A Chicago mystery dating back to the Great Depression may have finally been solved.

What ever happened to Mary Agnes Moroney, the 2-year-old reportedly snatched away from her South Side family by a woman using the name Julia Otis on May 15, 1930?

The case made national headlines in the 1930s and 1950s. But its solution eluded investigators — and Chicago newspaper reporters — for nearly a century. Mary Agnes’ nephew, 55-year-old Don Moroney of Downstate Flanagan, has been searching for it since he was in high school.

Moroney is now convinced his aunt has been found. He believes Mary Agnes lived her life as Jeanette Burchard, who was raised as an only child, married twice, had three children and spent more than 50 years as a nurse. She died about 20 years ago in Florida at the age of 75.

Also convinced is Burchard’s daughter, Terri Arnold of Florida, who has suddenly found herself entangled in a historic Chicago cold case.

Arnold said she was contacted in September by a Cook County detective, who had questions about Arnold’s late mother and asked if Arnold would be willing to take a DNA test. She told the Chicago Sun-Times this week that she’s since learned “my family is completely different from what I was always led to believe.”

And she said she’s “very confident” her mother was Mary Agnes.

Arnold said her mother loved her pets, opera and the Miami Dolphins. Her life apparently began in Chicago. But most importantly, Arnold said, “she was the world’s greatest mom.”

“We adored my mother,” Arnold said.

A granddaughter of Burchard, Lori Hart, acknowledged the pain that Mary Agnes’ disappearance must have caused the Moroneys. But she told the Sun-Times she was still “blessed” to have had Burchard as her grandmother.

“Any time I needed her she was there,” Hart said.

Moroney, Arnold and Hart believe Burchard was Mary Agnes because of the work of Cook County Sheriff’s Det. Jose Rodriguez. He was assigned last June to investigate Mary Agnes’ disappearance as part of Sheriff Tom Dart’s Missing Persons Project.

Rodriguez and Cmdr. Jason Moran said commercial DNA testing revealed a genetic association between Arnold and members of Don Moroney’s family suggesting they were all cousins.

That left Arnold trying to make sense of a new family history. But it also offered closure to the Moroney family, which has been at the center of the case for 93 years. Mary Agnes’ mother, Katherine, was haunted by the loss of her daughter and fell into a deep depression. Katherine died in 1962, at the age of 49.

Mary Agnes’ father, Michael, died in 1957 when he was 58. His final words were said to be, “they never found my baby girl.”

Don Moroney said the family had always hoped, whatever happened to his aunt, “that she led a good life and she was taken care of.”

“And she was,” Moroney said.

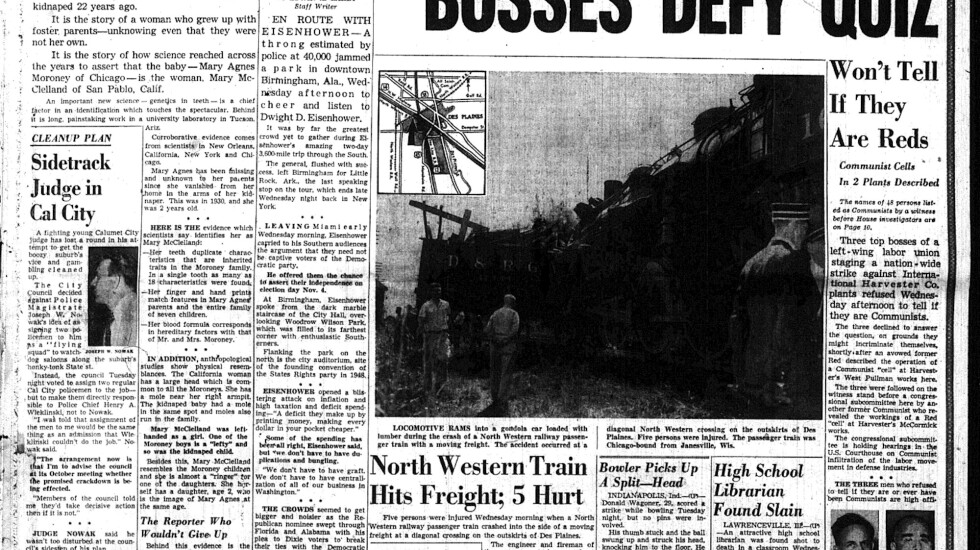

The family members’ confidence sets this latest development apart from previous attempts to identify Mary Agnes. In 1952, the Chicago Daily News, which later became a sister publication to the Sun-Times, reported that one of its reporters had found her.

But Moroney said Mary Agnes’ mother never bought it. A DNA test proved the newspaper wrong decades later.

The Sun-Times pursued the case again in 2018 — only to have another DNA test rule out a long-lost Moroney family friend.

Even now, the Cook County sheriff’s office says it cannot take steps necessary to confirm that Burchard was Mary Agnes. Rodriguez and Moran explained that going further would likely require the exhumation of Burchard and Mary Agnes’ mother.

“I already told them, in the beginning, no,” Arnold said.

And that extreme step would likely do nothing to answer other lingering questions that may never be resolved. Arnold told the Sun-Times that she’d never before heard the name Julia Otis. And she doesn’t know how her mother came to be raised by Arnold’s grandmother.

“All I know is, she ended up with her, and I just feel bad that the parents never knew what happened to their daughter,” Arnold said.

Either way, Arnold said “the Moroney family can honestly, truly know that she was loved very much.”

The story of Mary Agnes Moroney

Mary Agnes was born May 10, 1928. She was the first child of Katherine and Michael Moroney. The couple started their family just before the Great Depression hit, and they lived in an apartment over a grocery store at 5200 South Wentworth Ave.

“My grandparents were very poor,” Don Moroney said. “And they put an article in the paper asking for help.”

Soon, a woman came calling with food and gifts, using the name Julia Otis. Katherine, 17, was pregnant with her third child. But she let the woman into the family’s home, where Mary Agnes was playing on the floor.

The visitor took notice of Mary Agnes and began talking to her about going to California. That made Mary Agnes’ mother uncomfortable, though, and the woman left. Still, she came back the next day with more gifts for the family. She asked if she could take Mary Agnes shopping for clothing.

Katherine agreed. The woman took Mary Agnes and never returned.

“Mary Agnes — from what I’ve read and from what I’ve heard — was having a fit,” Don Moroney told the Sun-Times. “Did not want to go.”

Mary Agnes’ parents reached out to the police and began to search for their missing daughter. But a letter arrived the next day, purportedly from Julia Otis. It said Mary Agnes had been taken to California, and that the girl would be returned in a month or so. A similar letter followed, claiming to be from the kidnapper’s cousin, Alice Henderson.

It said that Otis’ child had recently died, that she’d earlier lost her husband, and that she had suffered a nervous breakdown. It assured the Moroneys that Mary Agnes would come home.

Police scoured Chicago’s railroad stations for any clue that Mary Agnes had been taken on a train, according to the Chicago Daily News. Katherine Moroney obtained a warrant from a judge charging Otis with Mary Agnes’ kidnapping, the newspaper reported.

But they were never found. Years passed. The Moroney family continued to grow — the couple eventually had eight children, including Mary Agnes. Still, Katherine Moroney struggled. The Chicago Daily News wrote that Mary Agnes’ kidnapping had “eaten into her like a cancer.”

Meanwhile, stories about Mary Agnes would appear in the newspapers now and then, particularly when other children went missing. Her story eventually caught the attention of Chicago Daily News reporter Edan Wright, who noticed something about the Moroney family in a photo.

“All the members of the family resembled each other,” the newspaper wrote.

The Chicago Daily News convinced a California newspaper to print pictures of the Moroney family, hoping it would lead to Mary Agnes. The pictures were apparently spotted by a man who claimed one of Mary Agnes’ sisters “looked so much like his wife that it could have been her photograph.”

His wife, 24-year-old Mary McClelland, had been adopted.

On Sept. 3, 1952, the Chicago Daily News ran the following words atop its front page: “22-Year Search for Kidnaped Baby Ends.” It claimed characteristics in McClelland’s teeth helped identify her as Mary Agnes. And the newspaper arranged a meeting between McClelland and Katherine Moroney.

Don Moroney said his grandmother had the following reaction after she met with McClelland: “She’s a great lady. Fantastic person. I wish she was my daughter. But no.”

Not only that, but McClelland was missing two of Mary Agnes’ distinguishing features: A strawberry birthmark on her cheek and a scar from a herniated navel.

Still, McClelland became a close friend of the Moroney family. Don Moroney recalled visiting the Museum of Science and Industry with her. “Never once did she say she was my aunt,” he said. “Never once.”

Eventually, Moroney said a DNA test revealed that McClelland was not Mary Agnes. He said the test was performed in 2008, following McClelland’s death.

McClelland was not the only person who responded to the photos in the California newspaper, Don Moroney said. Another woman also wound up becoming close with the Moroney family. She even signed a photo for Don Moroney’s father as “your sister.”

The family fell out of touch with that woman, but the Sun-Times located her in 2018. A DNA test determined she could not be Mary Agnes, but she and Don Moroney have remained in contact.

The story of Jeanette Burchard

Jeanette Burchard’s family was told she was born on April 14, 1928, that her biological father died two months after she was born and that she spent the first six years of her life in Chicago.

She was raised by Jeanette Celarek Derris Anderson and a stepfather, Frank Derris. The pair raised Burchard as a devout Catholic. She was well-educated, never hungry and “never abused at all,” Arnold said.

“Anything my mom needed when she was a kid, she had,” Arnold said.

Arnold said her mother would visit Chicago occasionally, the last time likely being for a funeral sometime between 1989 and 1995.

Rodriguez said his investigation revealed nothing obviously amiss about the family. But Arnold shared one clue: She said Frank Derris once told Burchard that the woman who raised her “was not her natural birth mother.” The comment was never explained, Arnold said.

“My mother went as far as asking her cousins up in Chicago,” Arnold said. They told Burchard they didn’t know anything about it.

Arnold said she also recently learned that the woman who raised Burchard had a short-lived marriage before she married Derris. That earlier marriage was to a man named John Fahey. A 1930 Census record online appears to show the couple lived together in Chicago at the time, along with Arnold’s mother.

Following the marriage to Derris, the family moved to Virginia around 1934, Arnold said. They moved to Florida during World War II. Burchard married Edward Jennings, Arnold’s father, in the 1940s. Decades later she married again, that time to Earl Burchard. Both of her husbands have died.

She had three children. In addition to Arnold, Burchard was the mother of Barbara Joan Jennings, who died in 2006, and Edward Cliffton Jennings Jr., who died in 2004.

“She loved us completely,” Arnold said.

Burchard spent more than 50 years as a nurse, her daughter said. And in addition to her children, she loved her dogs and cats. Arnold said Burchard would have her pets cremated when they died, and she was buried with the remains.

She loved opera — especially “Madam Butterfly.” And from the day the team was founded in 1966, she was a fan of the Miami Dolphins.

When Rodriguez first reached out to Arnold about Burchard, Arnold said she didn’t believe the detective’s theory. She said her mother was missing Mary Agnes’ birthmark, as well as other distinguishing features.

“This can’t be right,” she said at the time. And, she added, “I don’t think my grandmother would ever do anything like this.”

But she said she was willing to take a commercial DNA test to prove the detective wrong. The results came back Oct. 28, she said, and revealed all was not as it seemed. Though the maternal side of Burchard’s family was Polish, Arnold said her DNA results revealed she is not. She is mainly Irish.

The Moroneys are also Irish.

That’s when Arnold said “the anger thing set in, quite a bit with my grandmother.” Friends and family later stressed to her that, had life not played out the way it did, “you wouldn’t have had your mom.”

Months later, Arnold and the Moroneys have now spoken several times by phone. Both sides said they’ve enjoyed getting to know one another. Arnold sent photographs of her mother to her new cousins. And she said her mother would have loved being part of a big family.

Arnold said that, if her mother were still alive to learn the news, she’s sure she would have reached out to the Moroneys.

“She would have gone to the family,” Arnold said. “And said, ‘I am here.’”

“I’m fine.”