When the National Weather Service (NWS) tweeted out a rare tornado emergency for parts of the state of Mississippi last Friday evening, it was the final step in a series of warning systems that forecasters use to predict storms and, crucially, help people on the ground understand any danger to their well-being.

And the danger, in this case, was sky-high. An elevated version of tornado warnings, tornado emergencies are only issued when a “severe threat to human life is imminent or ongoing.” Ultimately, the long-track tornado — a storm that lingers on the ground for a longer period of time than normal — cut a 59-mile path across Alabama and Mississippi, killing at least 26 people, with the majority-Black town of Rolling Fork, Mississippi particularly hard hit.

But meteorologists at the NWS and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Storm Prediction Center would have known a few days in advance of a storm front advancing on the broader Southeast region. Adam Houston, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, tells Inverse that the storm that produced the tornado was a “well-forecasted” event.

But this brings up a few questions: If meteorologists had advance warning, why did so many residents still fall in harm’s way? That’s a difficult question to answer, but it hinges on two interrelated factors: the science of tornado forecasting and the communication of natural disaster threats.

How do we detect tornadoes?

There are two ways we primarily detect tornadoes. First: storm spotters — which can be emergency managers or local tornado chasers trained by the NWS to recognize storms — report visual confirmation of a tornado.

The second method uses radar and can get a little scientifically complicated, so we asked Houston to break it down for us. (Houston was conducting fieldwork with his students in Mississippi at the time of the Rolling Fork tornado).

Tornado detection technology has significantly improved since the days of the 1996 movie Twister. Around the same time, NWS switched to using the Doppler radar, which allowed scientists to scan the depth of a storm and detect the motion of precipitation in tornadoes. For the first time, scientists were able to detect velocity in a storm — a game-changer for understanding and predicting tornadoes with greater accuracy.

The Doppler radar can help scientists pinpoint signs of a vortex rotation in a storm, also known as a Tornado Vortex Signature — a radar pattern that indicates intense rotation in a storm and appears several kilometers above the ground before a tornado touches down, according to NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory. It’s not a guarantee a tornado will manifest — false alarms do happen — but serves as a clear warning of a potential danger nonetheless.

“We can predict the approximate area where conditions are favorable, but can't yet predict exact locations that will get hit by a tornado,” Crystal Egger, president of Monarch Weather, tells Inverse. Monarch is a group of meteorologists that consults on meteorological and climate services across sectors, whether agriculture, pension funds, or hospitality, among others.

Currently, computer algorithms analyze the Doppler radar for meteorologists, making it easier to interpret the data coming from it and reducing the false alarm rate for tornadoes. Scientists also run numerical weather prediction models — basically, computer simulations — to identify atmospheric changes that are more likely to lead to tornadoes.

“Without question — over the last few decades — our understanding of how to interpret Doppler radar has improved,” Houston says.

How far in advance do we know a tornado will hit?

There are different timescales when it comes to forecasting tornadoes, Houston says. They include:

Days out from the storm

A few days in advance, weather patterns can hint that conditions are favorable to form a tornado. NOAA spokesperson Keli Pirtle tells Inverse that the agency’s Storm Prediction Center knew conditions were right for tornado formation in Alabama and Mississippi a few days ahead of the tornado hitting the ground in Rolling Fork.

But accuracy of storm prediction may look different to a meteorologist than to a non-scientist. Houston explains that at this point, scientists can’t say with any certainty how many storms will form, where exactly tornados will strike in these states, or whether they will manifest with 100 percent certainty. All they know is there is a strong likelihood of tornado-producing storms in this general region.

“No one with any legitimacy predicted that Rolling Fork would get hit by a tornado, and several days out, or even a day out,” Houston says, adding that people in the area knew there was a “threat” of a dangerous storm that could impact their region.

Hours out from the storm

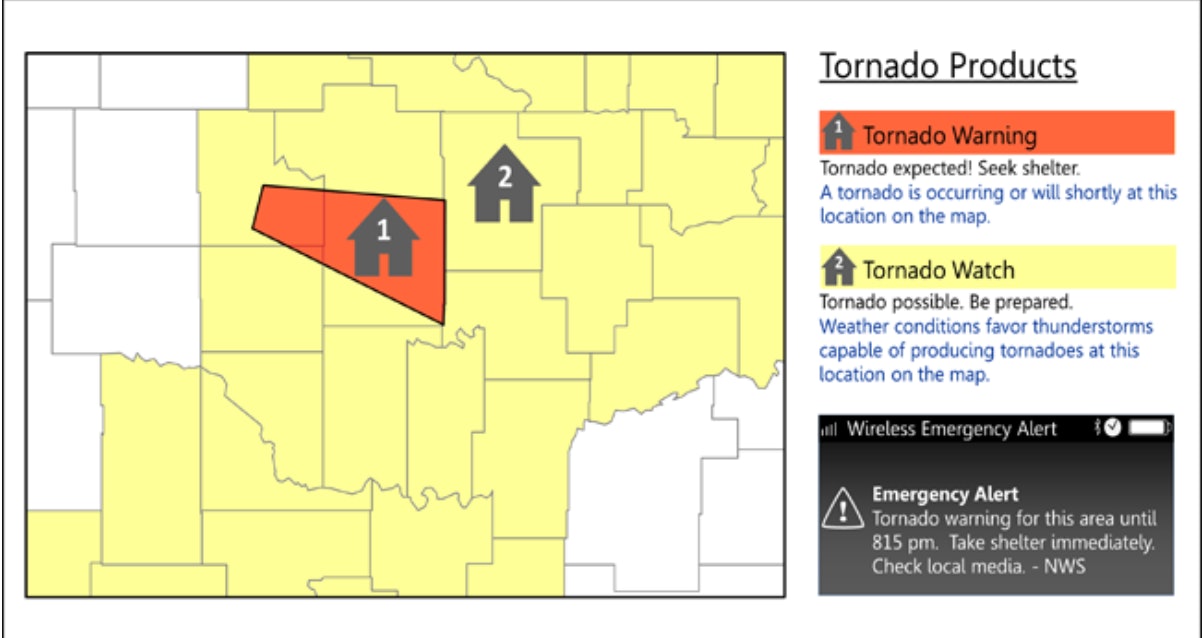

As the day of the tornado approaches, the precision of the forecast gets a little better. At this point, meteorologists can hone in on a particular region likely to be impacted by a storm. NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center will typically issue a tornado watch for the region around four to six hours in advance. A tornado watch indicates that tornadoes are possible and residents should begin making emergency preparations.

At this point, residents in affected areas may hear about the tornado watch through different channels of communication. A 2018 study explains the common ways people receive information about tornados:

- NWS radios

- Social media and news outlets

- Local TV weather channels

- Smartphone alerts

- Friends and family

- Tornado sirens

Minutes before the tornado hit the ground

Finally, once a tornado has been formally detected through radar — and sometimes visual confirmation — the local weather forecast office issues a tornado warning to towns and cities directly in the path of the tornado. This takes place about 15 minutes out, Houston says.

At this point in time, residents in Rolling Fork or other affected areas would receive a tornado warning. If they have smartphones that are set up to receive wireless emergency alerts, they would get a warning notification on their phone. City or county officials are also supposed to activate a blaring tornado siren to alert residents as a final measure — but people in Rolling Fork said they didn’t hear any siren.

Why was Rolling Fork so badly hit?

But forecasting and emergency warnings alone can’t fully explain what happened in Rolling Fork. There were other factors that made the tragedy in the Mississippi town more likely.

First: the tornado started Friday evening, continuing overnight into Saturday. This placed it at a time when many people are sleeping and don’t see alerts for tornado warnings. Residents may also be driving home from work in the early evening and can’t seek safety, even if they do receive a tornado warning on their phone or over the radio.

According to a 2008 study, nighttime tornadoes are 2.5 times as likely as daytime tornadoes to result in death. This makes nocturnal tornadoes challenging, “not so much to forecast as much as it is to get people to respond with a warning,” Houston explains. This time also makes visual identification hard, and scientists have to rely solely on radar to detect tornados, which people on the ground may not take as seriously.

Second: Many in Rolling Fork live below the federal poverty line, making them especially vulnerable to natural disasters since they’re more likely to live in mobile homes or similar dwellings instead of more permanent structures that are more able to protect people from natural disasters. Roughly 30 percent of Sharkey County residents live in such housing.

Normally, if a tornado is approaching, you’d either seek shelter in the basement or find an interior room of your house or apartment away from windows if there is no basement. Neither of these is an option for people living in mobile homes.

“If you’re in a mobile home, there is no safe place,” Houston says.

This also highlights the pervasive role of economic vulnerability and disaster risk. Kim Klockow McClain, a research scientist and lead of the Behavioral Insights Unit with the NOAA National Severe Storms Lab, tells Inverse, “We often say that the impacts of disasters fall heaviest on the shoulders of those who can least deal with it.”

Finally, Egger says that meteorologists have observed an increasing frequency of tornadoes in recent years in states like Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Although scientists aren’t certain about the role of climate change in tornado production, some experts suggest climate change could be impacting where and how often tornadoes hit the ground.

Since these states are located outside of Tornado Alley — a belt of states including Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska where the most tornadoes typically occur — residents in these areas may be less prepared to deal with tornadoes.

“Unfortunately, increases in tornado frequency in the American South juxtapose with a population that is especially vulnerable to tornadoes,” Egger adds.

What next-generation technology will help?

Individuals can and should prepare for tornadoes by keeping an eye out for potential tornado watches or NWS emergency warnings in their area. The NWS also has a guide for best practices on what to do during a tornado. McClain says community organizations can also organize phone trees and make plans in advance to get vulnerable residents — like the elderly or individuals with disabilities — to safety.

But on the science front, meteorologists are also banking on improvements in weather forecasting to improve tornado prediction — and, hopefully, save lives in the long run.

Egger explains to Inverse that technology known as dual-polarization radar or “dual pole” has “revolutionized” our ability to track tornadoes on radar. It’s essentially a form of radar that transmits and receives pulses in a novel way. The radar frequencies from these pulses can help better detect the size of targets being observed — such as tornado debris.

“This technology can detect non-meteorological particles in the atmosphere, such as debris being lifted by a tornado,” Egger says.

While Doppler radar has come a long way since it debuted in the 1990s, it still isn’t great at predicting the nature of individual storms days in advance. Gaps in radar data also hinder our ability to predict storms.

“While we are fortunate to have an extensive network of Doppler radar sites in the U.S., there are still some gaps in radar coverage, especially at low levels of the atmosphere,” Egger says.

But Houston says technological advancements could help us get better at predicting tornadoes in the next decade. The Warn-on forecasting system — a NOAA research project that tries to increase the lead time for tornadoes, thunderstorms, and flash floods — could give us more advance notice in predicting individual storms in the coming years.

“They’re using these models to actually attempt to predict the future state of an individual storm. And so that’s a huge advancement and it’s been many, many years in the making,” Houston says.