While vapes or e-cigarettes first appeared around 20 years ago as an alternative to smoking, their prevalence and use have increasingly become problematic.

Governments and regulators are now catching up to what is widely seen as an addictive and unsafe product. Australia has just passed a world-first bill that will ban all vapes from general retail later this year.

Currently, the most predominant vapes on the market are single-use, disposable products designed to appeal to younger people. Despite their short lifespan, vapes are complex products that contain several valuable resources.

However, there are no practical means to collect or recycle vapes. Most end up as electronic waste or e-waste in landfill. Some are simply thrown on the street as litter. So what’s really inside vapes?

How do vapes work?

Vapes can be categorised as either reusable or disposable (single use), the more prevalent option.

Reusable vapes have a rechargeable battery and cartridge or liquid refills offered in a bewildering selection of flavours. More elaborate vapes contain microprocessors that offer customisable features, coloured LEDs and even small coloured screens.

In their simplest configuration, single-use disposables have the common components found in all e-cigarette types. Vapes contain a battery, a pressure sensor (like a modified microphone), an LED light, a heating element and a reservoir with e-liquid (the “juice”).

When the sensor is activated by taking a drag on the device, the battery provides power to a heating element that vaporises or atomises the liquid.

Tearing down a single-use vape

Analogous to the study of anatomy, teardowns are a technique used by industrial designers and design engineers to systematically disassemble a product.

This allows us to identify and describe the internal components and their relationships within a product. It can provide useful information about materials, manufacturing processes, assembly and technology.

Equally, it can provide insights into repairability, upgradability and ease of disassembly for end-of-life recovery for potentially valuable or harmful materials.

We obtained a random selection of commonly found, depleted, single-use vapes to teardown, identify and describe what is inside.

Housing

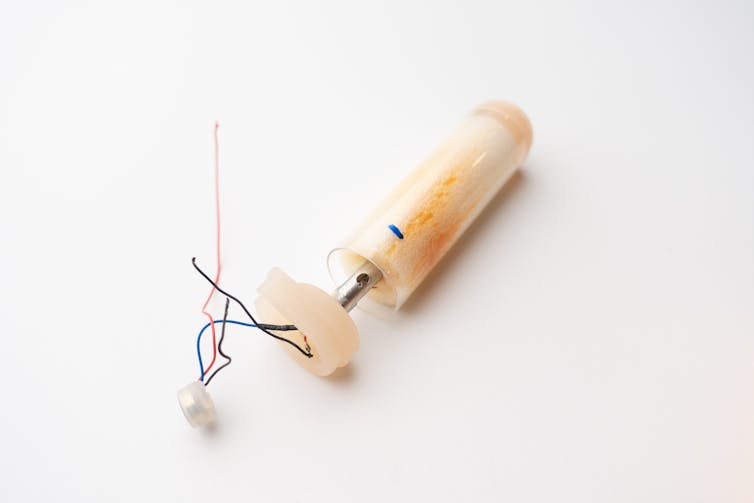

Disposable vapes are not designed to be disassembled. The main housing is made out of aluminium and covered in a paint finish and graphics, closed at the ends with plastic parts.

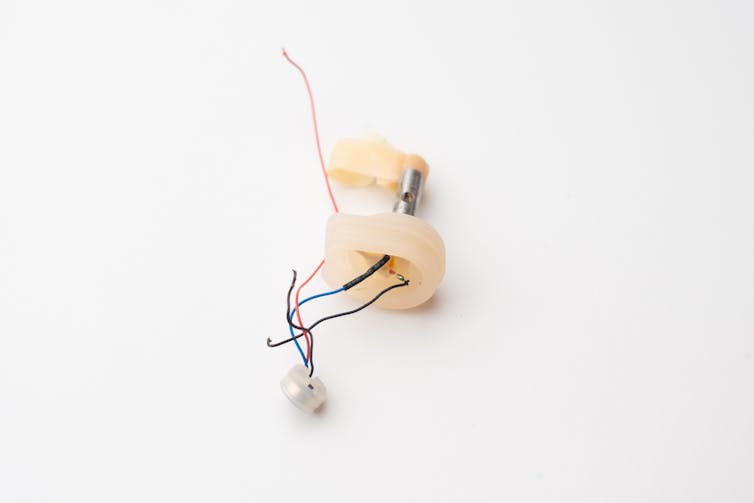

Once the housing end caps are removed, which is often not a straightforward task, the internal assembly slides out.

These internal parts are wedged or taped together within the main housing, and battery terminals are soldered to wires connecting to a pressure sensor and a heating element embedded in an e-liquid reservoir.

Battery

Despite disposable vapes being non-rechargeable, the ones we disassembled all contained a lithium battery. Although much smaller, they are not dissimilar to the bundles of batteries found in products like power drills and electric vehicles.

These cells have high-power density: they can store lots of electrical energy in a relatively small package. This is needed to supply periodic bursts of energy to the heating element, and to outlast the supply of e-liquid in the reservoir.

All the batteries we tested during the teardown of depleted single-use vapes still maintained a charge that could power a test light bulb for at least an hour.

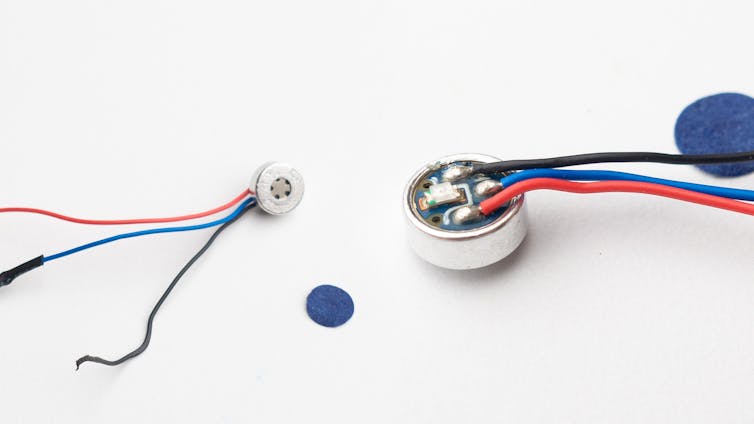

Pressure sensor

An air pressure sensor is a semiconductor switching device. Not unlike a microphone that converts vibrations into electrical energy, the pressure sensor detects a drop in pressure and closes an electronic switch.

This occurs during the action of taking a drag on the vape, which creates a partial vacuum within the device. When the switch is closed, a simple (short) circuit illuminates an LED and supplies current to the heating element.

Heating element: vaporiser

The heating element is embedded in a cap at one end of the e-liquid reservoir and connected to a wick. When the device is activated, an electrical current heats a metal strip that vaporises some of the volatile e-liquid.

The e-liquid reservoir

Disposable vapes contain an absorbent foam material saturated with e-liquid and contained in a plastic tube with silicone endcaps.

In the centre of the reservoir is a wicking material that draws in the surrounding e-liquid to be in contact with the heating element.

The e-liquid itself contains a range of ingredients such as propylene glycol, nicotine and flavourings, many of them with unknown health impacts.

Designed for the dump

The consumption of vapes has been skyrocketing in recent years, and they now represent a significant proportion of an alarming new category of e-waste.

Single-use e-waste results in a significant loss of valuable materials – notably aluminium and lithium.

Worse, when a disposable vape is thrown in the bin, the energy-dense lithium batteries pose a fire danger for waste management workers.

The materials in vapes also have toxic effects on the environment when released.

Having potentially valuable metals mixed with other, low-value materials such as plastic makes vapes difficult to separate and recycle. Overall, single-use vapes are clearly wasteful of resources and dangerous in the environment.

Miles Park does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.