Ilya Ponomarev was once a member of the Russian parliament, an unruly liberal tolerated by the leadership. These days, he’s on a mission to slay Vladimir Putin and his aides.

“They should be terminated with an aspen stake through their hearts,” he wrote in his memoir, Does Putin Have to Die?: The Story of How Russia Becomes a Democracy after Losing to Ukraine.

Exiled in Ukraine since 2016, Ponomarev is the political head of the Freedom of Russia Legion, a volunteer militia thought to include about 1,600 Russian dissidents and defectors using pinprick tactics to aggravate Russian troops with the aim of one day marching on Moscow.

To some, he cuts a maverick, temptingly plausible figure. The 48-year-old compares himself to Charles de Gaulle, the French military leader who led his nation’s resistance to the Nazis from exile during World War II and later became president.

Who is the man who has reportedly been giving Putin, the president who will run again next year, nightmares?

Who is Ponomarev?

A self-confessed “libertarian communist”, Ponomarev hails from an elite background, his mother having once sat in parliament, his grandfather a former Russian ambassador to Poland.

Born in Moscow, the physics graduate started out as a tech entrepreneur, transferring his skills to the oil and gas industry. In his 20s, he worked with Yukos Oil, then chaired by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the oligarch now exiled in London.

As he recounts in his book, he later worked with a TV company, almost striking a business deal with CNN that was scuppered by Putin. Such was his frustration that he decided to enter politics.

In 2007, at the age of 32, he entered the Duma, elected on the ticket of Just Russia, a social-democratic party within the Kremlin-approved “systemic opposition”.

Even so, Ponomarev stuck his neck out, invoking the “crooks and thieves” epithet for the ruling party that had earlier been popularised by Alexey Navalny, the opposition leader now behind bars.

In 2012, he and fellow party member Dmitry Gudkov played a prominent role in the “white ribbon” street protests against Putin, decrying the alleged rigging of the 2011 parliamentary and 2012 presidential elections. The following year, he refused to support a law banning “gay propaganda”.

However, Ponomarev definitively crossed the Rubicon when he voted against the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

He was captured on camera, refusing to stand and applaud when Putin referred to “national traitors” – a term used by Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf – in a key speech.

That image was printed on giant pro-government street banners that also featured Navalny; Boris Nemtsov, who would later be assassinated; and other dissidents with the words “Aliens among us” emblazoned below.

By 2016, he went into exile in Ukraine.

Since Russia’s invasion began in early 2022, he has positioned himself as the public face of pro-Ukraine Russians, speaking not only for the Freedom of Russia Legion (FRL) in Ukraine but also the National Republican Army (NRA), a secretive network of partisans allegedly operating within Russia.

Ponomarev also set up a wartime Russian-language opposition TV channel, calling it February Morning, in reference to when the war began. He used it as a platform to announce the NRA’s claim of responsibility for last year’s assassination of Darya Dugina, the daughter of one of Putin’s close political allies, on the outskirts of Moscow. US intelligence had blamed the car bombing on Ukrainian forces.

Still, within Russia, he remains relatively unknown.

“Average Russians don’t know much about what Ponomarev is doing right now because there is heavy propaganda, and it’s not within Putin’s interests to popularise or advertise him,” said Natia Seskuria, an associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based think tank.

What is the Freedom of Russia Legion?

The FRL is one of two Russian groups working within Ukraine to bring down Putin’s government. The other one being the Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC). While both share the same aim, they are ideologically different. The RVC is commanded by a known Nazi close to the local Azov regiment, an ultra-nationalist volunteer military unit.

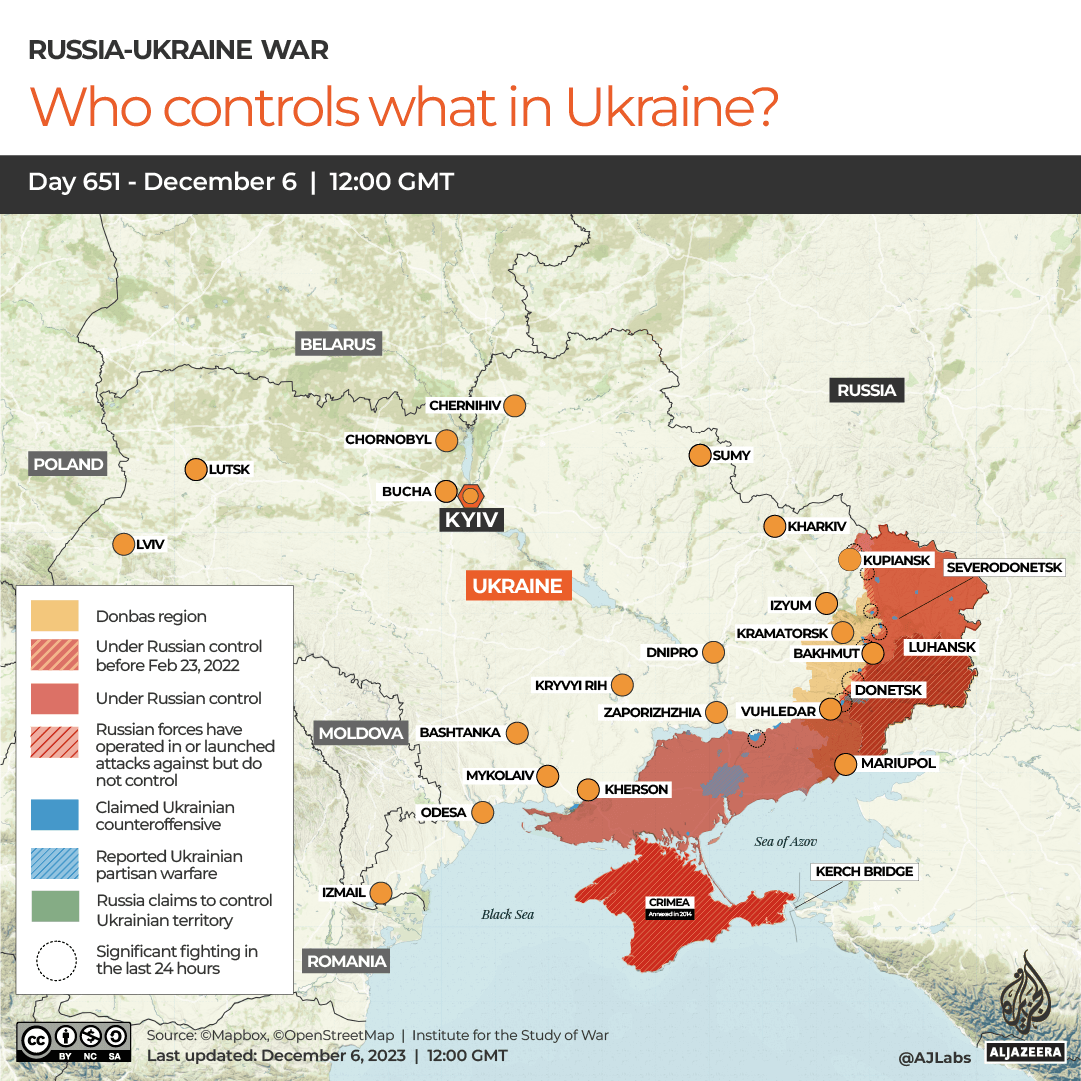

Last May, the FRL and the RVC shocked the world with their joint cross-border raids on western Russia’s Belgorod region. It was the first time that partisans had entered Russia during the Ukraine war. Footage of the attacks showed a Russian officer lying face down in a pool of blood next to Russian passports at a border checkpoint in the town of Grayvoron.

Ponomarev said Ukraine’s military intelligence is supporting his coup efforts.

This year, he claimed a role in a drone attack on the Kremlin, saying his group had helped to smuggle the devices over the border. He also has suggested he was involved in the assassinations of war blogger Vladlen Tatarsky and pro-Kremlin novelist Zakhar Prilepin.

But many treat his claims with scepticism.

“He’s got no kind of background in military or covert operations. He’s entirely dependent on the Ukrainians. Probably Ukraine’s quite happy for him to kind of try and claim credit,” said Roland Oliphant, senior foreign correspondent with The Telegraph who reported from Moscow for a decade.

The FRL is steered by the Congress of People’s Deputies, a shadow parliament of sorts that Ponomarev helped to set up. Based in Poland with members inside and outside Russia, it is hoping for Putin’s government to collapse and is working on a transition plan and new constitution.

Congress leaders include Mark Feygin, a former lawmaker and lawyer who represented the Pussy Riot feminist, anti-Putin punk band. But the body lacks big names, like Navalny and chess grandmaster-turned-political activist Garry Kasparov, who are not keen on the FRL’s violent tactics.

Should Putin be worried?

Ponomarev hopes to build a force that can march on Moscow. Could he succeed where Wagner Group chief Yevgeny Prigozhin failed?

The late Russian mercenary chief, who led the onslaught on Ukraine but fell out with Russian army leaders, staged a spectacular mutiny against the Kremlin in June, taking control of Russia’s military headquarters in Rostov-on-Don. He quickly called off the revolt, relocating to Belarus before dying in a mysterious plane crash two months later.

“The power of Prigozhin was that he had all these nationalist Russian credentials. He’d led a force in Ukraine. He was clearly pro-war. He was clearly not a national traitor. I think that’s quite important to Russians,” Oliphant said.

Stationed on enemy territory, Ponomarev has a bit of a PR problem.

As Oliphant pointed out, he lacks elite support to mount a coup, particularly within the security services.

“Are any of those guys in the FSB [Federal Security Service] and FSO [Federal Protective Service] and a whole string of other agencies going to do a coup on behalf of this self-proclaimed liberal who fled to Ukraine?”

According to Seskuria, the Kremlin has quickly buried memories of Prigozhin’s coup.

“A lot of things have changed, and the regime has become more ruthless,” she said. “The stakes are so high that I don’t really think Russians are ready now to speak out or go out onto the streets and protest.”

Now on Russia’s “terror” list, Ponomarev has turned himself into a highly visible target. But it doesn’t look like he’ll be sticking his “aspen stake” into the regime’s heart any time soon.

“Maybe he thinks that he’s going to ride into Moscow on the back of an American or Ukrainian tank,” Oliphant said. “I think that’s the only way he’d get there to be honest.”