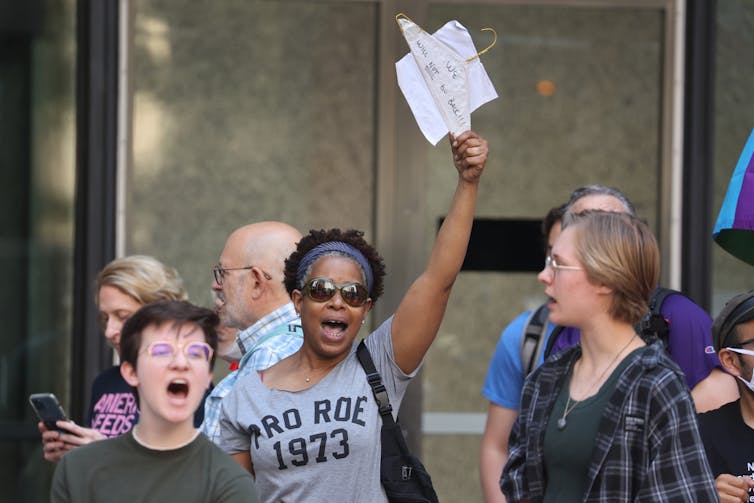

More than a year after the Supreme Court ended federal protection for abortion rights in the United States, disagreements over abortion bans continue to reverberate around the country. Candidates sparred over the idea of a federal abortion ban during the Aug. 23, 2023, Republican presidential debate. And abortion is likely to figure prominently in the November 2023 contest for a seat on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, removing women’s federal constitutional right to get abortions and giving states the power to pass laws about the legality of the procedure, the 6-3 vote was by a four white men, one Black man and a white woman majority.

Since that decision – Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization – more than 1,500 state legislators, who are overwhelmingly white men, have voted for full or partial abortion bans.

This is not the first period in U.S. history when white men have exercised control over women’s right to bear – or not bear – children, including during slavery. Then, it was a matter of numbers. The more people they enslaved, the more money white male enslavers could earn either from selling the enslaved or from the forced labor of the enslaved. White men controlled people’s reproductive rights during the 20th century, too, with the American eugenics movement.

From the late 1800s until the 2000s, white proponents of eugenics – the selective breeding of people – tried to determine who was fit or unfit to have children. While the American eugenics movement affected people of other races and ethnic backgrounds, as well as men, it was particularly harmful to Black women who, data from 1950 to 1966 shows, were sterilized at “three times the rate of white women and more than 12 times the rate of white men.”

During both periods, Black women and their health bore the brunt of the consequences of white men’s control.

As a researcher who specializes in the history of race and racism in the U.S., I study historical issues related to race, gender and social justice.

Enslaved women forced to reproduce

African midwives, imported and enslaved as early as the 1600s, attended to the birthing needs of the enslaved and enslavers until the beginning of the 19th century.

But, after 1808, enslavers in the United States could no longer legally import enslaved people. With this shift, enslavers stepped up the forced breeding of enslaved women. White men raped the Black women and girls they enslaved, and then enslaved the children born from those rapes. White men also forced the Black women and Black men they enslaved to have sex with one another to generate more babies, who would be born into slavery.

This was a systemic way of ensuring enslaved women bore more children, which would increase profits for their enslavers.

Because the Black midwives and enslaved women often were blamed for or suspected of using birth control and abortions to resist forced pregnancy and the enslavement of their offspring, enslavers turned increasingly away from midwives and to white male doctors to figure out why nearly half of enslaved infants were stillborn or died within their first year of life and why so many enslaved women were infertile. These doctors also helped with difficult births.

In the two decades after 1810, the population growth rate of the enslaved averaged about 30%, despite the ban on slave importation. This was just under the 1800 to 1809 average of 31.6% which was a century high.

In the 1800s, as the slave population increased, profits in cotton did too. And after the legal importation of slaves ended, the value of Black women of childbearing age increased significantly. The forced breeding of these enslaved women was linked to the profitability of southern economies.

Eugenics and control over women’s bodies

Eugenicists believed that increased breeding by white people, whom they assumed had high IQs, would benefit American society. But people who did not embody their idea of racial perfection, such as Black people, Native Americans, certain immigrants, poor white people and people with disabilities, should be sterilized – typically via tubal ligation and vasectomy.

In this debunked pseudo-science, eugenicists often used intelligence tests to determine who was fit or unfit to reproduce and to predict who would commit crimes, end up in poverty or have children who were mentally ill or intellectually disabled. And they worked to incorporate their ideas into state laws.

Thirty-two states, between 1907 and 1937, enacted forced sterilization mandates to prevent births by people eugenicists considered socially inadequate.

State-mandated procedures resulted in the coerced sterilization of women, particularly African American, Native American and Hispanic American women, and those from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Beginning in 1948 with President Harry Truman’s executive order to integrate the military, which extended to other areas, including education, employment and commerce, sterilization rates for Black women increased. For example, in North Carolina, which had the country’s third-highest sterilization rate, far more women than men were forcibly sterilized. And in the 1960s, Black women in the state made up 65% of the women sterilized, while only making up 25% of the population.

Between 1930 and 1970, close to 33% of the women in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, were forcibly sterilized. In California, between 1997 and 2003, 1,400 female inmates, mostly Black, were forcibly sterilized.

The post-Dobbs era

White nationalists and some right-wing politicians in the U.S. see the nation’s demographic changes as dangerous. The Census Bureau projects that in the 2040s, non-Hispanic white people will no longer make up a majority of the U.S. population. The nation’s racial and ethnic makeup will then be what some call “majority-minority.” Those projections scare racists, who believe in a conspiracy about white people being destroyed, which they label the great replacement theory because they fear losing social, political and economic power.

There is no way to know if this theory factored into the majority’s votes in the Dobbs decision, but the argument that not enough white people are being born has been a common historical thread in the American anti-abortion movement.

But, while believers in the great replacement conspiracy want white women to have more babies, actual anti-abortion decisions like the Dobbs ruling harm Black women more than any other group. Black women represent 39% of the country’s abortion patients, but many live in communities that have limited access to family planning clinics. And they have disproportionately higher rates of complications during pregnancy.

As a result, Black women – who experience higher maternal complications and mortality rates – will be forced to give birth to more babies.

This is another period in the country in which the reproductive health decisions made by mostly white men will harm Black women.

Rodney Coates does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.