That’s Marshawn Lynch on the Zoom screen in mid-December, clad in a black sweatshirt, hood up, G-U-C-C-I in rainbow letters across his chest. Smoke twirls overhead from two wine-flavored Black & Mild cigars. Oversized white headphones dangle near his ears.

He makes one thing clear immediately. Despite a robust career highlight reel, built over 12 decorated, bruising and, shall we say, distinct NFL seasons, he is best known for The Handoff That Never Happened. Or, as Lynch puts it, “My biggest play of my career had nothing to do with me.

“How long ago was that play?”

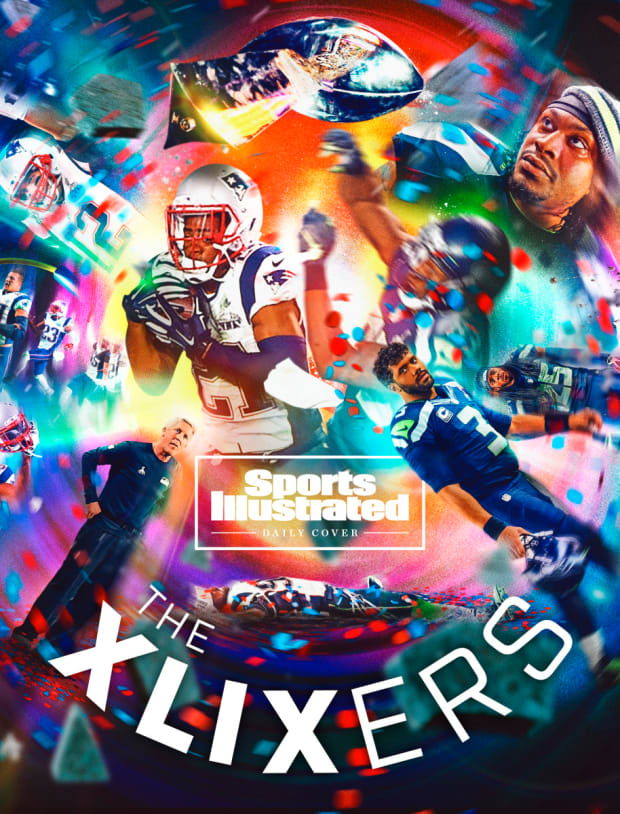

Photo Illustration by The Sporting Press. Photographs by Simon Bruty (3); Robert Beck (2); John W. Mcdonough (2); John Biever; John Iacono; Donald Miralle; Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Almost eight years have passed since that night in Arizona, the last time the site of this year’s Super Bowl hosted the event. Lynch lets out a sigh, one born more of disbelief than resignation, over second-and-goal from the 1-yard line in the final minute XLIX. He says the day before this interview, a stranger approached him: “Man, I wish they had gave you the ball in that Super Bowl situation. . . . ” Lynch says he hears that at least once a week.

“I don’t even think about it—” He stops himself, foregoing a more palatable answer. “Nah,” he says, before unleashing a cackle and saying he will be “straight up.”

“I was gonna say I don’t think it’s so much the fact that, if you give me that ball, we’re gonna score. But more just what we had built in Seattle: tough-ass defense and strong-ass run game. If we were going to win or lose, you would want to see it go down that way … especially given the opportunity of how it could have played out.”

Instead, everyone remembers Malcolm Butler, the undrafted rookie cornerback who stole the Lombardi Trophy with a goal line interception, securing the Patriots’ 28–24 victory. The play represents the most drastic turn of events in the history of the NFL’s biggest game. But Super Bowl XLIX contained so many other moments that could have altered careers and legacies. For many who watched that night, those plays are lost to time. But those who played remember, just as much as they still feel the game’s aftermath almost a decade later.

Julian Edelman is calling from Manhattan, after a taping for Inside the NFL. It’s part of a life that hardly resembles what it was eight years ago. For one, he’s a father, which means ferrying his daughter to soccer practice and gymnastic meets, while adjusting to post-football endeavors around the house. “A lot of time at Home Depot and Bed, Bath & Beyond,” he says.

He’s also something of a mogul these days. He was nominated for an Emmy last year for his pro football analysis on Inside and currently has a scripted comedy project in development with Paramount+. He co-hosts a podcast for Coast Productions, a media company he co-founded, with comedian Sam Morril—there might be a tie to XLIX there too.

Edelman entered that season—fresh off his breakout 105-catch campaign in 2013—unbearably ringless. It had been a decade since the Patriots’ last Super Bowl victory, and Edelman, then a sixth-year receiver, was sick of hearing about the Troy Brown–Tedy Bruschi–Willie McGinest glory days. They had won titles, shaped a dynasty, deserved all the accolades, but that generation of Patriots was gone. A championship for Edelman’s Patriots would mean his team would “finally start [a generation of] our own.”

That winter, he remembers the team’s crisp preparation for the Super Bowl in Arizona; he liked what he witnessed on a heavily guarded practice field. The Patriots fine-tuned with urgency, everyone fast, everyone serious. The offense executed with end-of-the-year precision. There was one outlier, a specific play the defense was struggling to cover. One of the Seahawks’ offensive tendencies was to utilize a Twin WR Stack in the red zone. The Patriots wanted Butler to slide inside fellow cornerback Brandon Browner on that play, covering the wideout who was slanting. But against New England’s practice-squad offense, Butler could not get there; he was getting smoked, every time. At one point, Edelman thought, Oh, f---. I hope they don’t run this play.”

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated

But to Edelman, the game-altering moment in Super Bowl XLIX came at the end of the first quarter. Bill Belichick and the Patriots’ coaching staff had the utmost respect for the Seahawks’ defense, particularly a group of defensive backs known to most as the Legion of Boom but referred to in the Patriots’ building as The Seattle Six. There was also deep concern for defensive end Michael Bennett’s game-wrecking ability. The plan was to run right at Bennett with big back LeGarrette Blount, with the idea of wearing him down like a boxer who has to absorb a series of body blows early in a bout.

Pete Carroll and defensive coordinator Dan Quinn caught New England off-guard early: Edelman says the “zone-beater” routes the Patriots had prepared to counter the Seahawks’ famed Cover 3 defense hadn’t come into play—Seattle surprised them by leaning heavily on man coverage early. The game started off as a slog (both teams were scoreless 20 minutes in). With a little less than two minutes left in the first quarter, New England facing third down at the Seattle 10, the Seahawks’ defense made a play—and paid a price.

Jeremy Lane, Seattle’s nickel corner, intercepted a Tom Brady pass and was upended by Edelman during the run back. In bracing his fall he sustained a gruesome injury: Above his left wrist, his arm snapped. It was revealed later that Lane also tore his ACL on the play.

Beginning with their next possession, it was clear that Brady was targeting anyone matched up with Tharold Simon, Lane’s replacement. Edelman would get his shot later, but the game’s first points came when Brady found Brandon LaFell on a slant route, with safety Earl Thomas crashing into Simon as LaFell crossed the goal line.

Jermaine Kearse reclines on a couch in the golf center he recently opened in Redmond, Wash. The former Seahawks receiver is discussing his friend’s frustrations, and he can’t stop giggling.

Subsequent film reviews confirmed Doug Baldwin’s feelings: He was open, sometimes absurdly so. Kearse says Baldwin has saved clips of this on his iPhone. “Guarantee it’s in his favorites,” Kearse says. He’s giggling again. “I mean, Doug was open a lot. Just ask him.”

“I was murdering him,” Baldwin says of Patriots cornerback Darrelle Revis, who spent most of the game shadowing the veteran receiver. That Baldwin wouldn’t get a target until late in the third quarter, even as Seattle struggled to move the ball early in the game, was one harbinger of the team’s coming discord.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

Fortunately for Seattle, Chris Matthews went off. Unknown until he recovered an onside kick during the Seahawks’ comeback win over the Packers in the NFC title game, the 6' 5" Matthews grabbed a jump ball for a 44-yard catch in the second quarter, his first NFL reception outside the preseason. It set up a Lynch touchdown to get the Seahawks on the scoreboard. Then Matthews finished a frantic 30-second drive at the end of the first half with an 11-yard TD grab. He won downfield again on the third play of the third quarter for a 45-yard pickup to set up a tie-breaking field goal.

Belichick and his staff scrambled to solve a problem in the form of a CFL castoff whom the Seahawks had invited for a tryout the previous winter. The Patriots’ solution—a heavy dose of the 6' 4" Browner—worked, but the Super Bowl’s Cinderella story had seemingly been found.

Bryan Stork still remembers his first day at New England’s rookie mini-camp. As a 2014 fourth-round draft pick of the Patriots—after the team took a quarterback, Jimmy Garoppolo; before they selected a running back, James White—he expected to make the roster. If all went well, he would become the starting center, meaning an NFL legend would become quite familiar with his posterior.

Still, this was New England, where undrafted prospects merit more than cursory looks. There must have been 60 rookies on the practice field that day, Stork estimates, and one in particular caught his attention. He couldn’t stop watching a shorter cornerback from West Alabama by way of Hinds Community College in Mississippi.

Stork had won a national title at Florida State one season earlier; that winter, he had a chance to win back-to-back championships at the college and NFL levels. But as the postseason unfolded, he needed to get back on the field. He sprained his right MCL in New England’s divisional-round win over the Ravens—it didn’t require surgery, but it kept him out of the AFC title game win over Indianapolis. Over the two weeks leading up to the game, he practically lived in the trainer’s room, doing anything possible to speed up the healing of his ailing leg. One morning he bumped into Brady. “Remember: This is your f---ing Super Bowl.”

With Brady’s help, Stork added extra recovery sessions at TB12, the rehabilitation center located just up a hill from the Patriots facility. Brady’s body coach, Alex Guerrero, tended to the injury himself. Stork stretched, strengthened, hydrated, slept. “Eventually, I knew,” he says, “that I was gonna be alright.”

As he returned to practice, he felt Belichick tracking him. “I always had this voice in the back of my head,” he says. “Like everybody was always watching everything I did.”

Stork was sure to soak it all in during Super Bowl week—he even remembers the grass on the University of Phoenix Stadium field was a darker green; he can still picture the stains it left on his cleats. He played all 74 of the Patriots’ offensive snaps, and he provided a crucial, unseen contribution on what ended up being the game’s final scoring play.

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated

Baldwin finally received his first target, which resulted in a 3-yard touchdown and a 24–14 Seahawks lead with 4:54 left in the third. At that point, the Seahawks had shifted back into more zone coverage, their defense worn down by injuries. As the fourth quarter unspooled, Seattle’s lead felt less and less safe, especially when Brady found Danny Amendola for a touchdown. New England trailed by three with 7:55 left.

The Patriots forced a three-and-out and mounted a methodical drive; they faced a second-and-goal from the Seattle 3 as the clock ticked toward the two-minute warning. The play call—Spin X Return, according to Edelman—was one the Patriots had added to the game plan the night before kickoff. The call itself was good, but Stork noticed a problem: The protection Brady set was wrong. It didn’t account for an extra defensive back the Seahawks had lurking in the box.

The rookie, with the outcome of the Super Bowl hanging in the balance, overruled the legend—it’s the first and only time that season that Stork recalls changing a protection scheme. Brady lined up under center and, at the snap, the Seahawks sent seven pass rushers. All of them were accounted for.

As for Edelman, he knew the Patriots hadn’t run this particular play in a single practice. But he also knew the play’s intention, because he was there when Brady and offensive coordinator Josh McDaniels concocted it to take advantage of Edelman’s quickness against Seattle’s forest of tall defensive backs. Edelman, lined up wide left, almost couldn’t believe the setup: He was in single coverage, with the 6' 2" Simon defending him. At the snap he moved right, then cut back left into wide open space on the outside. Touchdown. The Patriots led, 28–24, with 2:02 remaining. Edelman began to think ahead, to another drive, because 122 seconds felt like an eternity.

Lynch couldn’t believe the play call.

No, not that one; this was six plays earlier. After a touchback, the Seahawks’ hopes for a game-winning drive started 80 yards away from the end zone. With an automatic clock stoppage at the two-minute warning two seconds away (plus three timeouts remaining), the entire playbook was available for offensive coordinator Darrell Bevell. He sent a one-word play call, named for Lynch’s home city and designed for the star back to deliver a big play in an unexpected way.

Lynch says the Seahawks had “Oakland” ready for several weeks. They lined up with an empty backfield, Lynch the widest receiver on the formation’s left side. Even when split wide, a running back will typically run a short route—the play design depended on the Patriots anticipating that. With do-it-all linebacker Jamie Collins following Lynch out wide, indicating man coverage, Lynch says the Seahawks had the look they wanted. Russell Wilson took the shotgun snap, and Lynch took a couple of choppy steps, turning inside to run a slant as Ricardo Lockette, aligned in the left slot, headed upfield on a clear-out route.

As soon as Collins took a hard step to play the slant, Lynch executed a sluggo route (the abbreviated jargon for a “slant and go”), driving off his right foot and cutting back outside Collins, heading up the left sideline. Wilson’s throw connected with him 20 yards upfield.

“At that time of the game, that was the last thing that I was expecting to pop off,” Lynch says.

Collins, then one of the league’s most athletic linebackers, caught up and dragged Lynch down, but not until the ball was on the other side of midfield. Soon, however, the final drive’s surprising opening play would be overshadowed, twice.

Kearse sits forward on that black leather couch inside his golf center. He is ready to watch the catch. It’s the one that so many strangers tell him has been lost to Super Bowl history, though he doesn’t think that’s necessarily true (they’re asking him about it, aren’t they?).

On a first-and-10 at New England’s 38, with 1:14 left, Kearse got what he was expecting: man coverage from Butler, who had followed him that night. He flew up the right sideline on an Inside Go route. “It all happened so fast,” he says. Wilson lofted a high spiral. Short, Kearse thought, as he tracked the flight and slowed down ever so slightly around the 15-yard line. As the ball descended he fell backward, entangled with Butler. Butler deflected it as they fell. “It’s broken up again,” began play-by-play man Al Michaels, who then paused for a beat, “and, is it? . . . But, somehow—did he wind up with the football?!” With Kearse spinning on his backside, legs splayed in the air like a break-dancer, the ball had deflected off Butler’s hand, then off Kearse’s left knee. He batted it back into the air with his right hand, batted it a second time, then corralled it as he spun to a stop, hopping to his feet. That was the first time Butler saved the Super Bowl; he scampered to his feet immediately, forcing Kearse out of bounds at the 5-yard line.

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

“I thought of the other catches, David Tyree and Mario Manningham, 100%,” Edelman says, referring to the Super Bowl losses. “Your mind goes to dark spots.”

Like what crossed Stork’s mind: Are we jinxed?

“And then we run a Weak,” Lynch says of the next play, a run up the middle to the weak side of the defense. “And, s---, I probably should have gotten in.” Instead, linebacker Dont’a Hightower caught Lynch’s foot, tripping him up a yard short of the goal line.

Kearse continues staring at his iPhone, eyes tracking a clip he’d rather erase. On the screen, he is lined up on the right side of the formation, next to but just in front of Lockette, as one-half of a Twin Stack. He was 2 yards from the end zone. Two yards—and some 30 seconds of game clock—from a second-straight championship.

The play call—“Halo,” a rub-route slant concept—struck him as no more than mildly unusual, at least back then. Still, like the 70,000-plus fans packed into University of Phoenix Stadium and a TV audience numbering well into the millions, he was expecting another handoff, the obvious call. “In your mind, there’s a part of your subconscious that figures we’re just gonna give the ball to him again,” Kearse says.

Seattle’s offense seemed confused. As a course correction, Wilson motioned Baldwin left. Browner stood in front of Kearse, his former teammate in Seattle. Butler crouched behind Browner, to his left. Kearse knew that defenses generally defend stacks in two ways. Because of an earlier swap, he expected Browner to shift inside, toward Lockette’s slant, meaning that Butler would stay with him. “Malcolm has been following me the whole time,” he says.

Lynch recalls excitement in the Seahawks’ offensive huddle. “Everybody had the thought, like, we was gonna run the exact same play again.” After getting the call and breaking the huddle, Lynch remembers lining up on the wrong side of the formation (“I was so discombobulated”). Then he remembers doing … nothing.

Edelman believes he understands what sustained those Patriots. He sees a “mentally tough team that performs well under pressure.” The Seahawks dialed up a play similar to the one the Patriots’ offensive scout team kept destroying the first-team defense with during practice. Butler didn’t stay on Kearse. He switched, shooting right toward Lockette. Kearse ended up blocking Browner instead, and, when he couldn’t move Browner into Butler’s path, Butler jumped the route.

John Iacono/Sports Illustrated

“Malcolm made the play of his life,” says Kearse. “They could have collided. The ball could have dropped, or bounced up. Anything could have happened. But he made the play. Nothing but respect for him.”

Adds Brady, in an emailed response for this story: “Malcolm made one of the great interceptions in the history of any Super Bowl. He truly [saved] the game for us.”

But what if he didn’t? Most Seahawks have certainly considered an alternate universe in which they won the game; a few Patriots players have too. Are the Seahawks the dynasty in this scenario? Do they stay together and keep winning? Does Brady retain the desire necessary to play football while approaching A.A.R.P.-membership age?

At the beginning of that season, the 15th of Tom Brady’s career, he was not known as the GOAT or for his recovery pajamas or avocado ice cream habit.

Throughout training camp that season, his mind kept returning to the same word: perspective. He won three titles in his first four years as a starter. But his most recent Super Bowl appearances were losses to the Giants, the 2008 and ’12 seasons. New England’s last title was won by the ’04 team. In August ’14 Brady turned 37; pundits and analysts were prepared for the twilight of his career.

“You realize how hard it is to win one,” Brady says. “And two losses make you appreciate it so much more.”

At the Patriots victory party, Edelman ran on euphoria culled from his first title. He hopped onstage to rap alongside Rick Ross, downed a shot of Jack Daniels with Belichick and hung with Jon Bon Jovi. Stork brought his family to the festivities, along with a close friend from Florida State who got so drunk he tried to get into it with Rob Gronkowski. By night’s end, Stork would puke-and-rally, and Edelman would remove his shirt.

Brady remembers the XLIX postgame, celebrating with his teammates before decamping to his private party, where the mood was more subdued. He sipped a vodka soda surrounded by maybe a dozen friends and family members. He didn’t say much. Still, “it was magical,” he says.

When he looks back on that season, he remembers the battles. To endure Deflategate, which began with accusations by the Colts following their blowout loss to New England in the AFC championship game. To get to the Super Bowl and to win the game itself. “Win or lose, that will bring you together in ways that not playing in the Super Bowl never would,” he says. Edelman agrees and believes that the game helped launch the second chapter of the Patriots’ dynasty, resulting in Super Bowl victories two and four years later. “It propelled our generation of Patriots,” he says.

The Seahawks, meanwhile, were stunned but never silent. In the post–Super Bowl locker room, Lynch took swigs from a bottle of Hennessy and called out, “These motherf-----s robbed me!” Carroll didn’t help matters upon the team’s return to Seattle. He gathered the Seahawks for their typical exit meeting. Most of the veterans expected him to assume the kind of accountability he demands from the players, to say the staff made a mistake with that final play call, to admit they should have run the ball. Instead, as one player describes it, “he doubled down.”

After Carroll’s address, some who heard it gathered in small groups to lament the speech. Conspiracy theories surfaced: Did Carroll want to throw so that Wilson would win Super Bowl MVP rather than Lynch? Some Seahawks truly believe that. That game, and the way it ended, still eats at their insides.

Says Lynch: “What we had before was a belief system. The belief system was tarnished after that.

The Seahawks’ core mostly stayed together for the next few seasons, but they failed to advance past the divisional round in 2015 and ’16 and missed the playoffs altogether in ’17. By the ’18 season—the year the Patriots won their sixth and final title with Brady under center—Bennett, Richard Sherman, Lane, Kam Chancellor and Cliff Avril were retired or playing elsewhere. Lynch had signed with his hometown Raiders before the ’17 season, while Kearse joined the Jets. Matthews declined a practice squad demotion in ’15 and was released.

Players from that Patriots team wonder whether a loss would have splintered them in a similar fashion. Would Brady become late-career Brady without the win that broke his Super Bowl drought? New England played in three of the next four Super Bowls, winning two of them. Edelman was there for those three rings, and he credits his current life to that night in Arizona. “Everything,” he says, “started right there.”

The podcast that Edelman hosts with Morril is called Games With Names, and its mission is singular: to determine the greatest game ever played, in any athletic event. Contenders for that lofty perch include Ricky Williams setting the single-game rushing record at Texas (’98), the U.S. Women’s National Team’s triumph in the World Cup Final (’99), and the WWE’s “Iron Man Match” between Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels (1996).

Edelman says he isn’t sure whether XLIX would qualify for the top spot. But he knows who the guest would be on that episode: Lynch, of course.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Two years after Super Bowl XLIX, at a coaching clinic, Matt Patricia, the Patriots’ defensive coordinator for that game, told New England’s side of the game-defining play.

The Patriots had run out a never-before-seen personnel combination, which surely fed into the confusion on the Seattle sideline and in the huddle. Along with three cornerbacks to match up with the Seahawks’ three receivers, New England had stacked the line with four 300-plus-pound linemen: Vince Wilfork, Sealver Siliga, Alan Branch and Chris Jones.

“Great running back,” Patricia said at the clinic. “We’re going to force [Seattle] to throw. I’ve got 3,000 pounds of flesh up to the right-hand side of the defense, all right? They’re not going to run Lynch right into that.”

Lynch recognizes the appeal of the counterintuitive play call and is aware of the Patriots’ supersized front. He still insists he would have scored, just like he did against New England’s lighter goal-line personnel earlier in the game, just like he did so many times throughout his career.

Now 36, many of Lynch’s current pursuits started while he was playing football, whether investing in the community of his hometown, Oakland, running youth football teams or making cameos in television shows and movies. More recently, Lynch created a scholarship as part of his Fam 1st Family Foundation to send 10 middle schoolers to summer camp at IMG Academy. After expanding his acting chops with a small role in Season 3 of HBO’s sci-fi series Westworld a few years ago, he took his first major role in a full-length feature film, Bottoms, a teen sex comedy set to premiere at the SXSW Festival in March (synopsis, according to IMDB: “Two unpopular queer high school students start a fight club to have sex before graduation”). He even started opening restaurants. His latest: a Hawaiian/Korean fusion spot, Beastro, by Marshawn Lynch, in Portland.

He spends his time worrying about kids—specifically, the dangers of social media, mental health, depression and anxiety, the cauldron that today’s teenagers grow up in. He checks in with students he knows, about their grades and class attendance. He makes sure they stay in school. And he tells them what he learned, including what The Handoff That Never Happened reinforced about a lesson his mom taught him years ago.

As Lynch tells it, in his first Pop Warner football game he played offensive line for the Oakland Saints. After a loss, Lynch beelined to his mother, Delisa. “I was so dedicated to this s--- that after the game, I came over to her, and I was crying.” She looked at him sideways. “Boy,” Lynch remembers, “if your ass stop crying, you get to do this s--- again next week.

“[Regarding the Super Bowl], it was like, I could bitch and moan and cuss motherf-----s out. But it was more like I had to remember the s--- that I stood on. My morals. My values. My principals and s---.”

He says, wine-flavored cigar in hand, he believes that lesson is a big reason why, despite the rest of the world’s reaction to the ball he never got, “I probably don’t take it as hard.”