The Liberal Party’s recently published review of the 2022 federal election defeat does not mince words: the party has a problem with women.

The party has struggled to connect with women voters in recent elections, especially from the 18-34 age group. Moreover, just nine of the party’s 42 MPs in the House of Representatives and ten of its 26 senators are women. There have not been so few Liberal women elected to parliament since 1993.

And this is at a time when, overall, there are more women in parliament than ever.

To address the issue, the Liberals’ election review says the party must begin “broadening the membership base with young women, and retaining them”. Doing so, the authors argue, will help to “ensure there is a much larger number of high-quality female candidates” in future elections.

According to our research on the youth wings of political parties in Australia, Italy and Spain, however, this will be no easy task.

Moreover, it is not just the Liberal Party that has a problem attracting young women to its ranks, but also Labor. Our study indicates that both of their youth wings, the Young Liberals and Young Labor, have far fewer women members than men. In addition, the proportion of women members in both youth wings who would like to stand as candidates is far lower than that of men.

What our research looked at

Our findings are based on surveys we conducted of six youth wings – three from the centre-left (Young Labor in Australia, Young Democrats in Italy, Socialist Youth in Spain) and three from the centre-right (Young Liberals in Australia, Forza Italia Youth in Italy, New Generations in Spain).

Youth wings are a key part of the political career pipeline in parliamentary democracies like Australia. Take New South Wales, for example. John Howard and Gladys Berejiklian were former presidents of the NSW Young Liberals, while Paul Keating and Anthony Albanese were former presidents of NSW Young Labor.

Several recent prime ministers and government ministers in Italy and Spain have similar political backgrounds.

In total, we surveyed almost 2,000 youth wing members in the three countries, with around 750 respondents from Australia. Ours is the first published academic study of youth wing members in this country.

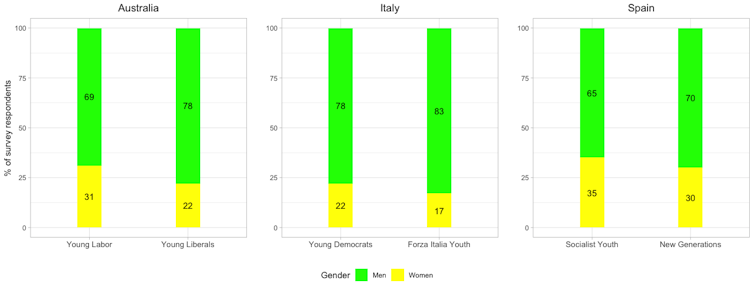

As the figure below shows, men far outnumber women among our respondents in all six youth wings. This is markedly the case in the two Australian organisations, with women accounting for less than a quarter of the Young Liberals respondents and less than a third of Young Labor ones.

The major Australian parties have long been reluctant to release reliable data about their organisations, so we do not know for certain if our respondents perfectly mirror the full youth wing memberships. However, our results certainly suggest that if the Liberals want to achieve gender parity among their younger members, they have a long way to go.

Fewer young women wanting to stand for election

What about the desire to stand for election? To understand the electoral ambitions of youth wing members, we asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “In the future, I would like to stand as a candidate for the senior party.”

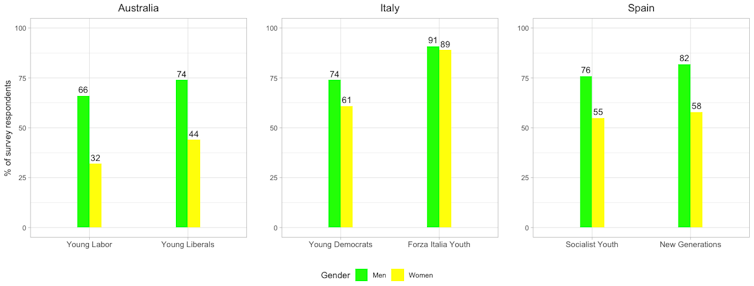

Here, the largest gender gaps are in Australia.

As we can see from the figure below, two-thirds of men in Young Labor say they would like to run for public office one day, but only one-third of women agree. We see a similar 30-point gap in the Young Liberals, with almost three-quarters of men expressing a desire to stand and less than half of women saying likewise.

Surprisingly, despite Labor’s implementation of candidate gender quotas - which have facilitated the election of 36 women MPs (out of the party’s 77 total) in the current house - Young Labor women were the least likely of all women in our survey to express a desire to stand for election. They are over ten percentage points behind their counterparts in the Young Liberals, and more than 20 behind young women in the Italian and Spanish parties.

From interviews we’ve conducted with women and men from Young Labor and Young Liberal leadership teams over the past four years, these findings seem to be due to a mixture of factors. They range from the excessively adversarial “boy’s club” culture in both party youth wings to the tendency of men in the senior parties to mentor young men rather than women for electoral careers.

Other political career ambitions

Our results may make depressing reading for Australian political observers. However, when we asked youth wing members about a non-electoral type of ambition – the desire to work for the senior party in the future – we got a very different picture.

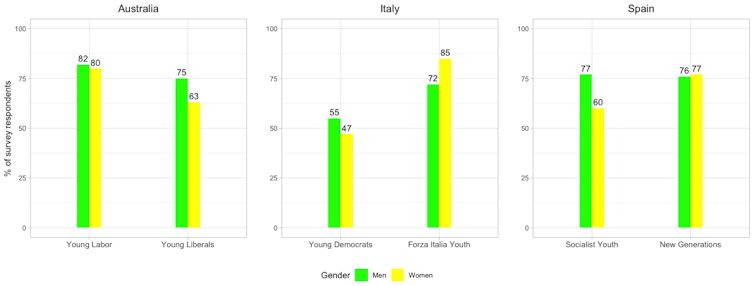

As the figure below illustrates, the political ambition gender gap almost entirely disappears among Young Labor members and narrows considerably among Young Liberals.

In short, our findings suggest it’s not that women in Australian youth wings necessarily lack political ambition. Rather, they may prefer to pursue behind-the-scenes careers, such as party officials and advisers, than stand as candidates at elections.

While we do find some similar patterns in Spain, the shift in the Australian results from electoral to non-electoral ambition is by far the most striking.

Where to go from here

So, what does all this mean for Australia’s major political parties and the women in them? To be sure, while the Liberals have evident problems in terms of attracting women members and candidates, Labor cannot rest on its laurels, either.

Both parties have serious imbalances in terms of the number of young women joining their youth wings compared to men, as well as in the proportion of young women compared to young men who aspire to stand as candidates one day.

Remarkably, despite all its good intentions, the Liberal Party review of the 2022 election does not mention the Young Liberals even once. This is a serious omission. If parties wish to improve their candidate pools of tomorrow, it’s vital they concentrate their efforts on the youth wings of today.

Duncan McDonnell receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Sofia Ammassari does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.