When Americans picture a chaplain, many of them likely think of someone like Father Mulcahy, the Irish American priest who cared for Korean War soldiers in the classic TV show “M.A.S.H.”

The reality is much more complex. Today’s chaplains are diverse in gender, age, religious background and sexuality. They serve people from all backgrounds, including those with no affiliation. And their roles may become more significant as more Americans step away from traditional religious congregations. Three in 10 adults in the United States say they are atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular.”

I have spent the past 15 years interviewing, shadowing and writing about chaplains: religious professionals who work outside of congregations in health care, the military, prisons, higher education and other institutions. My latest book, “Spiritual Care: The Everyday Work of Chaplains,” describes who they are, what they do and how it connects to broader aspects of American religious life. In a recent survey that colleagues and I conducted at Brandeis University in partnership with the polling firm Gallup, we found that a quarter of people in the U.S. have been assisted, counseled or visited by a chaplain at some point in their lives.

Brief history

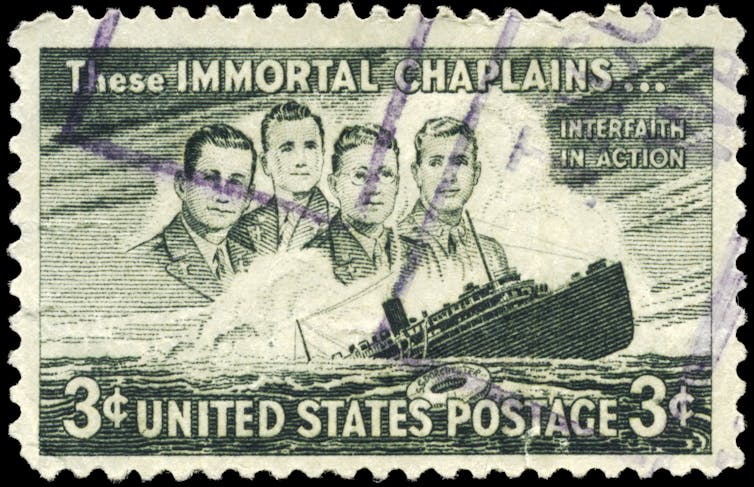

In the U.S., chaplains have been present in the military since the Revolutionary War – initially all Christians. Jewish leaders began to work as chaplains with the advent of Jewish hospitals in the 19th century. In 1861, at the start of the Civil War, a rabbi named Arnold Fischel lobbied President Abraham Lincoln to let Jewish chaplains serve in the military. Lincoln stretched the phrase in federal legislation that required chaplains to be of “some Christian denomination” far enough to formally include Jews as chaplains in government positions for the first time.

The number of non-Christian chaplains has increased ever since. While rabbis frequently visited Jewish inmates, it was not until 1895 that New York state funded an official Jewish chaplain position in the state prisons.

Non-Christian chaplains began appearing on college and university campuses in the 1920s. Today, there are campus chaplains from a broad range of religious and spiritual backgrounds, including humanists who see and emphasize the goodness in all people. They are often able to quickly connect with young people, one-third of whom are not religiously affiliated.

Chaplains have become increasing diverse in other ways, as well. Little has been written about chaplains of color, for example, but African American newspapers suggest that the first Black chaplains served in the military, which was segregated until 1948.

The work today

Today chaplains work in a variety of settings. Beyond the military, federal prisons and veterans’ centers, they are also present in most health care organizations, and places as surprising as the Olympics, research stations in Antarctica, airports and some polling places.

In interviews I conducted with chaplains in greater Boston, all said they work around end of life care, and almost all engage with people’s big-picture life questions – what one chaplain described to me as people’s peripheral vision, the questions hovering just out of sight until a crisis forces them into view. Rather than offering answers, chaplains offer a listening ear. Describing her work in a hospital, one explained her role as creating “a bit of a holding space” and to “validate what a person is feeling and give them some sense of hope or stability in the midst of chaotic times.”

According to our recent survey on demand for chaplains’ services, about half of people who connected with a chaplain did so in health care settings, including hospices. Respondents said that chaplains listened to them, prayed, offered spiritual or religious guidance, or comforted them in a time of need. “He was just so compassionate with my mom and I when we lost my grandfather, and it was a sudden loss,” one participant recalled of meeting with a chaplain. “I knew then God had sent him there to help me deal with the pain and loss.” Another said: “We talked for hours and he truly seemed to understand the path my life had been on. I will never forget his kindness!”

Others said chaplains helped them negotiate conflict, advocated on their behalf, or directed them to resources. Loss, mental and emotional health, death and dying, and dealing with change were frequent topics of conversation. Respondents described chaplains as compassionate, good listeners, knowledgeable, helpful and trustworthy. Those who were not religiously affiliated interacted with chaplains in similar ways as those who are not.

Religious leadership looking forward

In many churchyards across the U.S., “for sale” signs have been hammered into the ground as places of worship fail to keep afloat. Attendance and membership have been declining for years, and many congregants who switched to virtual attendance during the pandemic are not coming back in person.

As membership in formal religious groups continues to decline, enrollment in theological schools is shifting, with growing numbers of new students and programs focused on chaplaincy as opposed to more traditional work in a congregation. About a quarter of new students in the Master of Divinity programs at Boston University and Union Theological Seminary in fall 2022 were in a chaplaincy track. That number is closer to three-quarters at Iliff School of Theology and at Emmanuel College in Canada.

Chaplains have long provided spiritual support, and continue to do so as religious demographics shift. They meet people as they are, where they are, and they will provide more and more spiritual care for the future. Closed churches do not signal the end of religious leadership, but a change in where and how it is provided.

Wendy Cadge receives funding from the Charles H. Revson Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.