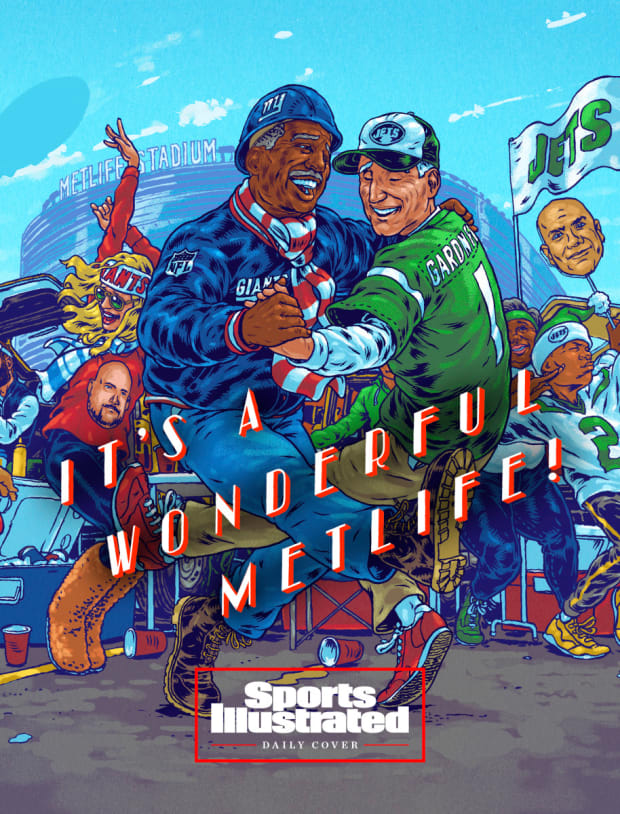

So maybe not everyone in the New Jersey–New York metropolitan area is enjoying this autumn renaissance, the Jets and Giants sporting winning records at the same time, for the first time since 2015.

Take Jeffrey Lahullier, for instance. He’s the mayor of East Rutherford, the northeast New Jersey borough in which MetLife Stadium lies. In an email response to questions about the windfall of good fortunes that competitive football brings to his borough specifically, he listed a handful of complaints. For one, the state police are assigned to patrol traffic, but he ends up having to put East Rutherford cops on the outer roadways, which is an additional cost not reimbursed to the borough. He’s also still unhappy about the way he was told not to use any NFL signage or logos to promote events in the town back when New Jersey hosted the Super Bowl in 2014. He says he doesn’t really see an influx of overjoyed fans trekking into Rutherford proper and patronizing the restaurants there.

“We may see a spike in our municipal court revenues due to unruly fan activities taking place at the stadium,” he says. “These fines would be directed to our local borough court but not a windfall of revenues by [any] means.” He signed off his email apologizing for “muddying the water.”

Illustration By Andrew DeGraff

But in a suddenly bustling football town, this is merely balance, which might be healthy for fans of these teams given the relative hysteria the greater metropolitan area was under the last time the Jets and Giants were good. In case you’ve forgotten, Rex Ryan was the coach of the Jets. Tom Coughlin was the coach of the Giants. The Jets made it to a pair of AFC championship games. The Giants won a Super Bowl. The Jets put a picture of a bloodied Eli Manning on the cover of their game-week notebooks, celebrating a random preseason sack. Coughlin barked a steady stream of modern Patton-isms. Ryan’s press conferences were attended not just by sports reporters, but by journalists from Extra. A lot of people yelled at one another, with Giants running back Brandon Jacobs admittedly coming close to punching Ryan on the field.

Certain reporters of that era (raises hand) still get nervous stomach pains when thinking about game day at MetLife Stadium. The heft and sheer force of the attention was unfathomable, but so, too, were the advantages to businesses and individuals around the state (outside of East Rutherford, perhaps), which former New Jersey governor Richard Codey told me said equated to “millions and millions” of dollars.

“It means a lot,” Codey, one of the most influential lawmakers in the history of the state, says. “An awful lot.”

Life is different now, and not just for journalists and politicians. The Giants have already beaten teams quarterbacked by Lamar Jackson and Aaron Rodgers this year. The Jets, on Sunday, logged one of the most significant regular-season wins in recent franchise history, beating the Bills at home. This would have qualified as more than simply surprising a year or two ago; it would have been nearly impossible from a talent and schematic perspective. While it is a big deal to have both New York teams potentially playoff bound (according to FiveThirtyEight the Giants have an 78% chance of reaching the playoffs, while the Jets have a 59% chance) the milieu of both teams is drastically different. Their existence is decidedly less combative. Both coaches—Brian Daboll and Robert Saleh—are a mix of situationally fiery and subtly Zen. Young players unaware of the past (both in terms of the teams’ recent history of struggles and their more distant past as lightning rods in the country’s biggest market) are forging their own organic bonds with the area.

And for many who operate on the fringes of a thriving football ecosystem, that makes not for a wild life; not a chaotic life that produces a gigantic, overwhelming, overstuffed big-city fever dream. It makes for, simply, a nice life.

You can hit Redd’s bar in Carlstadt with a wind-aided punt from the MetLife Stadium parking lot. The place has been there since 2002, passed down from one generation to the next. Doug Palsi, the current owner, still works with his 88-year-old mother, Elsie “Tootsie” Palsi, who buses tables and runs the hostess stand. His father, John Jr., worked there until his death in 2018.

They are unique in that they are somewhat event-dependent to pay their bills, but they are not owned by some massive food-group conglomerate. The road to MetLife Stadium is pickled with Starbuckses, Targets and Burger Kings hoping to siphon a few patrons among the game day traffic. Most of what they have came from hard work and good ideas, like when Palsi’s father came up with the concept of busing folks to and from the stadium’s parking lot 20 years ago. You can still drive to Redd’s in the morning on game day, pay a small fee and avoid the terrifying prospect of thousands of cars converging onto narrow roadways. You can have a few drinks at the stadium with peace of mind.

The problem with this business model is that it’s not pandemic-proof. Empty stadiums meant vacant bars, no liquor sales. Twice—once during the initial surge and again when COVID-19’s Omicron variant swept through the country during the holidays last year—he was wiped out, Palsi says. Redd’s scrambled to apply for loans and grants. Some of them came through, and others, like the restaurant revitalization grant, did not.

Food prices are astronomical. So is cooking oil. “We’re always chasing our tail,” he says. “Life of a small business, man.”

Courtesy of Doug Palsi

Palsi says they are a real example of team success directly benefiting a local business. Think about it this way, he says: The Giants and Jets have not been relevant past October in years. As a responsible business owner, he has to forecast November and December as having diminished sales. There are fewer people going to the games and fewer people coming to the bar, which is a non-stadium destination for a lot of local fans who aren’t going into the stadium but want to be in proximity to the game day vibe.

This year, he says he can now safely assume November will bring a steady stream of customers. December, once a pipe dream, is now in play. It also impacts the following year, he says, because the Giants and Jets will now be more attractive as a prime-time entity. Palsi said that 4 p.m. games and 8 p.m. games are ideal for the restaurant business, because there is more pre- and post-game continuity among the customer base. For 1 p.m. games, he sells his fair share of Bloody Marys and mimosas but would love to roll out the entirety of the liquor cabinet and keep customers there longer.

“It means the world to us; it really, really does. The fact that they’re relevant and it’s mid-October, that gets me through November. It’s been a long time since we’ve had meaningful football here. It helps the bartenders, and the cooks are working more. Especially for a mom-and-pop like us.”

The difference between last November and this November could be “double,” Palsi says. “It’s so big. Every little penny helps.”

When asked what he could do with the money specifically, Palsi says he could start to chip away at some of the pandemic loans he took out, which he would not have been able to do if the Jets and Giants were flailing. A home playoff game in January is the next manifestation he hopes will become a reality. Despite “this Josh Allen Banana” and the “jerky Eagles,” it feels closer than it has in years.

At 9:10 a.m. on Oct. 25, the Jets’ official Twitter account posted the following message: gm Jets fans how we feelin’

The responses were a mix of praise for the team’s recent trade for running back James Robinson—a signal that they were serious about competing this year—and other genuine expressions of gratitude for being in contention. One reply read: “Big picture, feeling great. 5–2, culture has changed, winning games we historically lose and seem to have the GM and coach. Assuming Zach stays healthy we’ll know this year but concerned. Crushed about [season-ending injuries to] Breece [Hall] and AVT [Alijah Vera-Tucker] but they’re young and will be back.”

Another respondent wrote: “It’s just great to see Jets fans happy and I’m not even a Jets fan.”

Noah K. Murray/AP

Contrast that with the replies to most tweets from 2016 to ’20, and the difference is obvious. An example: A few days after Christmas in ’19, the team posted a video of then star safety Jamal Adams handing his teammates Jordan brand sneakers for the holidays. The replies were chastising the team for having a losing record, or with multiple people threatening “to go to jail” if the team traded Adams. Most other tweets were, in some roundabout way, requests to fire and cut nearly everyone else.

Eric Gelfand is the vice president of communications and content for the Jets and oversees the team’s social media operation, the makeover of which he spearheaded, starting a little more than a year ago. He says the team’s current social media strategy began “in breadcrumbs” at the beginning of the Robert Saleh–Zach Wilson era. Gelfand, in concert with team ownership and president Hymie Elhai, knew that the Jets had to do a better job of embracing their New York–New Jersey essence. That meant posting more often, and being more creative and expressive in their tone. Last week, for example, following a win over the Broncos, the Jets’ Twitter account posted a scene from Parks and Recreation, edited to make it look like the people at the town hall meeting (the Broncos) were finding losses under their seats.

Since the implementation of their new strategy, the Jets’ social accounts have been among the fastest-growing in the NFL. Gelfand says that they were specifically commended on a recent call of the NFL’s team presidents. They are currently in the top five in all major Twitter metrics and third in the league in TikTok follower growth this season. Previously, he says, most of the team’s metrics had peaked in the offseason (new coach, new draft picks) and tailed off during the season.

“It was really about our volume and a little bit about our tone,” Gelfand says. “We dialed down our volume [in the past] and we got a little too quiet. That hurts you. We made a conscious decision at that point that we weren’t going to take our foot off the gas in terms of posting volumes on all platforms.”

He adds, “This year has remained consistent. We set a baseline in 2021, and the content within the volume may be a little more amped up, which is what you’re probably seeing.”

While it’s not as simple as winning equals a bustling (and probably far less macabre) social media environment, some of the philosophies behind the Jets’ rebuild can have a tangential effect on how they present themselves. In short: The players are personable and likable and, yes, successful, which allows them to act more consistently in a way that accentuates what makes them personable and likable, which makes for enjoyable social media content.

In Pittsburgh, Wilson caught a touchdown pass on a version of the Philly Special and punctuated it with the “Griddy” dance. Before the team boarded its flight home, there was already a TikTok video of Wilson griddy-ing his way out of the stadium, and then across the state of Pennsylvania back to the facility in Florham Park. It generated millions of impressions.

After victories, the team receives and posts videos from Johnny, an adorable little kid who, in the perfect meandering hoarseness, recaps the team’s victories and dives into ice cream, which his parents promised him after each victory at the beginning of the season. He is getting a lot of ice cream.

It’s another instance of the real-life, trickle-down implications of success. Someone parked inside the Jets facility is awaiting his latest installment, happily readying a piece of social media video that will spread joy to a fan base moving beyond sarcasm as a primary language.

Walk down Broadway in Denville, N.J., and stop at the place that smells like what you’d expect from Santa Claus’s kitchen.

Helene Garneau doesn’t need the attention. On Mother’s Day the line is out the door, down the street and backed up into the crosswalk. People drive hours from Connecticut to have the beignets here. The fried pastry covered in powdered sugar is the best representation of the New Orleans staple outside of Café Du Monde. She makes donuts, too, with a cake-like sponge inside the golden-fried ring that melts the second it hits your tongue.

Not long ago, the wife of a Jets player walked in and was blown away. Now, Garneau and her co-founder, nephew Clif Gauthier, deliver four dozen beignets and two dozen donuts to the team’s facility every Saturday. Or, she sees some wide-eyed rookie popping into the little shop to pick up a box before meetings. She laughs, when she notes that the one time they forgot to place an order this year, the team lost. She has established a position of power as a talisman of the Jets’ good fortunes, due in part to the Oreo Explosion donut consumed feverishly inside the team’s Florham Park facility.

“I’m so happy when they come in,” Garneau says. “And they’re so nice.”

Or that place in Bergen County called Casa de Montecristo. The cigar store. After victories, there have been viral clips of Giants coach Brian Daboll slipping out the back door of the stadium to high-five fans with a massive stogie in his off hand. His preferred smoke of choice is a Padron 1964, which is aged for almost half a decade before it sees the light of day. Bryan Cox, the team’s assistant defensive line coach, shops there, too. (He’ll smoke anything from Drew Estate, though he’s currently mowing through a lot of Olivia brand.)

Phone the place and they’ll talk about plans for Giants tailgate parties in the future, and how much they love a steady stream of Giants faces walking through the door.

When we think about good football in New York and New Jersey, we think about noise and clamor. We think about being loud and thumping our chests. We think about big money, big corporations helicoptering into the country’s largest stage and sucking up all the profit.

This time around, everyone is trying it a little differently. It might signal something of a purposeful endeavor—a learning of lessons, a way to keep the enormity of it all from collapsing the whole operation. Maybe it’s just too early to tell, and as the Yankees’ and Mets’ postseason failures fade from the rearview mirror, football is, once again, about to be tussled about like the most popular toy on the daycare floor.

Or, perhaps, everyone here is just deciding that winning in New York and New Jersey doesn’t have to mean what it used to mean. Victories can be big and small. A nice tweet, a good cigar, a smaller balance on the loans and a few more bucks in the pocket of a bartender who has more regulars to tend to these days.