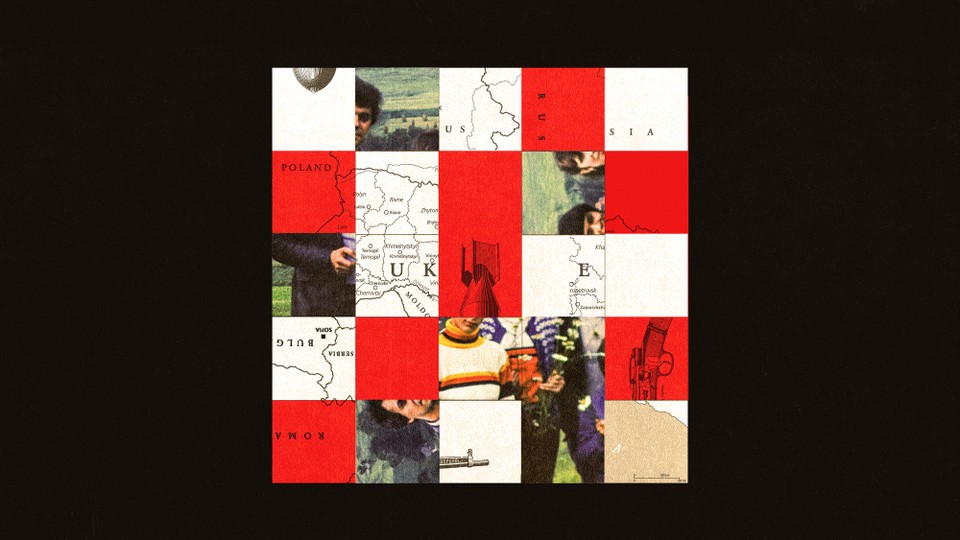

As I write these words, Russian bombs are pummeling homes across Ukraine. Men have been called upon to fight, women and children forced to flee. This war is not only separating families within Ukraine; it will harden the separation of many extended families living across the Russian-Ukrainian divide. Indeed, as I have learned from my own family’s experience, difficult choices will need to be made in order to survive, and the resulting pain and regret are likely to ensure that ruptures are never fully healed. I fear Ukrainians and Russians will find out—as many Chinese separated by the Taiwan Strait have—that long after the guns are silenced, even if the best efforts at reconciliation are undertaken, separation doesn’t end when the war does.

In 1949, the Chinese Civil War split China geographically and politically into the Communist-controlled mainland and the Nationalist-controlled Republic of China in Taiwan. The last battle of that four-year war was fought on a 60-square-mile island called Jinmen (otherwise known as Kinmen or Quemoy), just a mile off the coast of the mainland and 100 miles from the island of Taiwan, to which the Nationalists were retreating.

When the battle for Jinmen broke out, my aunt Jun—my mother’s half sister—was there, celebrating her college graduation with her best friend. After two days of fighting, the Nationalist army halted the Communists’ hitherto unstoppable advance. Then the ferries stopped, and Jun was stranded. Her family, her new job, and everything she’d ever owned were on the mainland. All she had with her was a small suitcase containing a few changes of summer clothes.

The Communist defeat at the Battle of Jinmen brought the Chinese Civil War to a stalemate, and Jinmen today remains the frontline defense of the Republic of China, in clear view of the People’s Republic of China on the mainland. Yet these two parties—the Nationalists and the Communists—emerged from the same cultural, historical, and linguistic background, and immediately after the stalemate set in, they each launched multipronged campaigns to establish their mandate as the sole legitimate government over all of China.

The Nationalists, or KMT, published maps with added narratives highlighting a direct historical path from the last Chinese dynasty to the establishment of the Republic of China, and to President Chiang Kai-Shek’s leadership. National treasures that had been shipped from Beijing to Taiwan were enshrined in a newly constructed museum in the outskirts of Taipei; the slogan of “Recover the mainland!” was promulgated, and Mao Zedong was branded “Mao the Bandit.”

The Chinese Communist Party was no different. It instituted a series of state-building campaigns, many anchored to the idea that Chiang was a “counterrevolutionary” leader on the run, and that his accomplices needed to be swept up and punished. Thus, anyone with even remote ties to, or even the vaguest sympathy for, the Nationalists would be persecuted. I was raised in Fuzhou, a short distance from Jinmen, and my generation grew up with mantras such as “Only the CCP can save China” and “We must liberate Taiwan,” in which the We referred to Chinese people on the mainland.

After Jinmen was sealed off as a Nationalist military base, Aunt Jun became a journalist. Two years later, in 1951, when Chiang’s wife visited Jinmen to boost the morale of the KMT military forces there, Jun wrote a laudatory report on the trip. With her writings now out in full public view, and her position clearly aligned with the KMT, Jun became a tremendous political liability—even a life-and-death one—for all her relatives in CCP-controlled China.

On the mainland at this time, waves of revolution aimed to root out the feudal past, cleanse KMT remnants, and build complete loyalty to the CCP. To survive, our family had to erase Jun from the family narrative. As a result, an entire new generation—my generation—would come of age not knowing that we had an additional aunt at all.

Aunt Jun, meanwhile, moved from Jinmen to Taipei and established a successful business. But her dream to reunite with her family never died. In 1982, after the United States switched its diplomatic recognition from the Nationalist government in Taipei to the Communist government in Beijing, and travel to mainland China became much easier from America, Jun—who by then had immigrated to the U.S.—finally reunited with her mainland family, after 33 years of separation.

For me, her timing was perfect. This aunt who I had not known existed stepped into my life at the very moment when my government employer refused to let me apply to graduate school. Jun sponsored me to study in America, and she did not stop there. She sponsored my cousin too. She even bought her older brother, my uncle, his first apartment, in a new high-rise in Fuzhou. She single-handedly pushed our family into the modern era, at a time when the majority of those around us had not even started to dream of such miracles.

Yet true reconciliation proved difficult. Jun had gone back to the mainland to rekindle shared family memories of a prerevolutionary past. Her mainland relatives, however, weren’t interested in rehashing a past that included Jun, one that had contributed to their suffering during Mao’s revolutions. For Jun, though, her being stranded on the wrong side of the Taiwan Strait hadn’t been a matter of choice, but a random circumstance of fate.

Before Aunt Jun showed up in my life, my family’s narrative, riddled as it was with holes, was my entire world. But from Aunt Jun, I would learn of more and much larger missing pieces, including the family’s hundreds of years of illustrious history, one of ministers and an emperor’s tutor. After moving to America, I learned to ask questions about this family history. Asking questions had been discouraged and suppressed on the mainland: Only the authorities asked questions, not ordinary people. With this newly acquired skill, I came to see things that had been in plain sight all along. The Battle of Jinmen, for example, was never taught in schools or discussed in books on the mainland, part of the willful national amnesia imposed on us all, one that parallels my family’s decision to disappear Aunt Jun.

Living in America helped me see the two sides of my family for the whole that they comprised. Jun never experienced that same revelation. She and her mainland family had lived in, and in many ways been confined to, their different worlds after the sudden rupture, and they never had a chance to see and understand each other’s world as I did.

Jun continued to try to fix every broken strand to the past with her utmost effort, at times risking her own financial peril. At one point, she even planned to add herself and her husband to our family’s burial plot in Fuzhou so that she would be next to her parents for eternity. In those early years after she first reunited with us, she would remind me of the Chinese saying “Leaves fall to the root of the tree.” But decades later, after her husband’s death in Taiwan, she finally accepted the futility of that plan. She explained to me then that she had realized that neither her children nor those who had attended her husband’s memorial service in Taipei—political, military, and social luminaries among them—would go to Fuzhou to pay their respects anytime in the foreseeable future. She was 86 then, and it would turn out to be her last trip to Fuzhou. Aunt Jun’s moment of revelation had come at the very end of her life, and she accepted it reluctantly and with great sadness. Her life had been built after the separation from her family, in Taiwan and America, worlds to which her mainland relatives had no emotional or cultural connection.

Many families have been separated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Each of them will have a story to tell. Indeed, each division of any single family’s story will be unique, with its own holes and erasures. That’s the invariable result of the compromises people have to make in order to survive and continue capturing life’s potential. Still, these stories will take on trajectories of their own as they’re told for generations to come. And, one day, someone in the family might find a way to piece all these incomplete stories back together again.

Sixty years after Aunt Jun’s fateful trip to Jinmen, I finally visited the island for the first time, as an American citizen. As a child, I had learned to swim just across the water on the mainland, but had known of Jinmen only as an “enemy island,” an unimaginable place to visit. Now, standing on Jinmen, I could see the apartment high-rises on the distant mainland shore where my parents lived. At the water’s edge, I was finally able to put my family’s stories—all of our stories—together like a palimpsest, each imperfect in its own way, but layered together, feeling complete.