Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist '80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

You couldn't lob a broken glass bottle at a mohawked punk without hitting a sidescrolling beat 'em up back in 1993. Every arcade and console was stuffed with muscular guys in painfully tight stonewashed jeans bashing anyone and everyone with pipes or knives, only taking a break to kick phone boxes and piles of tyres to reveal the delicious life-restoring turkey or pizza waiting within. It was a different story for owners of Japan's PC-98, which is what makes Edge unlike any other brawler of its day. Games like that just didn't turn up there.

They didn't fit in with the standards of PC games at the time—if you needed an RPG of any kind it had a lifetime's worth to choose from, shelves across Japan heaved with adventures and murder mysteries galore, and every type of strategy and sim was accounted for. There were even plenty of shmups for those after something more action-oriented—this is the system that kicked off the phenomenally popular Touhou series, after all.

But belt scrollers, brawlers, and beat 'em ups? You may as well wish for Bloodborne on Steam.

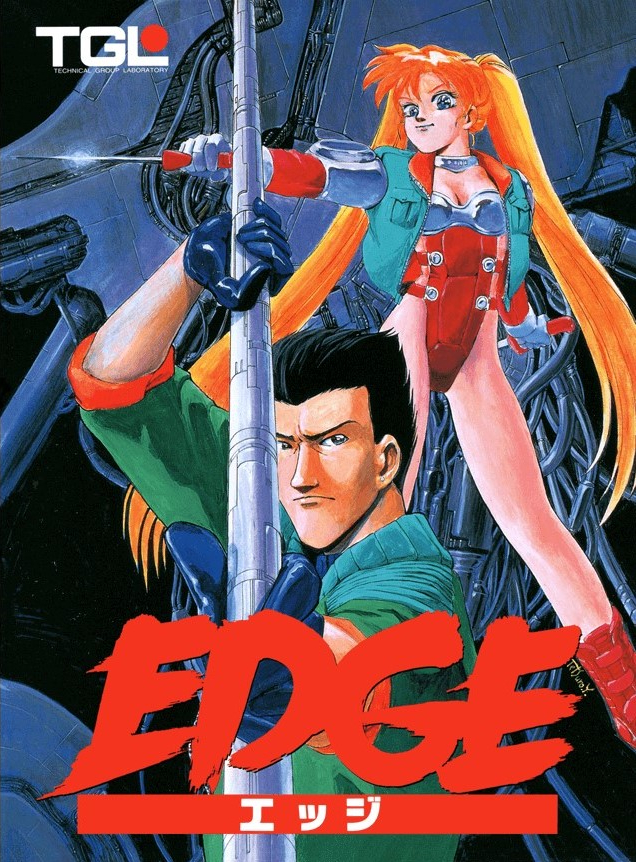

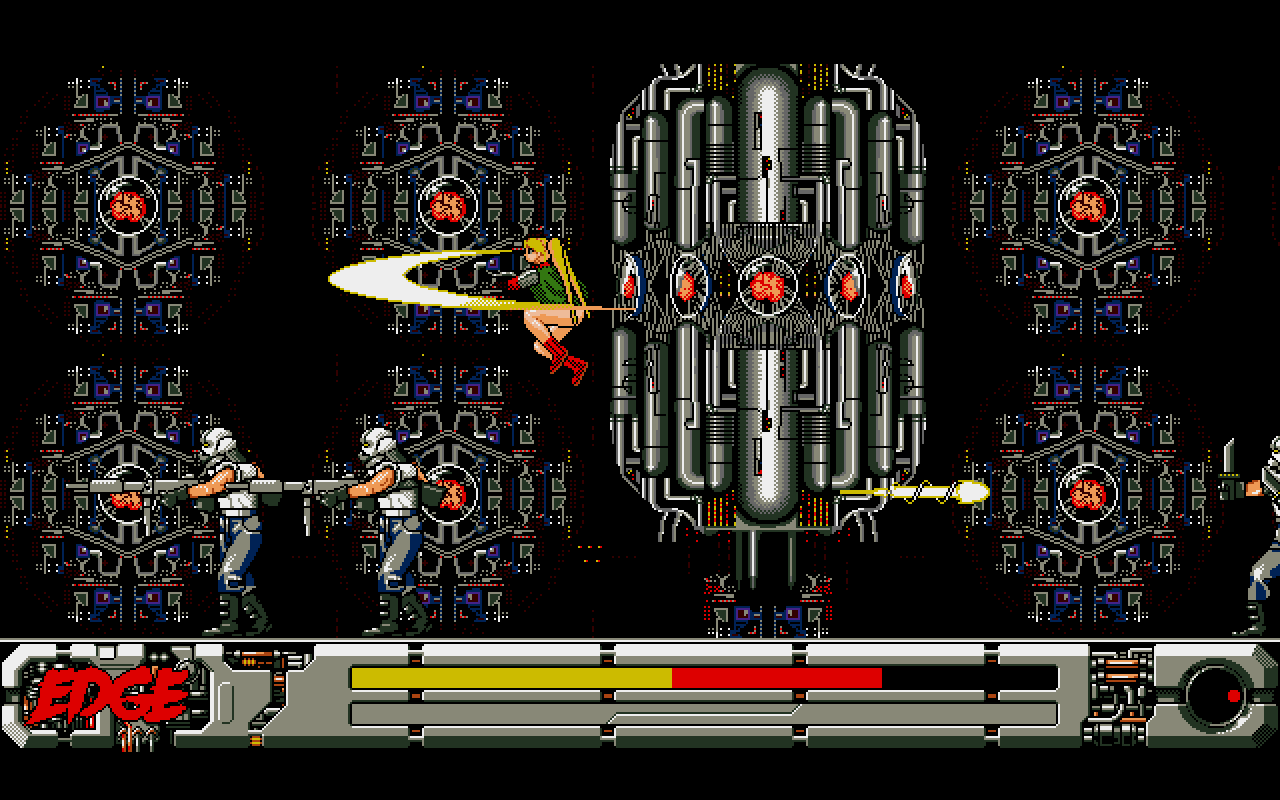

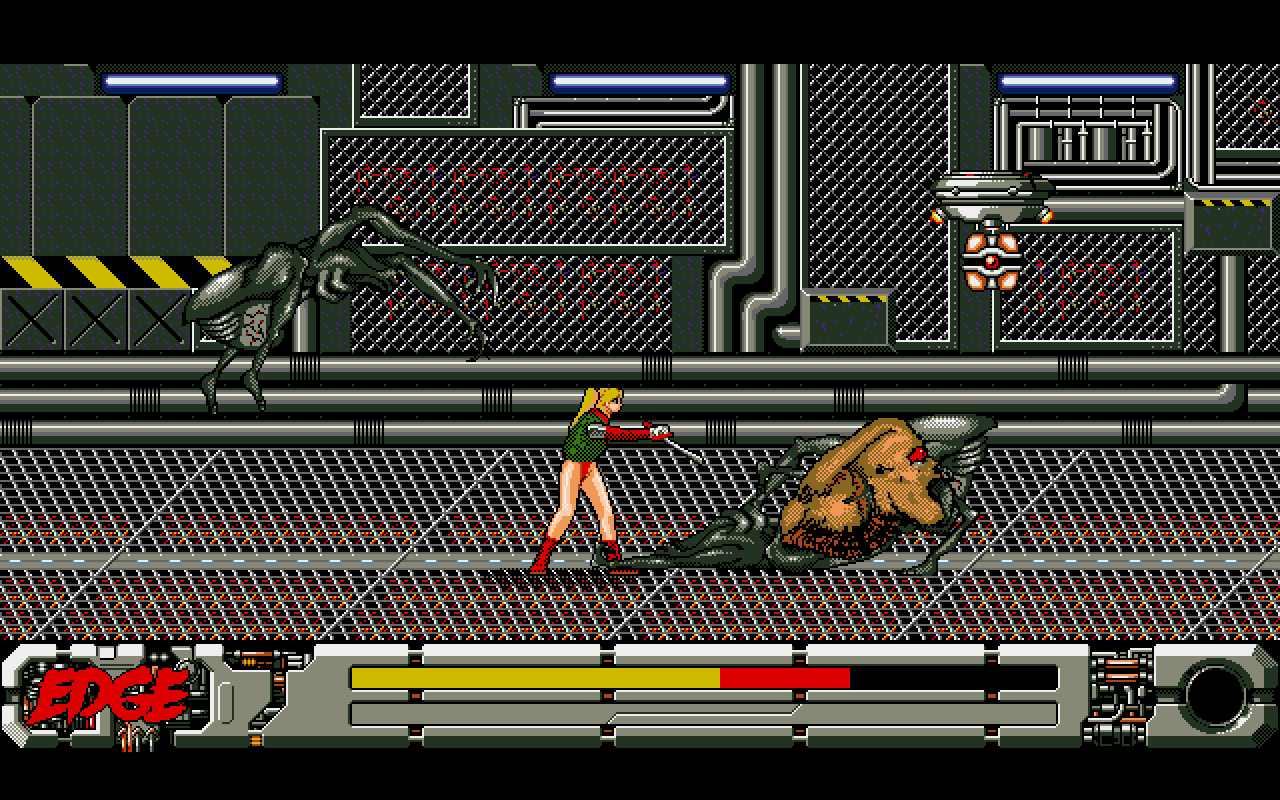

Under those circumstances Edge's cyberpunk techno-dystopian mix of ninjas and grisly bio-abominations were always going to stand out: it was one of only a miniscule number of similar games on the PC-98, period.

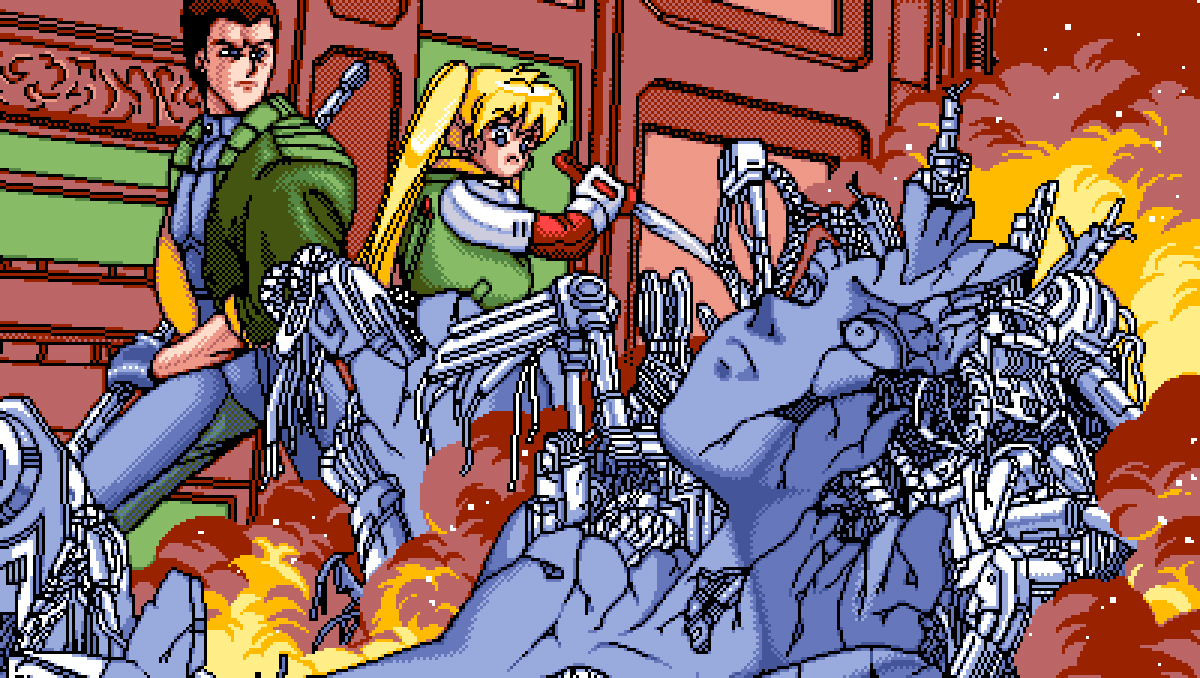

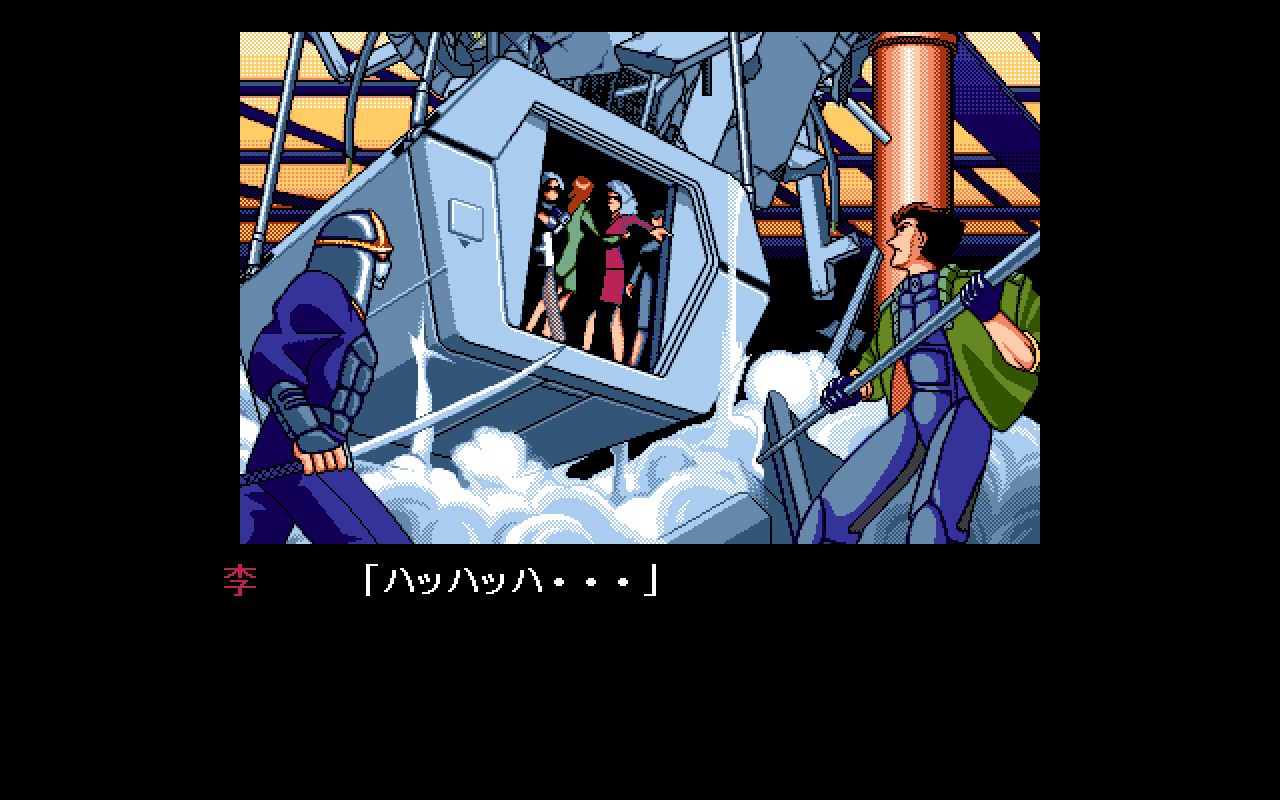

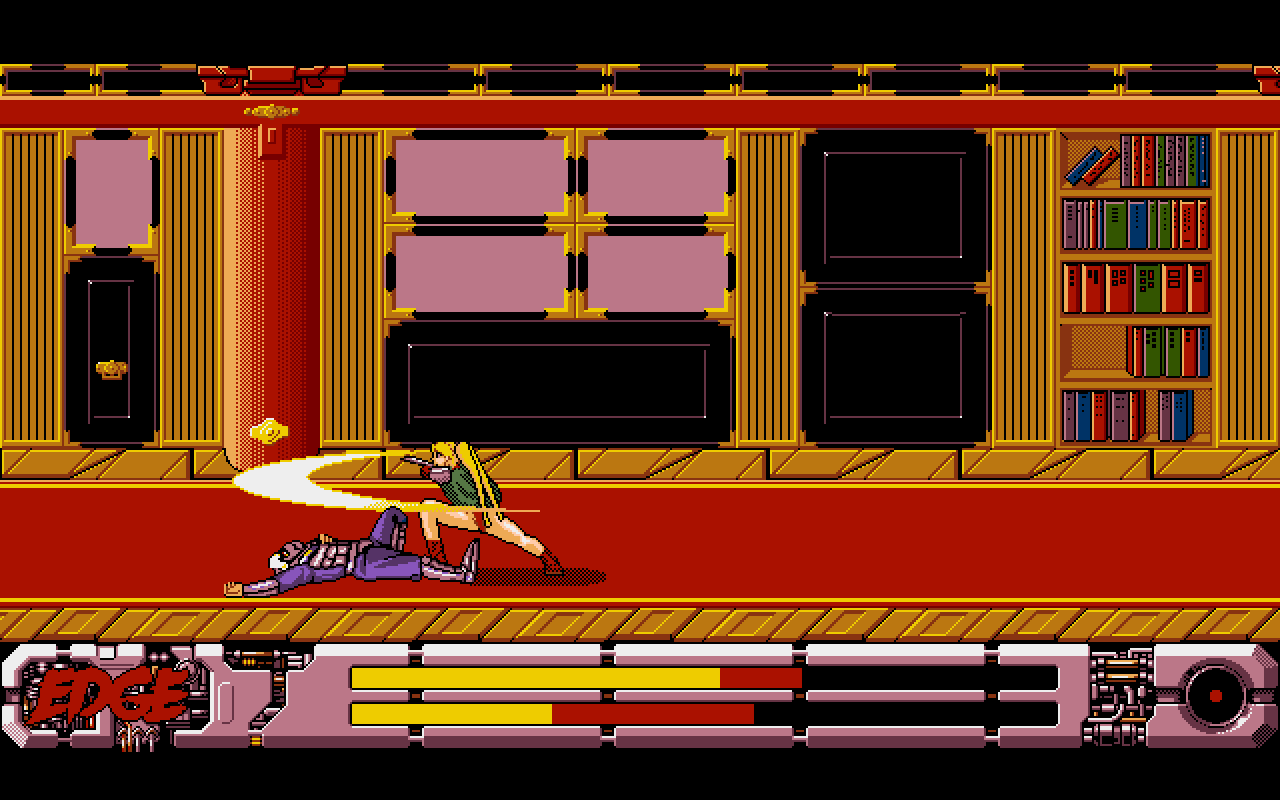

Edge's developers might've known they had a slightly older and more patient audience than the typical arcade game, so instead of rushing straight into the action it opens with a lengthy cutscene instead. This game loves cutscenes. Pretty much every change of scenery, new stage, and boss battle triggers one (before and after), almost all of them featuring more dialogue than most other belt scrollers have all game long, and often accompanied by some truly stellar '90s pixel art too.

I know I probably shouldn't like these intermissions—they keep me from the bits I actually paid money to play, after all—but the truth is I think they're great. Thanks to them Edge again stands apart from Final Fight and Streets of Rage. There are too few examples of the genre that actually make you believe the characters you're playing as (in this case staff-swinging Kikumaru or the sword wielding Rin) are working together. The levels don't just feel like disconnected, gimmicky setpieces. In Edge you always know why they've ended up wherever they are, and you might even have some idea of who's waiting for them at the end and where they're headed next too.

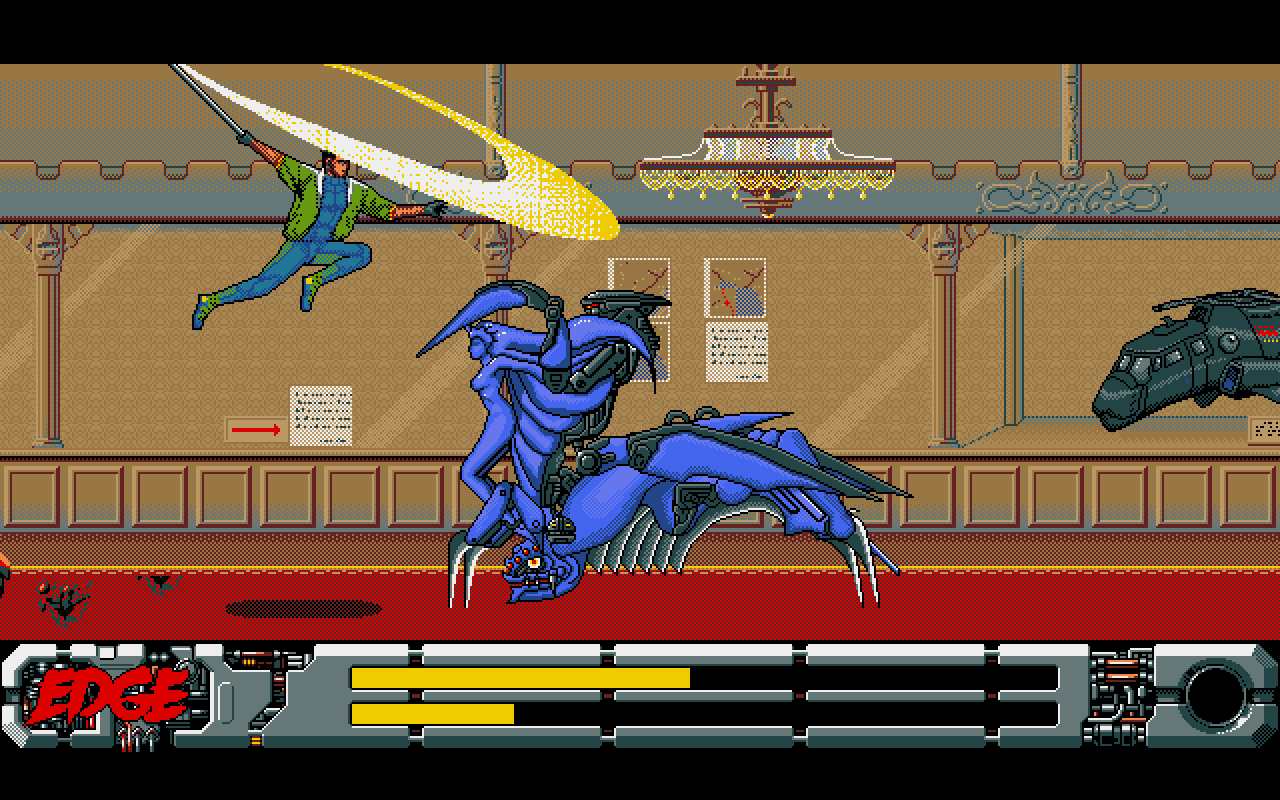

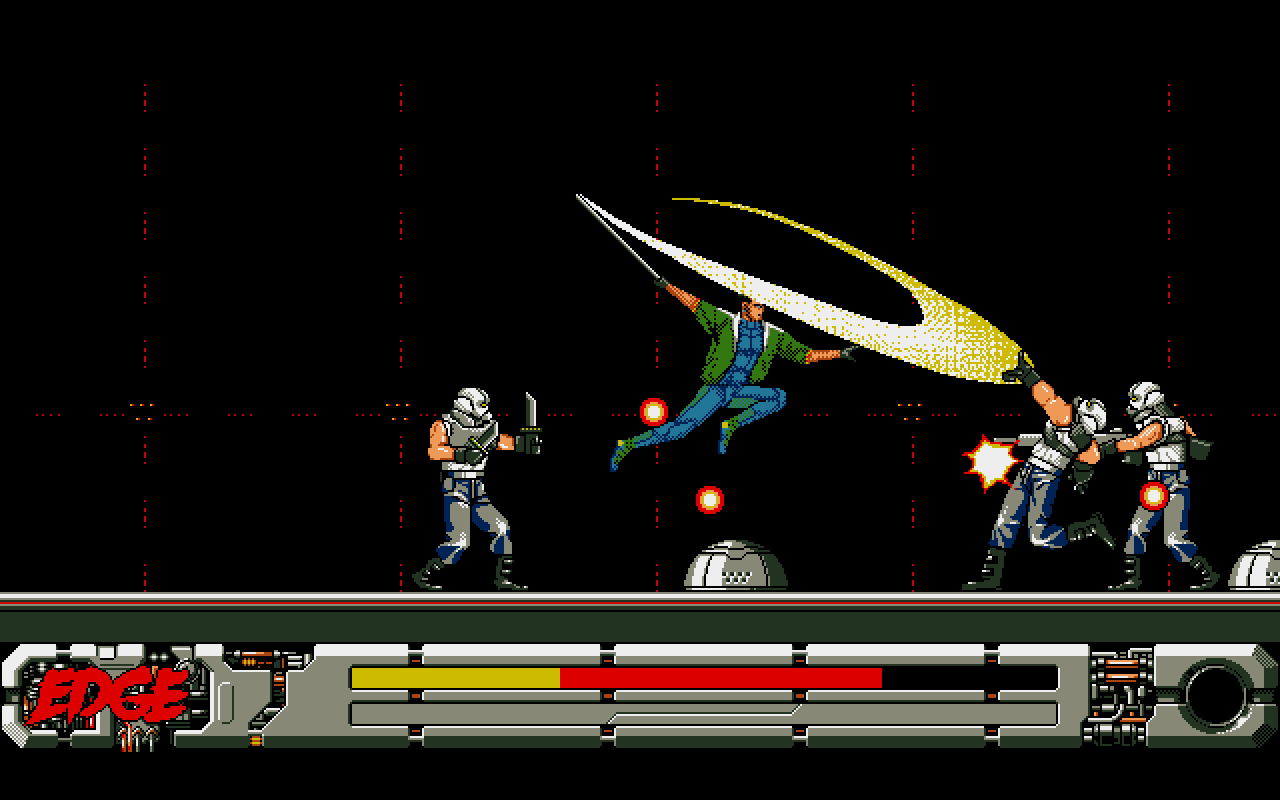

A belt scroller made for a computer with a keyboard control scheme sounds like a recipe for stiff-legged disaster, but again Edge subverts all expectations. Kikumaru and Rin both have a wide variety of useful moves at their disposal, from the expected life-sapping special attacks and throws to dash attacks, slide attacks, and even aerial dives on anything unlucky enough to be directly below them.

Whatever's happening—and the attacks really can come from all angles here—Edge gives you plenty of ways of dealing with it. The pair even have the decency to avoid the usual tough-but-stompy and weak-but-fast archetypes just for good measure, both of them capable of handling any situation thrown their way.

The above would normally be enough for any half-decent beat 'em up, but Edge takes things to the… well, you know. It dedicates a button to something that's still not seen often enough in the genre—blocking. Both characters can block any time they like and even perform a sort of "dash block," allowing them to push forwards without taking damage from any fists waiting between them and where they want to be.

This one simple move changes everything. Because you can block, you don't have to trade blows or keep ducking out of range of whatever leather jacketed thug tries to take a swing at you. You can get stuck in and stay there—if you're careful.

You'll always need to watch for openings and pick your battles, especially as you only have one life to clear an entire stage with—boss included—and there are never enough health pickups along the way to make you feel at ease.

Later on even the stages themselves start to exhibit Edge's love of carving its own path, moving away from flat left-to-right scrolling and adding a sprinkling of Strider's trademark verticality into the mix. You're invited to vault up hanging chandeliers to reach higher ground, grab onto ledges to avoid turret fire, and dash across undulating surfaces. It's also possible to rush straight past many enemies. Edge doesn't lock the camera in place and force you to beat up a roomful of guys as often as most beat 'em ups, although it's not a great idea to have what feels like every enemy in the stage chasing after you all at once.

In every way that matters, Edge feels like the impossible made real. A game like this has no business existing at all on the PC-98, never mind being any good. But it's not just good—Edge goes way beyond that; choosing to experiment everywhere it can, even introducing features that other modern belt scrollers could learn from. And all without ever losing sight of the fact that it must be fun to play above all else, not just clever and contrarian for the sake of it.