“Working with John Lennon was the least painful thing I ever did in my life,” New York studio giant Gordon Edwards told Bass Player. “When you played with him, you could feel him listening to you. He didn't bother or bug you at all; he let you be yourself. He'd just sit down and we'd start playing.”

Edwards ranks highly among the unsung bass guitar heroes of the ’70s recording scene: bass players who operated largely under the showbiz radar but who nevertheless helped churn out hit after hit, all while quietly weaving their own low-end legacies into the fabric of music history.

In addition to his work with one half of the world's most famous songwriting team, Edwards’ discography also boasts collaborations with such artists as Paul Simon, Donny Hathaway, James Brown, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Aretha Franklin, Joe Cocker, Hall & Oates, Carly Simon, Grover Washington Jr., and Van McCoy (yep, that's Edwards laying it down on The Hustle).

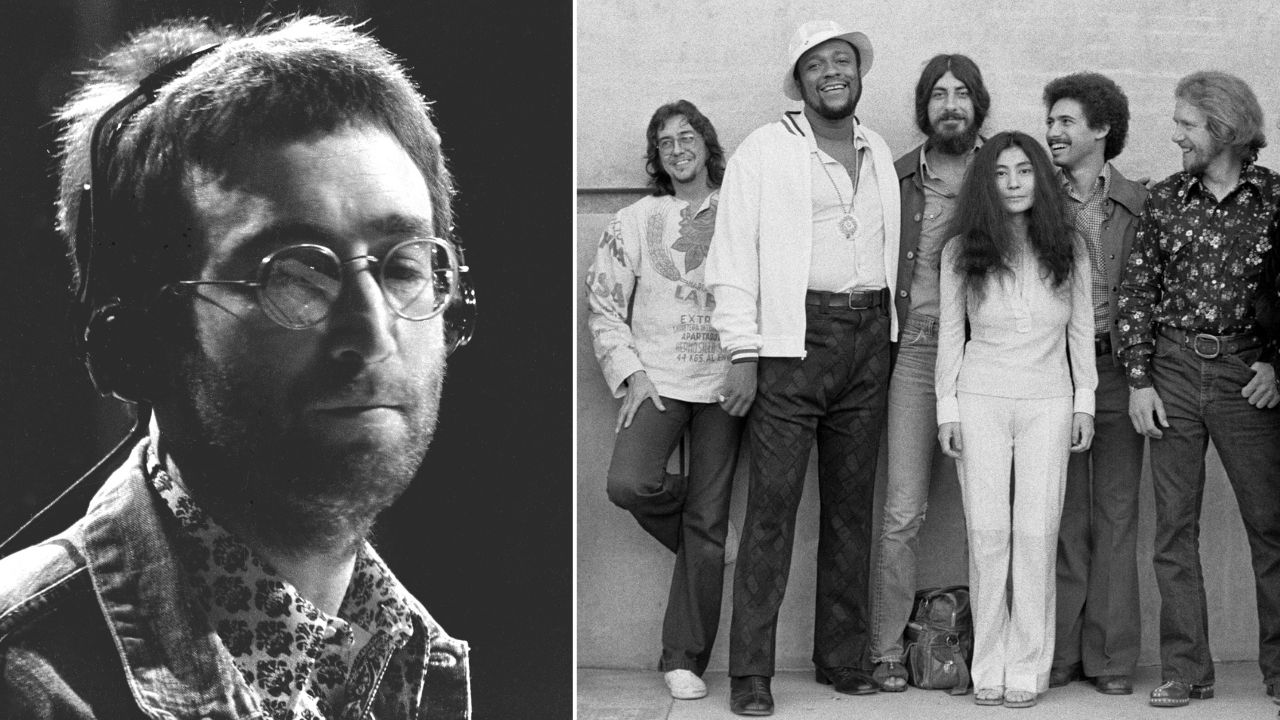

He was also a founding member of the pioneering R&B/funk unit Stuff, featuring A-list session buddies Cornell Dupree, Eric Gale, Steve Gadd, Chris Parker, and Richard Tee.

In 1973, when John Lennon began putting together his fourth post-Beatles album, Mind Games, Gordon's close connection with David Spinozza – Lennon's musical arranger – put him in the right place at the right time.

“For me, John just made it completely easy,” Gordon told Bass Player. “It was a perfect example of very cool songs written and played by an artist with the most tremendous feel.”

Mind Games opens with a moderately paced pop ballad bearing the same name, which has since become one of Lennon’s most popular songs. “David Spinozza knew the melody; he had that written out. But as for the arrangement, he left that to the musicians. Basically, all we had were the chord changes.

“I used a 1958 Fender Precision strung with La Bella medium gauge flatwounds, and we had one line going directly into the board as well as a mic’d amp for that external sound and feeling; I think it was a tube-type Ampeg B-15. The whole rhythm section tracked together, and I think they added a few parts later.”

The song kicks off with a four-bar phrase built on a series of simple chords that outline a descending C major scale. Edwards shadows this downward movement with sustained half-notes throughout the intro and first verse, offering little hint of the masterclass in space and pacing about to unfold.

In the next section, Edwards flouts convention by skipping the downbeat of each bar, while also leaving acres of room between his considered rhythmic comments. “I went into a reggae mood in the middle section; that was easy to do since I'm West Indian, anyhow. I like to make space for the melody to come through – I learned that from jazz bassist Leroy Vinnegar. He'd play melodies within his basslines, and he influenced me a lot.”

Reintroducing his downbeats in the second verse, Edwards returns to longer notes and begins mixing in chromatic connections between the primary tones. The first bar contains a particular treat as Edwards slips in a delightfully jarring B, on beat four as he moves from the Em/B chord on beat three to the Am7 downbeat, alluding to a Bb7 tritone substitution for E7.

Though the second verse is rooted firmly in C major (with a short nod to G major courtesy of the D7 chords), the bassline touches upon every note of the chromatic scale – atleast twice.

As the song heads toward the fadeout, Edwards again underlines his penchant for coloring the basic harmony through the use of the 5th, which he foregrounds heavily during the track's last seven bars.

Reflecting on his style in general, Edwards told Bass Player: “Some people like to solo, but I really enjoy laying a groove down; I used to loop before people even knew what looping was!

“When I do make a change it's because I'm going into the channel or something, and it's time for something new. But when I'm laying down a groove, there's no way you can stop me – even if you've got a pistol!”