SYNTH WEEK 2024: Much like vinyl, ‘analogue’ technology is held in high esteem, but debate rages around the realities of its lauded properties. More than 50 years after the first mass market analogue synthesiser hit the market, their basic format is more widespread than ever.

Do analogue synths really sound better? What makes this theoretically outdated tech remain so popular in the supposedly forward-thinking realm of electronic music making?

There are certain things that only software and digital synthesisers can do, such as complex frequency modulation, granular or wavetable synthesis. In theory at least, there’s little an analogue synth can do that can’t be replicated in the digital realm.

Countless virtual analogue instruments offer exact replicas of classic synth engines, often offering extra convenience through increased voice counts, full parameter recall and – in hardware – a more convenient form factor. So why would anybody want to bother with an analogue synth?

They sound better! I continually have artists telling me how good they sound. They are also much more fun and interactive to play; they feel like a musical instrument should

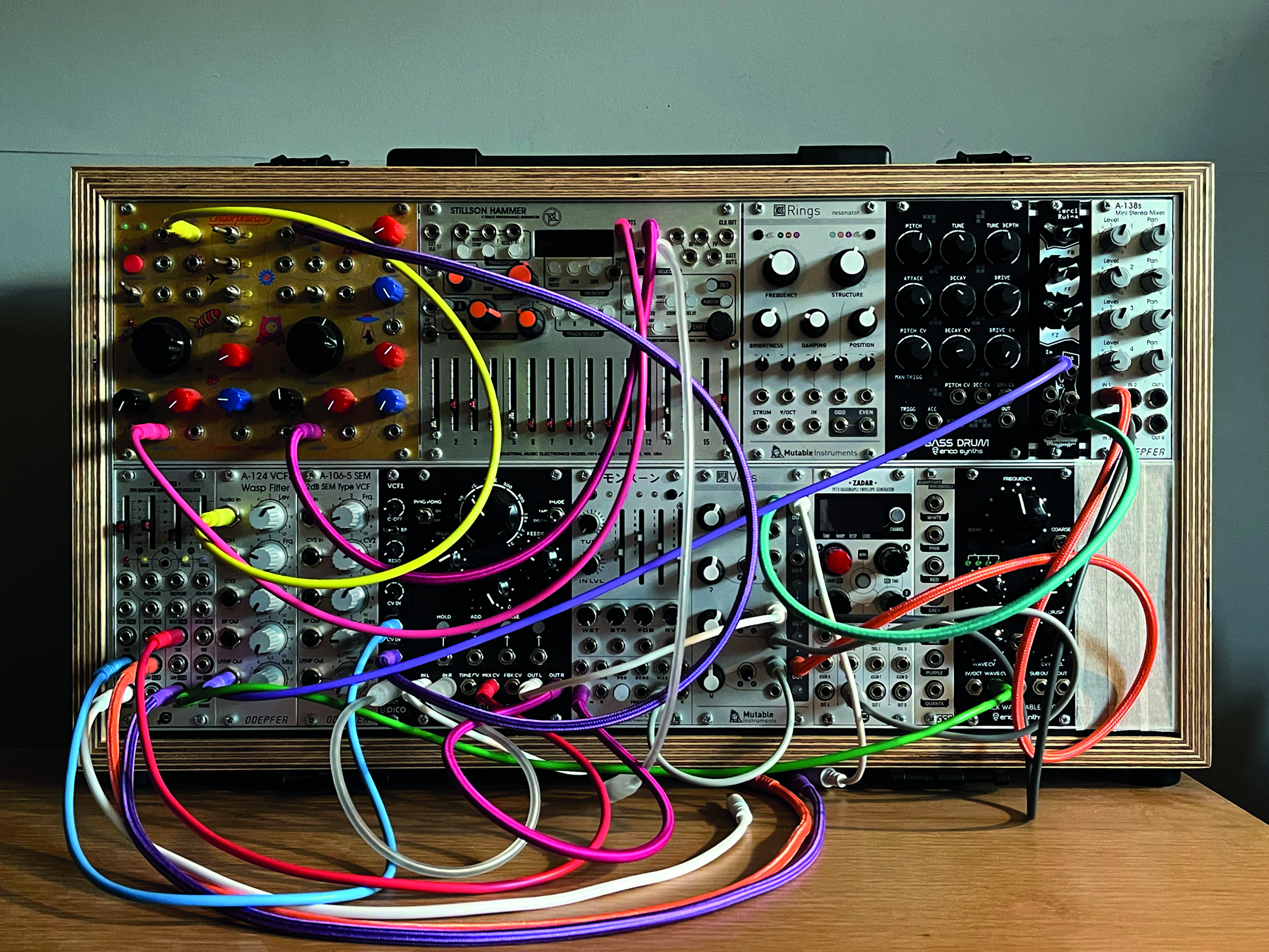

The reality, of course, isn’t quite so simple. Analogue synths are still prized by a multitude of electronic musicians. In fact, with the rise of affordable analogue instruments and Eurorack modular synthesis has meant that true analogue synths have become considerably more accessible and widespread over the past decade.

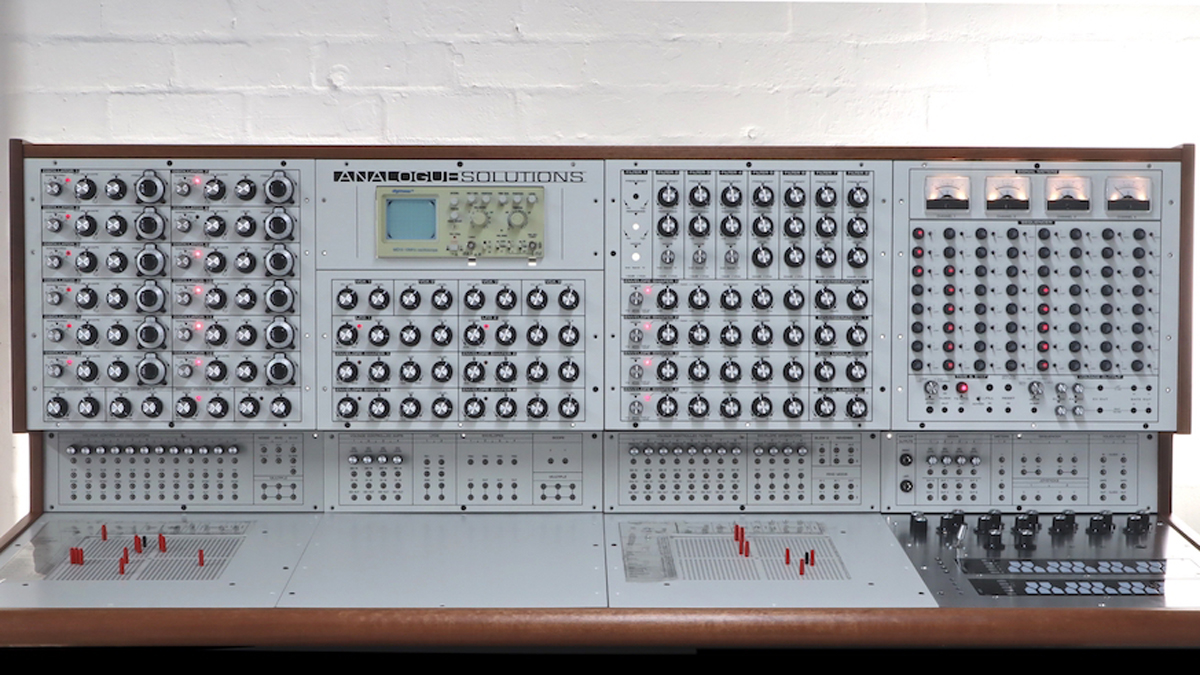

We put the question of analogue’s longevity to synth designer/aficionado Tom Carpenter, of UK brand Analogue Solutions. “Imagine painting a picture, but your easel is at the end of a long hallway and you have to manipulate the brush from outside, via the letterbox, using some very long tweezers,” he explains, when asked about his adversity to software synths. “Many physical digital hardware synths aren’t much better either. For me, if I have to go even one layer down in a menu then that’s me done.”

This physicality is something that is regularly cited as a primary draw of analogue synths. While digital hardware, obviously, also offers an element of hands-on interactivity, the tacticity of adjusting knobs and faders on a voltage-controlled instrument can be difficult to emulate. This becomes ever more true in the semi-modular and modular realms, where physically patching control voltages (CV) provides not only hands-on interaction, but an element of unpredictability. CV signals can create ‘happy accidents’ in a way unlikely to happen in digital synths.

I’d much rather be in front of a hardware synth with a set of knobs that never change or move. It’s all about interacting with a real musical instrument

When it comes to analogue synth design, few can match the career of the late, great Dave Smith. His original Sequential Circuits brand was responsible for some of the most influential instruments of the ’70s and ’80s, such as the Pro One and Prophet-5, and after re-entering the market with Dave Smith Instruments in 2005 (later renamed Sequential) he also created some of the most lauded synths of the 21st century. For him, the draw of analogue all came down to the sonics.

“They sound better!” he once told us. “I continually have artists telling me how good they sound. They are also much more fun and interactive to play; they feel like a musical instrument should. I could talk about all the subtleties of analogue circuitry, but just use your ears.”

While Analogue Solutions has, as the brand name suggests, stuck fairly rigidly to analogue circuitry in the design of their synths, Smith’s DSI and Sequential brands dabbled in digital technology on a number of occasions. In the late-’00s Dave Smith Instruments began equipping synths with DCOs – digitally controlled oscillators that offered analogue sound with more stable tuning.

The Prophet-6 went further with the inclusion of a full wavetable oscillator and digital synth engine. When we spoke to him a few years ago, we asked Smith if he believed in a perfect ‘middle ground’ where digital elements can sit alongside analogue.

The first generation was Bob Moog and Donald Buchla, but here we are and the synths are back, thanks largely to the dance producer folks

“Certainly. Technology has come a long way since I designed the Prophet-5 in 1977,” he explained. “We take advantage of that. The sweet spot depends on the instrument design. Sometimes we use a digital oscillator or wavetable oscillator, sometimes VCOs, sometimes a mix. The most critical part is the filter; we always use analogue filters. Other controls like modulation, LFOs, and envelopes are best done digitally these days, for many reasons.”

Fall and rise

The consensus on analogue synths hasn’t been a constant over the past 50 years though, as another synth design icon, Tom Oberheim, explained to us in 2019. “Dave Smith’s Sequential Circuits went under in 1986 and by then I knew Roger Linn really well and his first company went under. Everything was turning digital. The Yamaha DX7 started the digital revolution in 1983 and then there was the Korg M1 and the Roland D50, so analogue became pretty much dead.

“It became a different world, people wanted perfect strings, perfect brass and a Fender Rhodes that didn’t weigh 200 pounds.” Oberheim credits modern dance music and the Eurorack community as the biggest promoters of the analogue revival.

“Two things happened when the new century arrived. Dave Smith got back in the business in 2005, but the other thing was this growing monster called Eurorack. Thanks to the dance crowd and the Eurorack crowd, analogue is back and better than ever. It was a bumpy ride for someone like me who had been so involved. I was the second generation – the first generation was Bob Moog and Donald Buchla, but here we are and the synths are back thanks largely to the dance producer folks.”

From a designer’s point of view, how does the process of creating analogue instruments differ now compared to the ’70s? “Generally designing is easier since the design tools are so much better now,” Smith told us. “Some old components have been brought back, like the Curtis parts made by OnChip, Doug’s company, used in the Prophet-5. Other parts are hard or impossible to find, so we find alternate parts with the same analogue flavour.”

Tom Carpenter also sees positives in comparison to when he formed Analogue Solutions in the mid-’90s. “It’s easier in one sense – I now have 25+ years experience, and remember this doesn’t just cover synth design but also running a business and manufacturing. It takes knowledge of sheet metal, printing, packaging. Also shipping, tax laws and all aspects of running a business. But that 25 years+ means that each product evolves as I do, adding more adventurous features.”

For many reasons though, both designers flag how tough the current climate is. “It is getting harder,” Carpenter tells us. “The main reason is skyrocketing costs due to inflation and the global supply issues.” “In the last year, all ICs are hard to find and costs are going way up,” Smith explains.

Fake it 'til you make it

How does the threat look from the digital front? Are emulations close to eclipsing the need for authentic circuitry? Even ardent believer Tom Carpenter admits they’ve come a long way. “Many sound ‘the same’ in a blind test. Does it matter what instrument is used as long as the song is good? Perhaps not.”

The lure of analogue is not dead though. “Personally, I get no joy from using a fake,” he tells us. “A ‘clone’ of a synth is not the original.”

Dave Smith was more dismissive. “I haven’t tried any in many years,” he told us. “I’m guessing they have improved, though for me it’s about look and feel. I’d much rather be in front of a hardware synth with a set of knobs that never change or move. It’s all about interacting with a real musical instrument.”

What makes analogue effects so special?

It’s not only within the synth realm that analogue circuitry is prized. What does vintage effect technology have to offer over high-spec plugins?

Discussing ‘analogue’ in the effects realm is a little different to talking about synths. We often talk about analogue gear having ‘character’, which is generally always a good thing in a synth, but not necessarily so in an effect. Sure, many creative effects impart a certain sound to our music, but some mixing and mastering tools are best when transparent – doing their job without us really knowing they’re there.

The physicality is less of a dealbreaker too, as although some effects are great to manipulate by hand – live tweaking a filter, for example – in many cases the state-saving and automation available in software is far more desirable. That said, some effect types still work best in the analogue realm. Let’s take a look at a few notable examples.

Software compressors vs hardware compressors... 10 of the best

Analogue compressors come in various forms, but they tend to be prized for the characterful way they respond to signals, particularly when ‘pushed’ hard. A lot of this comes down to saturation – applying subtle harmonics for a ‘hi-fi’ sheen. This can have the effect of ‘glueing’ sounds together. For a cheap modern option, try UA’s new FET-equipped Volt interfaces.

Tape recorders/delays are still sought after for their distinctive but often desirable unreliability. This results in ‘wow’ and ‘flutter’ – subtle modulations in the speed and pitch of the audio. Tapes also impart a distinctive distortion, and tend to lose high content to create a ‘darker’ sound. To snag the analogue tone without breaking the bank, pick up a cheap tape recorder and bounce down your audio for authentic tape effects.

Channel strips in classic mixing consoles combined amplification, EQ and compression, each of which could impart a distinct character. These can be great for glueing bus channels together by adding subtle ‘warm’ saturation and a unified character across multiple elements. SSL’s SiX mixer offers authentic analogue channel strips at an affordable(ish) price.