“We did fix ourselves in a good place in modern music,” reflects Eric Stewart. “I think we carried the mantle of The Beatles in that everything we wrote, recorded and released – whether it was a single or an album – was completely different each time we went in the studio. We didn’t have a George Martin around to keep us in check though, and the amazingly different ideas that we kept coming up with – musically, lyrically etc – would sadly eventually tear us apart.”

As four gifted musicians who were all accomplished songwriters, 10cc should have been the next Beatles. They had the brains. They had the balls. They even had the Gizmotron. And in Eric Stewart they had a savvy businessman: Having made some money as lead singer and guitarist with The Mindbenders, Stewart had the foresight to partner with Peter Tattersall (former road manager for Billy J Kramer) and invest his savings in a studio in Stockport – a professional studio outside of London, to cater for the ever-expanding music industry in and around Manchester.

Stewart, like Tattersall, had always harboured an abiding interest in the engineering and production side of making music, and it was Stewart who dubbed it Strawberry Studios after John Lennon’s own homage, Strawberry Fields. A few months later, Graham Gouldman joined the partnership, investing earnings he had made from his success as a songwriter penning hits for the likes of The Yardbirds, Herman’s Hermits, The Hollies and Jeff Beck.

It was Graham who introduced Stewart to Kevin Godley and his art school friend Lol Creme. “When we were 14 or 15 years old," says Creme, "Kev and I wanted to be Simon & Garfunkel, we loved all those harmonies and wanted to write cool songs. The music and the lyrics were very important to us. And we were tuned in to the same wavelength: we were two halves of the same person. We could finish off each other’s sentences.”

Gouldman, meantime, departed for New York to work for the inappropriately named Super K Productions under Jerry Kasenetz and Jeff Katz, writing bubblegum pop songs for the likes of Ohio Express and Crazy Elephant. Gouldman felt his career had reached a low ebb, but he was able to sweet-talk his employers into allowing him to record some of his material at Strawberry Studios.

As the in-house band, the quartet were handsomely paid to grind out a ragbag of assorted songs that Super K Productions would issue Stateside under any number of trite pseudonyms. Of all the material they recorded over three months, it was the darkling humour of There Ain’t No Umbopo, a Wild Man of Borneo scenario dreamt up by Godley and Creme, which gave a tantalising glimpse through the foliage of things to come.

With the money they upgraded Strawberry Studios, installing an Ampex four-track machine and purpose-built control desk. While Godley spent hours behind his drum kit for a test recording, Lol Creme relieved the boredom by strumming his acoustic guitar and ad-libbing a primal lyric that became Neanderthal Man. Released as a single in June 1970, it proved a runaway success for Hotlegs, as the three-piece now called themselves.

The single sold over two million copies worldwide, but the failure of the group to tour and capitalise on their success meant the public soon lost interest in what appeared to be nothing more than a novelty act. The belated release of their album Thinks: School Stinks nine months later meant they had lost all impetus and so returned to working as the in-house band for many of the acts that hired the studio.

Neil Sedaka was another happy client of theirs. Solitaire, the album that saw Sedaka return to the charts after several years on the chicken-in-a‑basket circuit was recorded in Strawberry with the four men as his backing band.

It was time to form a band on their own terms. Gouldman recalls: “We began discussing the idea of doing something for ourselves. We were studio animals after all, so why don’t we form a band? It was a no-brainer, and we should have done it before.”

So the quartet began writing their own material, coming up almost instantly with the doo-wop parody Donna. Invited to listen to their demo, Jonathan King immediately signed them to his own UK label and gave them the name 10cc. Whatever his many faults, he ensured they had a Top 10 hit.

“I suppose we have to give him a certain bit of credit,” says Gouldman, “because he did it. He took the songs we had recorded and chose the best and gave us a hit single. Unfortunately, we signed away those songs for perpetuity: he was out to make money first and foremost. But everybody who was involved with 10cc in any way was a part of what we became, and we are proud of what we achieved.”

They were on a streak. Even though a second doo-wop skit, Johnny Don’t Do It, failed to chart, a string of exemplary singles followed in quick succession: Rubber Bullets, The Dean And I, The Worst Band In The World, The Wall Street Shuffle and Silly Love, each veering between art rock, musical cartoonery and high‑camp nonchalance.

With no preconceived ideas, their self-titled debut was recorded in three weeks. “The first album was 100 per cent instinct,” says Godley. “It was written and recorded very quickly in response to our first hit Donna. Prior to that, writing and recording was relatively formal and thoughtful, but this was about slapping ideas down as soon as they arrived and moving on.”

Gouldman also remains attached to the album. “The Hospital Song is one of my favourites. [Sings:] ‘I’ll wreak my wrath on all blood donors, and their sisters, visiting time and flowers, when sister brings that bedpan round I’ll piss like April showers.’ Lol really sings that last line with powerful gusto.”

The album also introduced the unsuspecting world to the Gizmotron, an effects device that had first been developed by Godley and Creme three years earlier. Mounted to the bridge of a guitar, the motor-driven device employed a series of serrated plastic wheels to vibrate the guitar strings and so duplicate the string section of an orchestra and various electronic effects otherwise difficult or time‑consuming to replicate. As a prototype synthesiser, it was a brilliant concept, even if annoyingly unreliable.

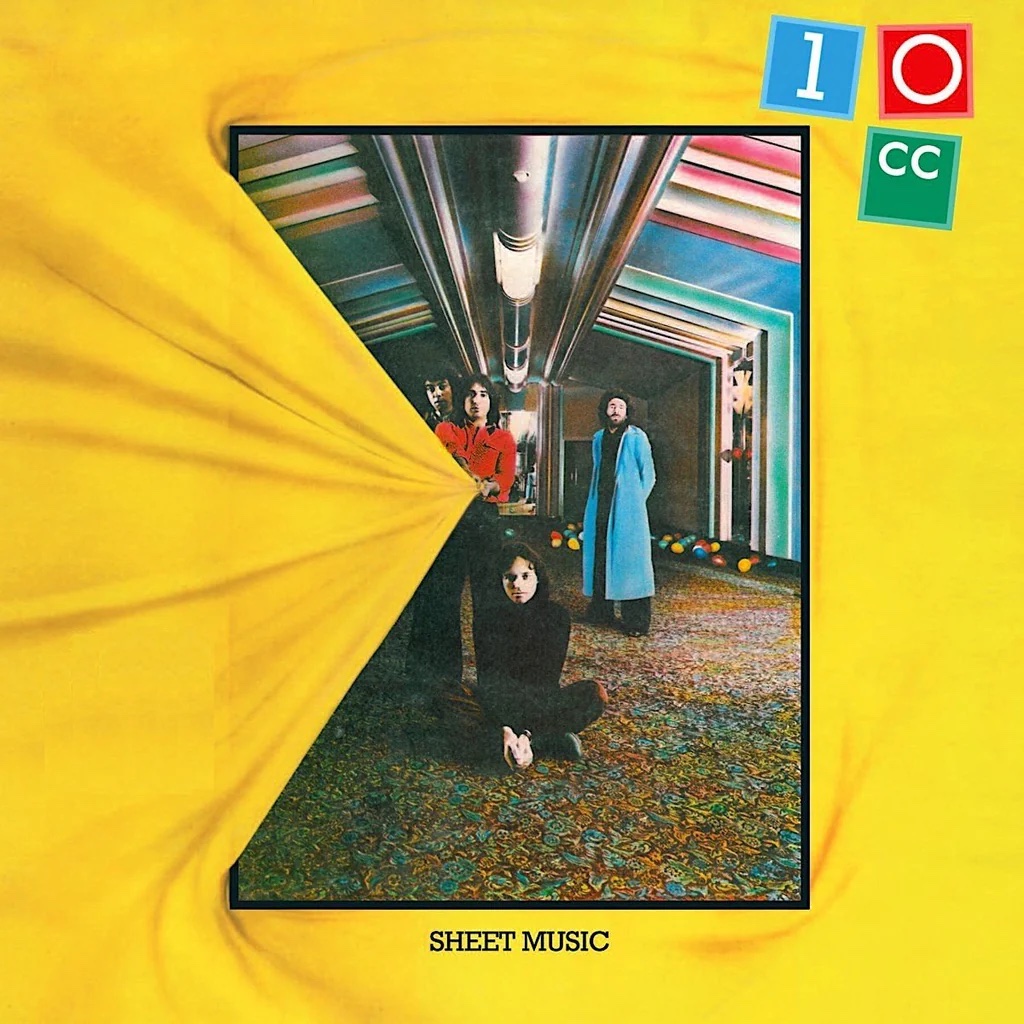

Their not-so difficult second album followed a short 10 months later. It wasn’t so much a hop, skip and jump as a quantum leap from their debut to Sheet Music. It was the flawless work of four individuals willing to collaborate on a first-hand job of work and who didn’t give a wang, dang doodle about what people thought or expected of them.

Stewart says, “Sheet Music was a thrill for us to record. We’d just scored several hit singles and our first No.1 with Rubber Bullets, and we were really flying high on those successes. We realised that, like The Beatles, we could record anything, in any style, and people would be interested.”

Sheet Music enshrined a rare moment when the whole band were singing from the same hymn book in the same church. It's Gouldman's favourite 10cc album. "I love the others but this one has the edge," he told Classic Rock. "The band was in a very good place. We were coming off the back of two hit singles, Donna and Rubber Bullets, but we’d had to rush to get that first album [10cc] out. With Sheet Music we could take our time, and that came across in the end result."

They worked during the day at Strawberry Studios and at night and Paul McCartney and his brother, Mike McGear, recorded Mike’s first solo album. "That added a certain frisson," says Gouldman. "I think we played Paul a few songs. He was very positive about them, but then he is a very positive bloke."

The pasta-based rationale of Life Is A Minestrone gave the band another hit when released as a trailer for their next album, The Original Soundtrack. This was a movie for the ears – scenes from everyday life shot in glorious technicolour, with the band seeking to embrace an ever more cinematic soundstage. From the mock opera of One Night In Paris to the ethereal melancholia of I’m Not In Love to their Fellini folly, The Film Of My Love, there’s much to savour here, even if the album ultimately suffers by comparison to Sheet Music.

Even the success of hit single I’m Not In Love did nothing to improve their image. As Gouldman explains: “Whenever they make documentaries about the 70s, people talk about glam rock and prog rock. I don’t tend to put 10cc in either category, but it still pisses us all off that we don’t get a mention.

“I know we didn’t have a frontman as such; Roxy had Bryan Ferry and Queen had Freddie Mercury and so on, and I know it didn’t help that we couldn’t project ourselves. We just didn’t have outgoing personalities. We were always known as the professors of pop, which I didn’t mind to some extent. But people often thought that we were more interested in the science of music, rather than the emotional side. But I don’t think you can get any more emotional than I’m Not In Love.”

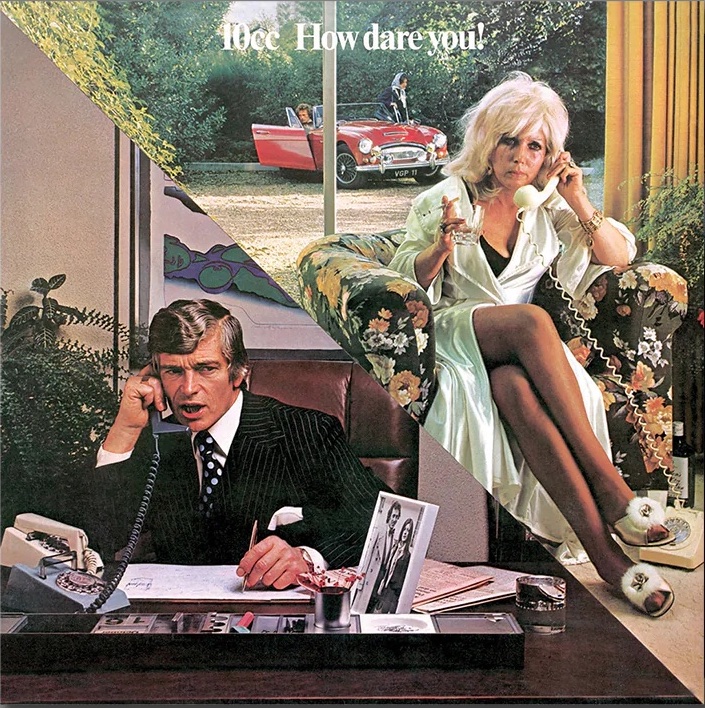

How Dare You! (1976) proved a more cohesive work than its predecessor, much of the album forsaking immediacy in favour of more thoughtful constructs. Communication is the problem to be answered here. It begins with the implied obscenities of the title track and concludes in the unspoken farewells of Don’t Hang Up, which signalled the end of the quartet’s marriage.

“We had a different approach to that album,” says Gouldman. “I sensed the beginning of the end. I remember while we were making it that we all got the vibe that the inevitable was going to happen and it did. But the flame burnt very brightly while it lasted.”

Stewart was also aware of the mounting tension. “How Dare You! was recorded as the two main writing teams – myself and Gouldman, Godley and Creme – really started to push in opposite directions,” he explains. “But it all seemed to work at the time and I really did enjoy engineering and mixing the album. While we were recording it, Kevin was coming out with some heavy statements like, ‘I don’t want to do any more crap like this,’ after I played The Things We Do For Love to him and Lol, but we somehow managed to get enough songs together to release an album.”

The story behind the hit I'm Mandy Fly me, illustrates the tensions perfectly: both Stewart and Goudman claim to have seen the poster that was the song's inspiration. The two couldn't agree on the early arrangements. Gouldman was disappointed in the lyrics, Stewart was disappointed with the music. Kevin Godley save the day.

Stewart: “The song wasn’t really knocking us out. Then, in his usual subtle way, Kevin said: ‘It’s too safe. It needs a kick up the arse.’ And he was right. It was well played and smooth but it didn’t make you sit up and take notice.”

It went to no.6 in the charts. Gouldman says that maybe it's the best representation of the original 10cc line-up: “Our three number ones were Rubber Bullets, which was a real rock song, sung by Lol Creme, the ballad I’m Not In Love, which Eric Stewart sang, and Dreadlock Holiday, a cod-reggae song sung by me. That’s almost three different bands. I’m Mandy Fly Me has all these disparate elements flying all over the place but they’re all distilled into one fantastic record.”

Kevin Godly and Lol Creme upped sticks and left to record an album of their own, primarily to promote the Gizmotron, Godley later claiming that “10cc was becoming safe and predictable”.

Gouldman and Stewart continued as 10cc until 1983. The hits kept on coming: Things We Do For Love, Good Morning Judge and Dreadlock Holiday, their final top 10 hit. But that's another story. There was a reunion of sorts on 1992’s ...Meanwhile album, and three years later, Gouldman and Stewart wound up the band after the poorly-received Mirror Mirror album.

Gouldman continues to tour with his own line-up of 10cc. The songs the original four made together still pull crowds and are still played on radio stations across the world

“We could just go into the studio and record with confidence because we were so well-rated that we thought people would dig it – and they did," says Creme. "And we were utterly grateful for the opportunity to do what we wanted.

"I don’t think any of us would have any complaints about that. We were the luckiest bastards on the planet.”