He knows that he has to work harder than everybody else.”

First, there’s a title to chase, a lottery reveal and the draft itself—the last of which figures to be the least suspenseful of the three. By all accounts, he’s managed to keep things in perspective. He carves out time to read before bed each night, specifically to take his mind away from basketball. He prefers fantasy and science fiction. He began meditating daily in high school and creates space in his day to visualize whatever requires his attention. Still, he’s working on delegating his deluge of tasks to his parents and agents, rather than putting everything on himself. There are busy days when he chooses not to touch his phone at all.

“I got so much stuff going through my mind,” Wembanyama says. “I’m never bored.”

“When you’re an abnormal person—when you’re tall—to excel, you first have to be comfortable with yourself,” Mahinmi adds. “For him to be so special, and to be already so comfortable so early ... it’s a very rare maturity.”

Wembanyama just wants to keep things fresh. To keep showing people who he is, to show something new every time. “There’s a fire inside of me, a love,” he says. “Something that’s gonna push me my whole life, I know. I mean, nothing’s gonna stop me.”

He prefers to keep his motivations to himself, for now. Maybe he’ll discuss them at a later date, an ocean away.

“I’m gonna be around for a long time,” Wembanyama says.

He’s not quite here yet, but he’s on the way.