On Friday, the Federal Court dismissed Ben Roberts-Smith’s defamation case against The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Canberra Times.

Justice Anthony Besanko ruled the newspapers had established, by the “balance of probabilities” (the standard of evidence in a civil lawsuit), that Roberts-Smith had committed war crimes.

Following the ruling, much public debate has focused on what the Australian War Memorial should do with Robert-Smith’s uniform, helmet and other artefacts of his on display.

Greens senator David Shoebridge called for the removal of these objects from public display to correct the official record and “to begin telling the entire truth of Australia’s involvement in that brutal war.”

The topic of what to do with Roberts-Smith’s uniform and helmet was debated on ABC’s Insiders yesterday: should the display be removed, effectively cancelled, or changed to tell the full story?

Read more: 'Dismissed': legal experts explain the judgment in the Ben Roberts-Smith defamation case

The case of the oil paintings

It is not just these artefacts on display. The memorial also has two heroic oil painting portraits of Roberts-Smith by one of Australia’s leading artists, Michael Zavros.

These paintings were commissioned by the memorial in 2014.

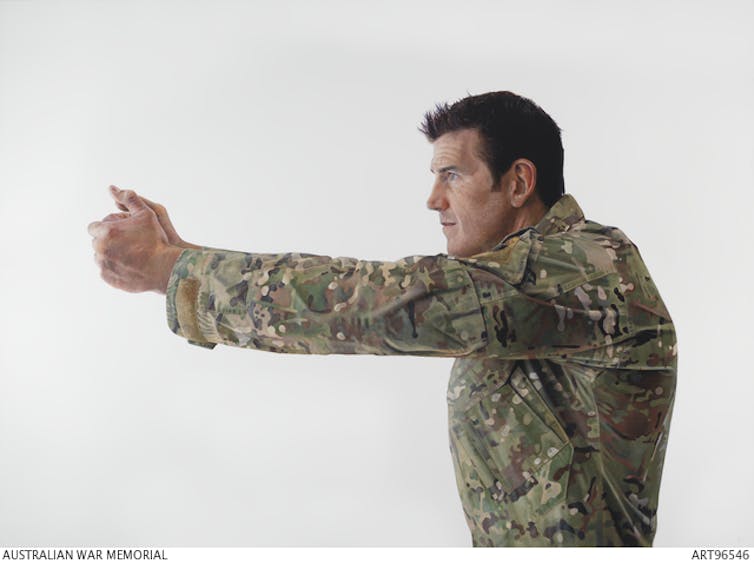

Pistol Grip (Ben Roberts-Smith VC) is a larger-than-life-sized depiction of Roberts-Smith, camouflage arms outstretched, mimicking the action of holding a pistol.

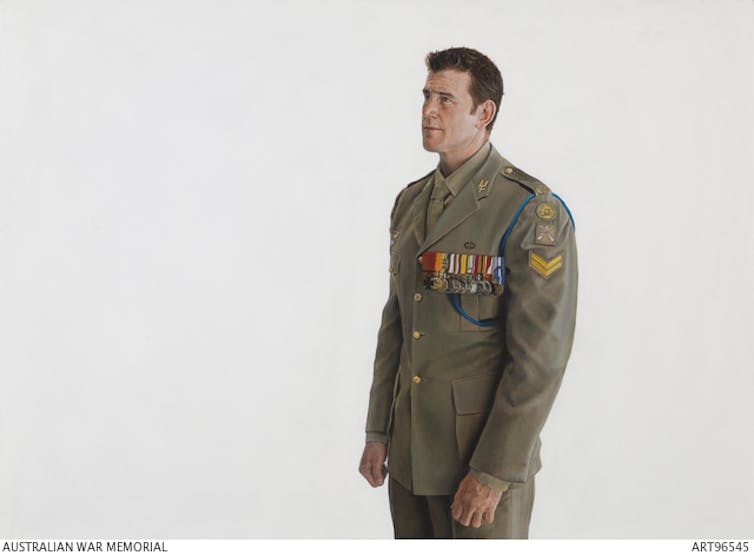

The smaller Ben Roberts-Smith VC depicts him in ceremonial military uniform.

In an article in arts criticism website Memo yesterday, respected Monash University art historian Rex Butler and arts journalist Paris Lettau weighed into the debate.

Butler and Lettau say Pistol Grip is:

threatening, over-bearing, macho, hyper-masculine, celebratory, and enormous, like the man himself – some 220 centimetres wide and 160 centimetres high.

When Zavros created his large portrait it was a depiction of a soldier doing what he was trained – and venerated – for doing.

It is an aggressive pose that, given current developments, can be read in a much more sinister way. It touches on a far bigger question of how national institutions for the public memory of war address difficult and morally ambiguous moments in a national story.

Moral and ethical ambiguity

When the Canadian War Museum opened at its new site in Ottawa in 2005, its new displays included two paintings in their collection by Canadian artist Gertrude Kearns.

The paintings, Somalia without Conscience, 1996, and The Dilemma of Kyle Brown: Paradox in the Beyond, 1995, dealt with one of the most shameful episodes in Canada’s military history, known as the Somalia Affair.

In 1992, the Canadian Airborne Regiment was deployed as peacekeepers to Somalia. In 1993, 16-year-old Shidane Arone was found hiding in the Canadian base, believed to have been stealing supplies. He was tortured, and soldiers photographed themselves with the semi-conscious boy. Master Corporal Clayton Matchee and his subordinate Private Kyle Brown were charged with his murder and torture.

Somalia without Conscience depicts Matchee posing with the beaten Arone, while The Dilemma of Kyle Brown depicts Brown symbolically holding two potential fates in his hands: a lightly coloured cube in his right hand, and a darkened cube in his left. It addresses an ethical grey area many soldiers face during active service when the hierarchy of command comes into direct conflict with conscience.

Following the opening of the new Canadian War Museum, the presence of Kearns’s paintings sparked intense debate. Curator Laura Brandon received abusive emails from members of the public.

The museum copped criticism from figures such as the head of the National Council of Veterans Associations, who called the paintings a “trashy, insulting tribute” and urged a boycott of the opening of the new museum.

Discussing this controversy in 2007, Brandon said what upset veteran communities was that “their” museum:

was not only telling the stories of heroism and courage that most of them expected to be told but also stories about failures, disappointments, and human frailty.

Brandon remained steadfast the museum needed to address the messy ambiguities of war and, despite pressure, kept Kearns’s paintings on display for the duration of the exhibition.

The complexity of contemporary art

Brandon’s curatorial decision to display Kearns’s Somalia paintings strike at the heart of what is special and important about contemporary war art in a national museum.

Contemporary art presents ethical and moral complexity, grey zones and a range of perspectives. This is vital in a healthy liberal democracy.

While Brandon’s choice to show Kearns’s Somalia paintings attracted criticism, the museum remained committed to telling a story that is difficult, ethically and morally complex, and uncomfortable for Canadians.

To remove Zavros’ portraits from display would remove the now-untenable hero narrative that once surrounded Roberts-Smith. But doing so would also rewrite public memory by effectively erasing an important part of why and how Roberts-Smith was revered.

These portraits now represent a morally complex story that needs to be addressed by our national war museum.

To remove the portraits would miss a valuable opportunity to debate important questions about how we construct hero stories.

So, how could these portraits still be shown in future?

Zavros’ portraits were already complex works.

Following Friday’s announcement, it is more important they are seen in all their additional multi-layered and problematic complexity.

The portraits show us how we create the nation through the stories we tell ourselves, and how dynamic that narrative can be. The portraits present a valuable opportunity to show narratives of war – like the stories of our own lives – are never simple, consistent and coherent.

The portraits should be displayed in ways that address this complexity, capturing the evolving story of Roberts-Smith in explanatory wall text. There is an opportunity here to not simply “correct” the official record, as Shoebridge suggests, but to have a deeper conversation about the role of hero narratives in diverting attention away from more important public debates about Australia’s involvements in conflicts.

Maybe this could be addressed in the art the memorial commissions in future.

The most compelling contemporary art works – and the most valuable museum displays in our national institutions – are those that consider our complex stories, raise important and self-reflective questions, and challenge simplistic narratives.

Prof Kit Messham-Muir is the lead Chief Investigator on the ARC Linkage Project Art in conflict: transforming contemporary art at Australian War Memorial, in partnership with the Australian War Memorial and National Trust (NSW), leading a team of investigators from University of Melbourne, UNSW and University of Manchester. Art in Conflict was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council. Art in Conflict (LP170100039) received a Linkage Project grant of $293,380 and in-kind contributions from the Australian War Memorial. Former Canadian War Museum Curator Laura Brandon was a keynote speaker at the War, Art and Visual Culture: Los Angeles symposium in 2019, as part of the Art in Conflict project. The opinions expresssed here do not in any way reflect those of the Australian War Memorial.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.