After nearly two months of hostilities between the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Hezbollah in Lebanon, the two sides have agreed a 60-day ceasefire, allowing many of the civilians who have been forced to flee the fighting in south Lebanon to return to their homes.

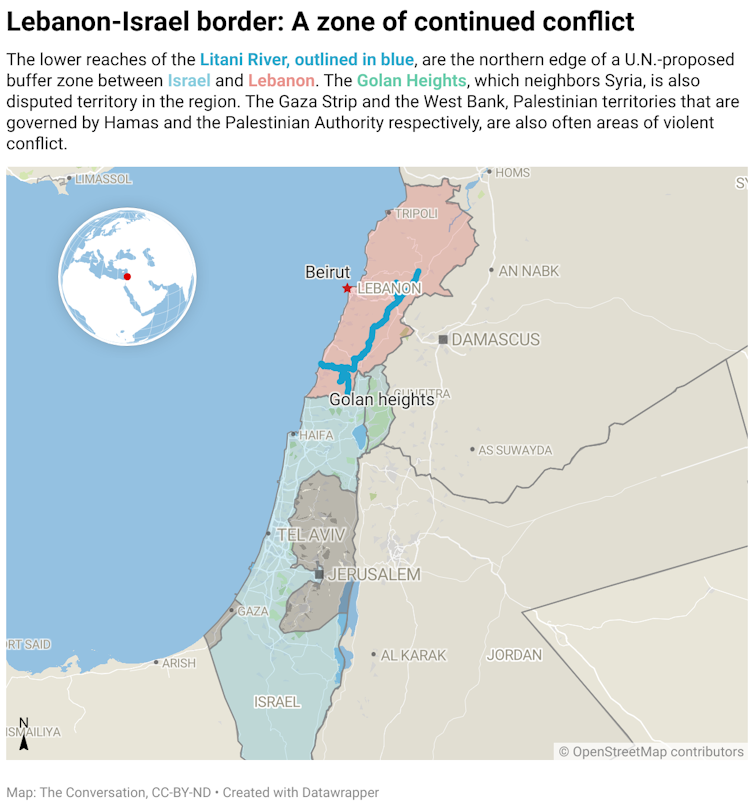

The terms of the deal are very similar to the situation after Israel and Hezbollah last came seriously to blows in 2006. Israeli troops are to withdraw back across the border into their own country. Hezbollah, meanwhile, will withdraw all of its fighters from the region south of the Litani river, the old “blue line” boundary which was set by the United Nations in 2000 and aimed to create a buffer zone between Israel and Lebanon policed by UN peacekeepers.

But given that this has failed to keep the peace in the past, what are the prospects of it holding now? John Strawson, an expert in Middle Eastern politics at the University of East London, addresses some of the key issues.

Has Israel successfully neutered Hezbollah?

Israel will count its 2024 war against Hezbollah as a major success. The IDF had been planning for it since the end of the 2006 war which resulted in major Israeli casualties while failing to seriously weaken Hezbollah.

It is evident that Israel had excellent intelligence this time and had the ability to act on it – that much was already clear from the operation, a few days before Israeli troops crossed into southern Lebanon, in which it exploded pagers and walkie talkies. In two months of conflict, it has managed to eliminate Hezbollah’s top leadership, including Hassan Nasrallah. It has destroyed numerous military sites near the Israeli border and degraded much of Hezbollah’s stockpiles of weapons, including strategic missiles.

Israel’s land operation has been much more successful than many commentators (including myself) thought it would be – and there have been fewer casualties than in 2006.

But I wouldn’t say that Hezbollah is neutered, as even after two months and all these Israeli gains, it was still able to fire between 200 and 250 missiles at Israel last weekend – and in the last week of the war it even forced Ben Gurion airport in Tel Aviv to suspend operations.

But Hezbollah is not the organisation it was on October 8 2023, when it began attacking Israel in support of the Hamas atrocities the previous day. The fact that it has entered a ceasefire with Israel before the end of the Gaza war underlines that its diminished military capacity is reflected in its more modest political goals.

What is Israel’s war aim in Gaza now?

Benjamin Netanyahu’s major achievement with the ceasefire is the detaching the Gaza war from Lebanese front. This he sees at an important breach in the Iranian “axis of resistance”. The Israeli prime minister is now faced with major choices over the war in Gaza. He has always maintained that his aim is total victory over Hamas – and in the ceasefire with Hezbollah, Netanyahu has perhaps shown that his “total victory” goal is entirely dependent on his definition of what that means.

Essentially, Hamas has pretty much been defeated and its leadership decimated. I believe it would be quite incapable of mounting another October 7 style operation. Its weapons supplies are diminished, and its forces are disorganised. That does not mean it is unable to engage in the guerrilla tactics that are still killing Israeli forces, but it will also be feeling more isolated after the Hezbollah ceasefire.

Hamas leaders both inside Gaza and outside – mostly in Turkey these days, since Qatar bowed out of its role in peace talks – will question the resolve of Tehran, especially as it has welcomed the ceasefire.

Egypt has launched a new plan for a more limited ceasefire in Gaza. It would be for one or two months based on a reduction of Israeli military activity, a phased return of some hostages and an increase in aid with the reopening of the Rafah crossing between Egypt and Gaza. It does not provide for an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza.

This initiative has not only been coordinated with the current US administration but apparently Egypt has also been in contact with Donald Trump. Hamas might have to accept the new reality that it is on its own.

This deal might well appeal to Netanyahu as it leaves his options open about the longer-term future of Gaza.

How does Trump’s re-election play into all this?

The Egyptian government’s contact with the incoming Trump administration is undoubtedly intended to put pressure on the Israelis. The strongman Egyptian president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, was one of the first leaders to congratulate the US president-elect and his voice will certainly carry more weight in a Trump-led White House than under Joe Biden.

But whether Trump will support Egypt’s plan is unclear. The newly re-elected US president wants to be seen as the big backer of Israel. But at the same time he would love to go down in history as the man who brought peace to the Middle East. And, as we know, he professes himself to be against “forever wars”.

I suspect Trump’s backing of Israel is more connected to his strategic concerns over Iran’s nuclear program than his affection for the Jewish state. It might well be in his interests to take office with ceasefires in place in both Lebanon and Gaza, so that he can focus on Iran.

Are the Abraham Accords back on the agenda?

It is a remarkable fact that despite the 13 months of war, the key states of the accords have maintained their relations with Israel. It is also the case that the US-Saudi talks over energy and strategy have continued to include the possibility of the Saudis recognising Israeli statehood.

The accords were one of the big foreign policy initiatives of the first Trump administration. Israel signed deals to normalise relations with UEA, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan. Saudi Arabia was expected to be among the Arab states who would follow suit – and the Biden administration made strenuous efforts to ensure that it would. But the October 7 Hamas attack and the conflict that followed have (temporarily at least) put paid to that.

But Trump’s warm relations with the Saudis during his first term are likely to be renewed after he takes office on January 20. It’s quite possible that if a peace deal could be cut in Gaza, we could see developments on this issue, which would leave Iran seriously isolated in the region.

John Strawson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.