For K. Devi, a mother of three, immense relief came from unexpected quarters a couple of weeks ago. Her children go to the Government Primary School at Kondathe, a tiny, largely tribal, hamlet in the Jawadhu Hills of Tiruvannamalai district. The news that the school would give her children not only lunch but also breakfast came as a pleasant surprise to Ms. Devi. It took a whole load off her rushed mornings, when she and her husband, both farmworkers, leave home early. That the school would take care of her children and spare her the trouble of giving the children something to eat, no doubt, brought her much joy. “Earlier, we sent our children to school because at least they can have a good lunch there. Now, they get breakfast, too. We are happy,” she says.

P. Palani, headmaster of the school which her children attend, is also a relieved man. “Earlier the children, particularly the 13 children in the primary sections, would complain that they were hungry or cry out of hunger or just doze off during class. Now, no one complains! In fact, they are coming to school early so that they would be in time for the breakfast,” he says.

For both Ms. Devi and Mr. Palani, the satisfaction stems from the free breakfast scheme, which was introduced by the Tamil Nadu government in 2022 at select schools and which has been extended about a year later to all primary schools in the State. Tamil Nadu is the first State to launch a free breakfast scheme for students of government primary schools, a massive public venture. In the first phase, the government inaugurated the Chief Minister’s Breakfast Scheme at 1,545 primary schools run by the government, covering 1.14 lakh children of Classes I-V. On August 15 this year, the scheme was extended to all primary schools to benefit about 17 lakh students at 31,008 schools. The budgetary allocation is ₹500-odd crore every year.

The project reportedly benefits from the personal attention of Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, who follows in the footsteps of his predecessors. Tamil Nadu leaders have always laid stress on feeding students, ensuring they are able to study on a full stomach. Devised as a strategy to bring children to school, the programme also serves the twin goals of keeping children hunger-free, at a relatively low cost, and ensuring that they get adequate nutrition.

It was in 1920 that the first government scheme to provide free food, at the cost of one anna per student, was implemented. For two years, it was stopped after the British government disallowed the drawal from the Education Fund. But it revived subsequently. However, the two more prominent personalities with whom the concept of free school meal has irrevocably been linked are K. Kamaraj of the Congress, who introduced the scheme at schools in the 1950s, and M.G. Ramachandran of the AIADMK, who extended its reach in 1982. It was a flagship scheme for late Chief Ministers M. Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa too, and innovations, additions and modifications to the menu were regular, even if not constant.

Successive governments have responded well to the scientific imperative, and the social duty of preventing hunger among children, with the noon-meal scheme. The breakfast scheme crosses a further milestone. Nutritionists consider breakfast to be the prime meal of the day, the most important one, because it allows the body to be replenished with glucose and nutrients in order to have an active day. The menu provided at schools includes rice, wheat and vermicelli upma, pongal, kitchadi, with vegetable sambhar, and sweet pongal and kesari.

How it began

The government started with a scientific baseline study, conducted among older children (9-12 years) though, working on the assumption that their younger brothers or sisters may be in the same situation. While 57% of the children said they ate breakfast at home daily, about 43% said they did not eat breakfast at all, or had it occasionally, with 17% saying they never ate breakfast, says K. Elambahavath, project co-ordinator for the scheme. The government intervention would definitely be a welcome measure and not in excess, the baseline study proved, he adds.

In an interesting but understandable co-incidence, the figure of 43% (of children not eating breakfast daily) is the same as the percentage of families in which the mother was working. Clearly, the role of the mother is crucial in taking care of the breakfast of children. “A number of children come from homes where their parents are sanitary workers or construction workers, even agricultural labourers. They will have to leave home early for work,” Mr. Elambhavath says. In these cases, unless there is an older child or grandparent at home who can cook, the children often go hungry, but are sent to school to keep them from mischief.

There is a solid body of research that emphasises the multiple benefits of a good breakfast. While the health benefits, in terms of measurable factors — reduction in stunting and underweight — will take time to establish, the attendance records tell another tale. It warms the cockles of the heart but also provides resounding proof of the instant benefits of this intervention: improvement in attendance and enrolment.

Out of 1,543 schools in which the breakfast scheme was rolled out, 1,319 schools reported increased attendance in Classes I-V in January-February, 2023, compared with June-July, 2022, a study showed. That is over 85%. The attendance improved by from 10%-50%. In four districts, all the schools where the scheme was rolled out have shown an increased attendance percentage.

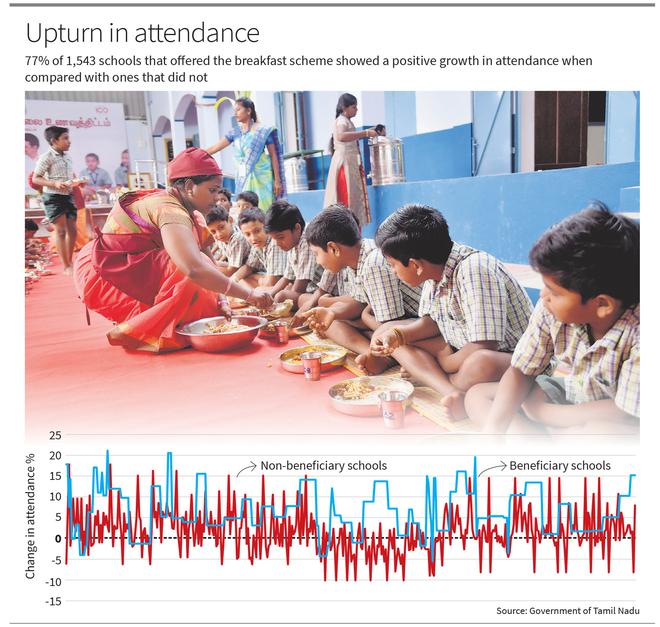

Mr. Elambahavath says the State Planning Commission did an analysis of nearby schools to measure attendance, in comparison with the schools where there was intervention, to examine if any other factor was contributing to the increased attendance. But it emerged that with all other factors remaining constant, it was the breakfast scheme that was bringing the children to schools. 77% of the beneficiary schools showed a positive trend in attendance, compared with their neighbouring schools.

A section of government school heads says enrolment has doubled since the scheme was introduced. “With the implementation of the breakfast scheme, the school, which caters to the underprivileged children in the locality, has attracted new students and improved the attendance of the existing students,” said H. Pushpalatha, headmistress of Corporation Elementary School, Edamalaipatti Pudur, Tiruchi.

“The breakfast scheme is of great help to parents who are daily-wage workers. This will also help their children perform well. More students will be interested in enrolling in schools, just the way it was during the implementation of the mid-day meal scheme,” says S. Sivakumar, retired principal, District Institute of Education and Training, Kancheepuram.

K. Bala Shanmugam, district secretary, Tamil Nadu Elementary School Teachers’ Federation, Nagapattinam, however, brought up the way in which the schools’ ecosystem has since adapted itself. “Usually, the self-help group workers leave the school around 9 a.m. But there are instances in which students come to school around 9.20 a.m. To tackle this, the respective school teachers are taking turns voluntarily to reach school early to serve breakfast to the students.”

P.A. Syed Sulaiman, monitoring officer for the scheme in the Jawadhu Hills, claims that in this area, more than 90% of the schools that have had the scheme since last year have recorded 100% attendance, no easy task in the hilly tribal hamlets.

Why self-help groups?

In Pudukottai last week, anganwadi and nutritious noon-meal workers staged a demonstration demanding that the government execute the scheme through their department. “Instead of engaging self-help groups for the scheme to cook the food, it should be implemented through anganwadi and noon-meal workers,” insists P. Anbu, district president, Tamil Nadu Nutritious Meal Workers Association. But the reason for the government to appoint SHG members is different. S.J. Chiru, Secretary, Social Welfare Department, says the aim is to employ SHG members whose children are studying in the school, so that they will ensure that the quality of the food remains good, instituting a fail-safe internal check and balance. Tirunelveli Collector K.P. Karthikeyan explains, “We’ve identified the mothers of the children who are active in the local self-help group. Since their children also eat breakfast every day, they will prepare the food with utmost care and ensure it’s tasty. Once these children pass out of the primary section, a new set of women will be roped in for preparing the breakfast.”

Mr. Chiru adds that the response to the scheme has been, in general, very positive. “What is really significant in this roll-out is the use of technology to monitor what is happening at every point of time. This leveraging of technology for monitoring the progress of a scheme is something that we do not have even for the noon-meal scheme yet, and it plays a role in ensuring that we are on top of the game at every stage.”

To monitor the effective implementation of the scheme, the Tamil Nadu e-Governance Agency introduced ‘CM BFS’, a mobile application. Three levels of staff undertake the data entry at every stage, uploading data and pictures, making it possible for a centralised control to be aware of the timelines and issues at every centre serving food and be able to address them easily too.

A teacher in a Salem city school confirms that every day, the preparation of breakfast is photographed and uploaded on the app. The school headmaster and management committee members will taste the food to ensure the quality before it is served to the students. In the first few days, the parents also checked the breakfast, and were happy with the quality, she adds.

What more can be done?

Though the scheme has been expanded to nearly 31,008 schools, the government-aided schools are kept out. Mr. Bala Shanmugham pointed out that at a few places, the parents of aided school students demand the breakfast be served to their children too, since the noon-meal scheme covers aided schools. S. Mayil, general secretary, Tamil Nadu Primary School Teachers’ Federation, says the students of aided schools also come from a similar economic background, and they should also be served breakfast at school.

The State would also do well to prevent caste pride from frustrating a well-conceived project in some areas. Parents of students of Kalingarayanpalayam Panchayat Union Primary School in Tiruppur district recently opposed the food prepared by a Scheduled Caste woman under the scheme and asked for transfer certificates for their children. Such incidents, though infrequent, have been reported even at noon-meal centres, but it is important that the government not allow such issues to affect the scheme.

Any programme that costs, thanks to economies of scale, a mere ₹12.71 per child per meal per day to boost the health of children is worth its weight in gold, as a public health intervention. Well begun is half done, so the government must stay on this project, keeping it in mission mode, to ensure its ideals are fulfilled and children are on the fast track to getting better nutrition and consequently, a brighter future.

(With inputs from D. Madhavan in Tiruvannamalai; Sai Charan and Ancy Donal Madonna in Tiruchi; P. Sudhakar in Tirunelveli; Aishwaryaa R. in Coimbatore; and M. Sabari in Salem)