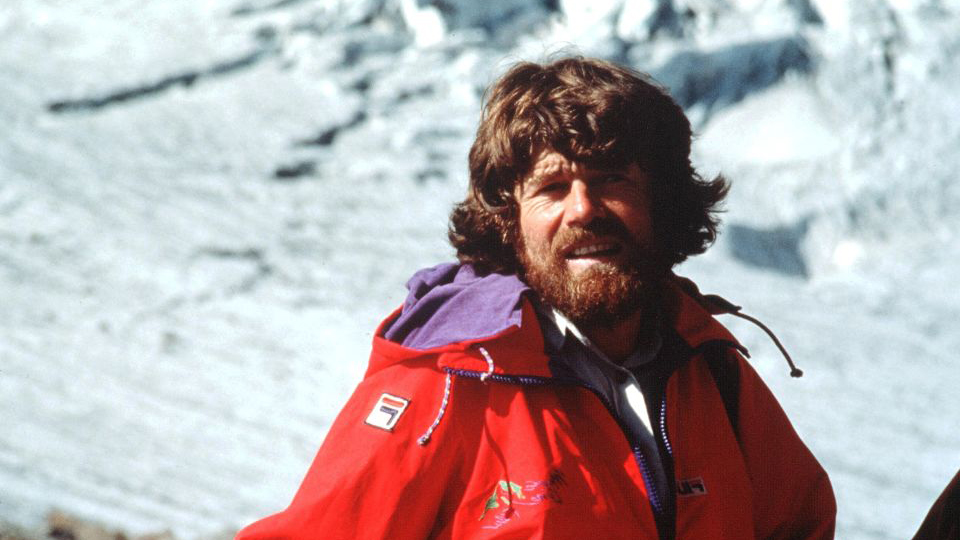

“A tourist follows a trail, a mountaineer finds one.” Outspoken, charismatic, daring and brilliant, few individuals hold the respect of the mountaineering community like Reinhold Messner. Widely regarded as the greatest mountaineer of all time, Messner’s achievements and the style with which he climbed some of the world’s most challenging peaks have made him a modern-day doyen. If Messner says your climb was worthy of respect, you’d better believe it.

His list of feats is long and varied, but let’s start with the headlines. In 1980, he was the first person to climb Everest solo and without supplementary oxygen. Six years later, he ticked off Lhotse, becoming not only the first person to climb all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks but also the first to do so without supplementary oxygen. His climbs on the world's highest mountains were usually either completed solo or in lightweight alpine style, often by new, challenging routes.

We asked one of our mountaineering experts to delve into the life of this legendary figure, detailing his journey to the top of the world’s highest mountains, the tragedies and successes along the way, and his legacy.

Growing up in the Dolomites

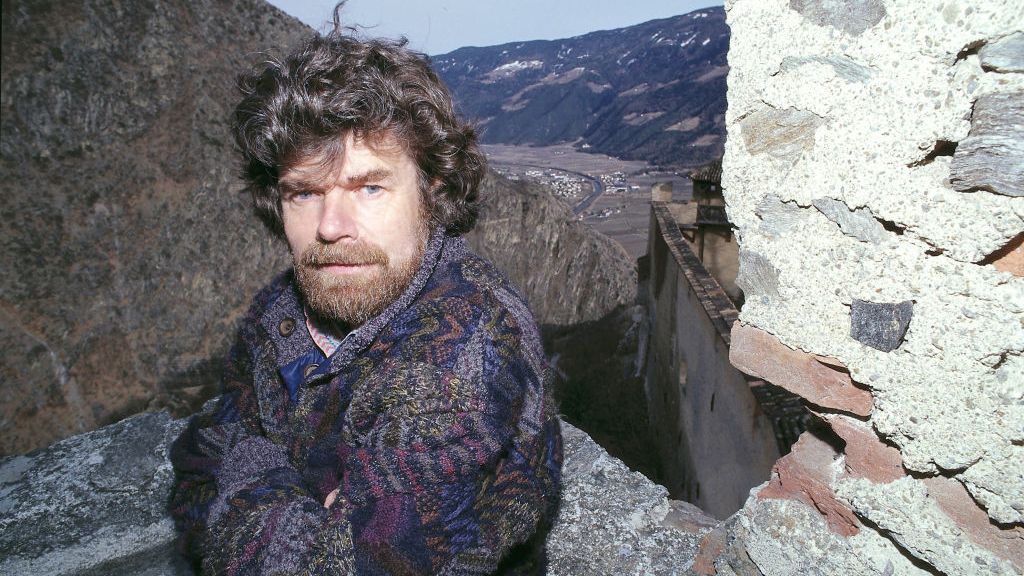

Messner was born in 1944 – during a Second World War air raid, no less – in the German speaking South Tyrol region of the Italian Dolomites. His father was an avid mountaineer and introduced him to the pursuit – Messner was up his first 3,000-meter peak, Saß Rigas, at the tender age of five. Growing up in South Tyrol, he had an almost unrivalled mountain playground on his doorstep and his climbing gained momentum from his early teens onwards, often alongside his brother Günther. Messner has always been enamored with his homeland, once famously saying: “Each mountain in the Dolomites is like a piece of art.”

He spent his youth developing climbing technique on the great walls of the Dolomites and in the Alps. In 1969, he stunned the mountaineering community with two remarkably bold solo climbs on technical rock and ice routes. First was La Civetta 's Philipp-Flamm dihedral in his Dolomite home, followed by the North Face of Les Droites on the Mont Blanc massif. This imposing north face had only been climbed three times previously and had taken at least three days on all previous occasions. Messner climbed it in eight-and-a-half hours.

Meet the expert

Nanga Parbat

Messner’s first 8,000-meter climb was tinged with tragedy and marred by controversy. In 1970, brothers Reinhold and Günther made the first ascent of Nanga Parbat’s hugely challenging Rupal Face, often referred to as the world’s highest big wall and one that remains a glittering prize even to this day. A direct climb of the face was achieved in 2005 by American great Steve House alongside Vince Anderson, very much a masterpiece of modern-day mountaineering.

Anyway, back to 1970. Having achieved a remarkable climb to the summit, Günther was in an exhausted state and suffering badly from the effects of altitude. Reinhold made the decision to descend the unknown but less technical Diamir Face, rather than return down the more difficult Rupal. Tragically, Günther perished in an avalanche during the descent and Reinhold barely made it out alive himself, losing seven toes to frostbite. He’d pulled off a staggering traverse of an 8,000-meter peak but at a huge personal cost. Plus, the loss of his toes put an end to his rock climbing career – henceforth, Messner would focus on high-altitude mountaineering.

Many questioned Messner’s role in the death of his brother, some accusing him of letting his own ambitions take precedence over the safety of a family member, who he was accused of abandoning during the climb. Messner has always refuted these claims, and his version of events was proven to be true by the discovery of Günther’s body, 35 years later.

By fair means – climbing 8,000ers without oxygen

Messner’s idol was the Austrian great Hermann Buhl who, in 1953, claimed the first ascent of Nanga Parbat, becoming the first person to summit an 8,000-meter peak solo. It was Buhl’s fast and light, alpinist style that he admired, an approach that Messner would swear by for his entire career. He was a vocal critic of siege style expedition tactics, even during the 1970s, and was totally against using supplementary oxygen to achieve any given summit.

Many considered such a feat impossible on mountains like Everest, where the scant levels of oxygen available in the atmosphere in the so-called ‘Death Zone’ above 8,000 meters made progress laboriously slow and potentially lethal. Where climbing Everest was concerned, Messner was quoted as saying he’d do it “by fair means” or not at all.

By 1978, Messner had already summited Nanga Parbat, Manaslu and Gasherbrum I without using oxygen. The 1975 ascent of Gasherbrum I, alongside Austrian legend Peter Habeler, was particularly notable for being the first ascent of an 8,000-meter peak using alpinist tactics rather than the traditional expedition approach. It took the pair just three days. The climb was light years ahead of what other mountaineers were achieving at the time.

Next on Messner and Habeler’s hit list was Everest, which they successfully climbed in 1978 and again, without supplementary oxygen. This proved to the world that such a climb was possible. Messner returned in 1980 and ascended via the northeast ridge and the previously unclimbed Norton Couloir. In doing so, he became the first person to climb Everest solo.

His adventures on the world’s 8,000-meter peaks continued until 1986, when he successfully summited Lhotse, becoming the first person in history to climb all 14 mountains. This would be the last time he stood on the summit of an 8,000er. During his 16-year odyssey, he’d proven that the world’s highest mountains could be climbed in an alpinist style, without oxygen, and often by new or partially new routes. It was this incredible period in his life that elevated his status from mountaineering great to legend.

Deserts and poles

After his mission to climb all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks, Messner turned his attention to more esoteric adventures, taking him to places as far flung as Bhutan, South Georgia, Pamir, Greenland, the Gobi Desert and Antarctica.

In 1990, alongside German explorer Arved Fuchs, he became the first person to traverse Antarctica via the South Pole on skis, with no mechanical or animal assistance. This remarkable journey took 92 days and the pair covered around 1,740 miles. They carried the first prototype of a GPS receiver, though it was neither particularly operational nor reliable back then.

His passion for challenging traverses reared its head again in 2004, when he took on a solo, 1,250-mile trek across Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. He achieved this traverse with no phone or satellite communicator, stating that it “wouldn’t have been an adventure anymore” to carry one. Messner’s attitude to what constitutes an adventure was summed up in an interview with Guardian in 2007, when he said: “For adventuring I have a simple ABC rule: no artificial oxygen, no bolts and no communication.”

Legacy

Messner has left an indelible mark on the mountaineering world, inspiring countless burgeoning alpinists to measure themselves against some of the toughest environments in the world.

He weighed in on the topic of the Seven Summits: the popular peak-bagging list that contains the highest peaks on each of the seven continents. He asserted that, rather than Australia’s Mount Kosciuszko (2,228 meters), Indonesia’s more technical and much higher Puncak Jaya (4,884 meters), also known as Carstensz Pyramid, should be included on the list. Today, it is the Messner List that is generally accepted. Though Messner has also been critical of the challenge, calling it a “childish game” that impresses the “media public”. He's similarly critical of what he sees as the rampant tourism of wealthy individuals paying to be guided up and down 8,000-meter peaks.

The Dolomites are home to no less than six Messner Mountain Museums, where visitors can learn about the region, the world’s mountains and mountaineering history in general. The first opened in a medieval castle in Juval in 1995 and the others soon followed. Themes of the individual museums include rock, ice, the mountain people of the world and the supreme discipline of mountaineering and the great walls. Messner has written extensively too, with over 80 titles published, many of which have been translated into English.

He's long been a champion of sustainability and the protection of the natural environmental. Between 1999 and 2004, he was an elected member of the European Parliament, representing the Italian Green Party. Along with Doug Scott, Chris Bonington and Patagonia’s Yvon Chouinard, he was a founding member of Mountain Wilderness, an international organization with a mission to preserve the world’s mountain regions’ natural beauty and cultural heritage.

In 2010, he was the recipient of the second ever Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award. The Piolets are generally regarded as the prestigious mountaineering equivalent of the Oscars.