Workers in several of Britain’s key service sectors are striking in what is being called the new “winter of discontent” as cost of living pressures clash with below-inflation pay offers.

Many strikes, such as that of the Rail, Maritime and Transport Union (RMT), have been going on for months, with warnings union members will vote to take their fight far into 2023.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said 417,000 working days were lost to strikes in October, the highest monthly total since November 2011 saw mass public sector walkouts over pension reforms.

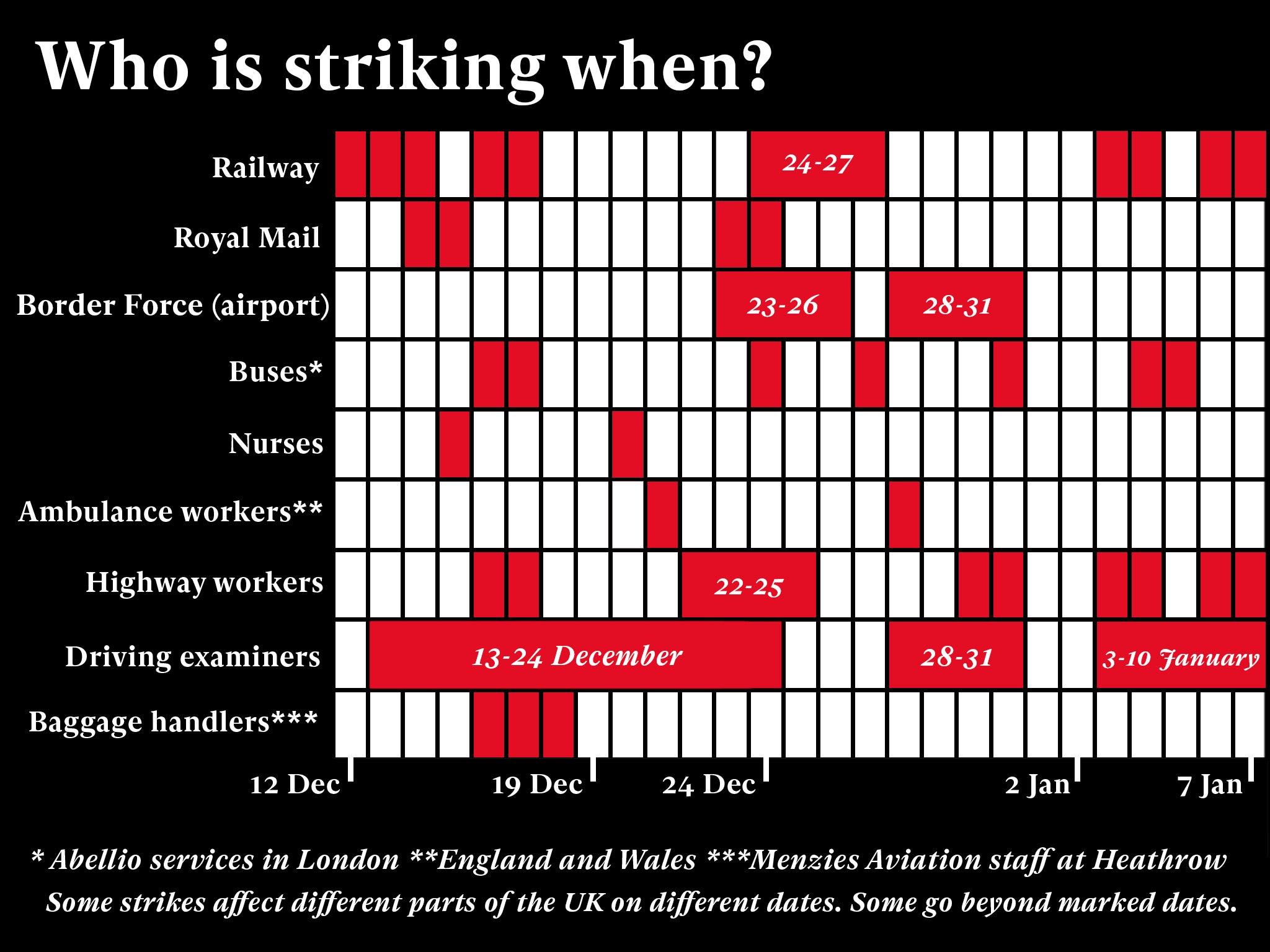

There was only one day this month – by The Independent’s count – on which no major action was planned, Saturday 10 December, setting the path for mass disruption into the new year and leading the government to take desperate measures to avert any potentially damaging impacts.

A thread that binds every striking worker this winter, whether a nurse, a rail worker or a driving examiner, is pay – but each profession has its specific gripes.

Here, The Independent has compiled the factors driving disputes between unions, companies and the government.

Royal Mail

More than 100,000 Royal Mail workers have walked out during action so far this year.

The bitter dispute between members of the Communications Workers’ Union (CWU) and bosses over pay and conditions remain unresolved and there are plans to ballot members in the new year for more industrial action.

The CWU argues that Royal Mail workers had a below-inflation 2 per cent pay deal imposed on them.

The union also accuses the company of reneging on an agreement made last year on the direction of Royal Mail in a changing delivery market.

Andy Furey, acting deputy general secretary of CWU, said the union’s recent offer to Royal Mail was “thrown back in our face” and there are “no further talks planned at this stage”.

Mr Furey said the union wants to ensure the universal service obligation is protected, which recognises Royal Mail’s obligation to deliver across the UK six days a week, with one price for anywhere and to 30 million UK addresses.

“We are also protesting the attacks on jobs,” he said. “Royal Mail want to make many of our members compulsory redundant.

“They want to make at least 10,000 job losses, we reckon it’s probably double that, and we are after a better pay deal.”

Royal Mail made what it called a “best and final pay offer”, worth up to 9 per cent over 18 months, on 23 November, by which time strikes had already been going on for more than three months.

It made several other offers, including more generous voluntary redundancy packages, which were presented as concessions but which the CWU deemed to be betrayals.

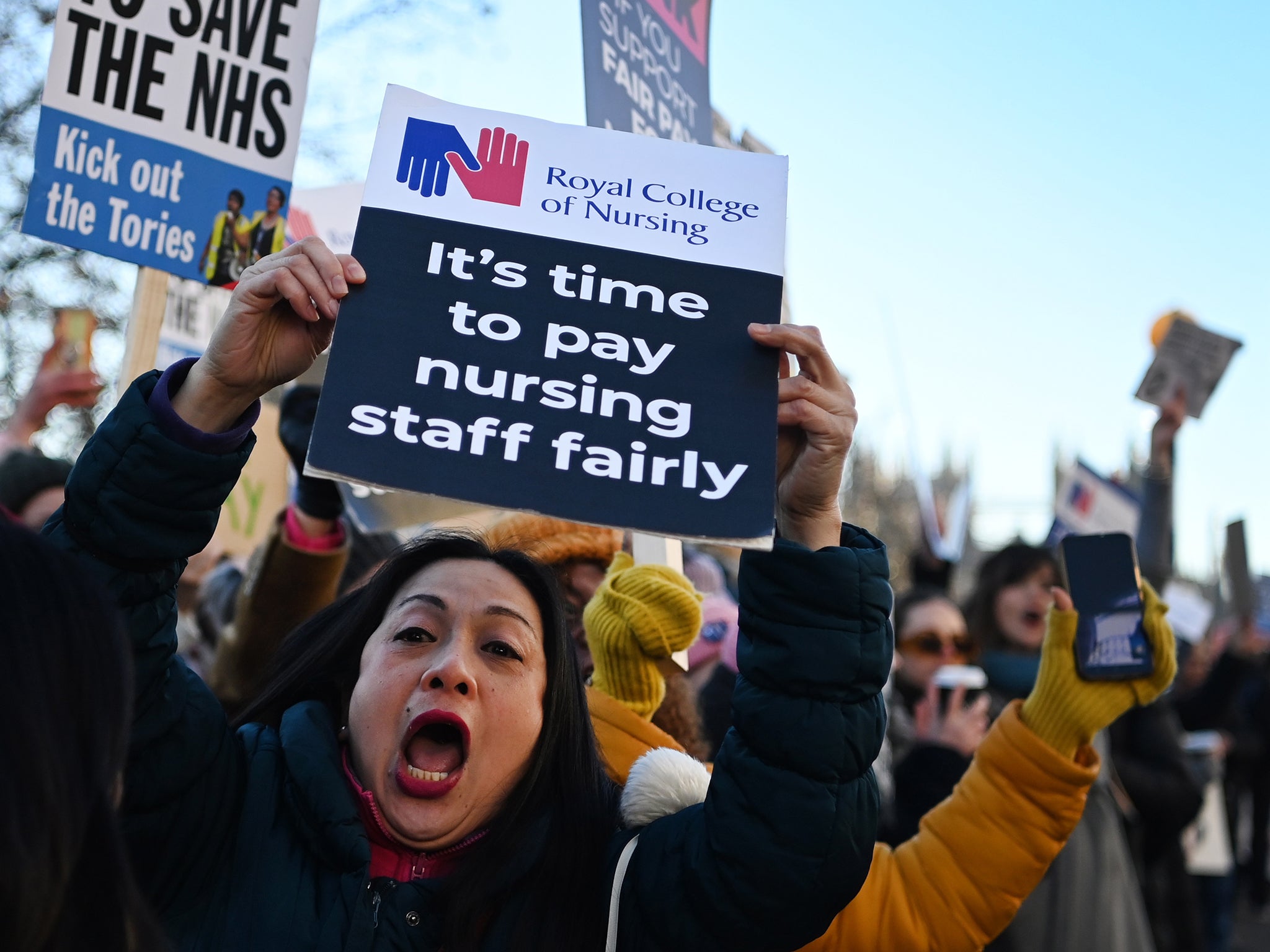

Nurses

Nurses took the unprecedented decision to strike this winter over pay and conditions, with back to back strikes planned for 18 and 19 January.

Earlier this year, nurses were offered a pay rise of around 4 to 5 per cent along with other public sector workers.

Most full time nurses in the NHS would get a salary increase of around £1,400. New nursing staff, however, would see starting pay rise by 5.5 per cent to £27,055.

The health secretary, Steve Barclay, said the government was sticking to the recommendations of the independent NHS Pay Review Body – though reports after the second strike day on 20 December said the government could fast-track a pay rise for NHS staff.

The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) described the 4 per cent basic pay increase for most nurses a “grave misstep by ministers” when it was announced in the summer.

The RCN has been calling for a pay rise at 5 per cent above RPI inflation, which by the latest measure, would be nearly 20 per cent. However, the union has indicated it would accept a lower offer.

The union has argued that low pay is driving “chronic understaffing” which puts patients at risk and leaves nursing staff overworked, underpaid and undervalued.

Members of the Unite and Unison members in Scotland accepted an offer of between 2 and 11 per cent for NHS workers including nurses, with an average rise of 7.5 per cent. RCN members in Scotland rejected the offer.

Unison said it would consider accepting a similar deal for the rest of the UK.

Railway

Network Rail staff who belong to the RMT union have stopped work as part of a dispute that has rumbled on for six months.

Alongside the striking Network Rail workers, other RMT staff working for 14 train operators have walked out in a separate row with the Rail Delivery Group.

On 4 December, Network Rail made an offer. Members of the Unite union accepted it, and those employees have called off planned industrial action. But the RMT put the deal out to a referendum of its members with a recommendation to reject it.

Network Rail offered RMT members a 5 per cent pay rise this year, and a 4 per cent pay rise in 2023 (9 per cent in total).

RMT members are looking for a “negotiated settlement” but have not put a number on what they expect in terms of a pay rise.

In reference to the latest Network Rail offer, RMT general secretary Mick Lynch said it was “substandard”.

Ambulance workers

The GMB, Unison and Unite unions have coordinated industrial action across England and Wales after accusing the retrospective governments of ignoring pleas for a decent wage rise.

Unite said the action was a “stark warning” that it must stem the crisis engulfing the NHS following ministers’ deliberate 12-year assault on pay.

After walking out on Wednesday 21 December, Unison decided to take two further days of action on 11 and 23 January.

The workers, including paramedics and emergency call handlers, are pushing for an increase above the 4 per cent received earlier this year.

GMB, which said 10,000 of its ambulance members backed walkouts across nine trusts, welcomed the chance to meet Mr Barclay, the health secretary, but said “he needs to talk pay now”.

The first strike, on 21 December lasted 12 hours, but the two Unison strikes next month will last 24 hours each.

The health secretary said meeting unions’ pay demands would mean taking money away from frontline services.

“Strikes are in no one’s best interest least of all patients and I urge unions to reconsider further strike action before walkouts have a worse impact on patients,” he said in a statement.

Unison general secretary Christina McAnea said she would meet the health secretary but urged the government to “stop using public safety fears as a smokescreen for its own inaction”.

“It’s only through talks that this dispute will end,” she said. “No health workers want to go out on strike again in the new year.”

Border Force (airport)

The Public and Commercial Services (PCS) union is taking industrial action from 23 December until the end of the year, with the exception of 27 December, with up to six months of walkouts warned by the union.

Affected workers will include Border Force staff at airport passport control desks, leading to fears of travel chaos over the busy Christmas period.

Mark Serwotka, the PCS general secretary, said: “They have been offered just a 2 per cent pay rise at a time when inflation is running at over 10 per cent.

“They are determined, they are strong and they been left with no other way of expressing their concerns about the cost of living crisis than to take strike action.”

Teachers

Teachers in Scotland are striking over a below-inflation 5 per cent pay rise.

NASUWT, the teachers’ union, announced on Monday it would launch strikes in primary schools on 10 January and in secondary schools the following day.

The union is calling for a fully funded 12 per cent pay award for 2022/23 and said that the current pay offer tabled by ministers and Cosla amounts to a further real-terms pay cut.

The Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS) union is also staging strike days between 16 January and 6 February, staggered across different parts of Scotland.

Highway workers and driving instructors

Road traffic officers and control room operators working for National Highways are striking on several days over three weeks from 16 December.

Driving instructors will be on strike most days between now and 10 January.

Workers from both professions represented by the PCS are taking action over below-inflation pay rises, complaining that years of small increases, or sometimes pay freezes, had left them particularly vulnerable to inflation.