What distinguishes a company that makes "good" chocolate (chocolate untainted by child labor, modern slavery, deforestation and the overuse of agrichemicals) from one that merely makes chocolate?

Our annual Chocolate Scorecard investigation, which is a collaboration between Be Slavery Free, Macquarie University, The University of Wollongong and the Open University, suggests it might be a mission that goes beyond making food and profit.

'Good eggs' trumpet ambition

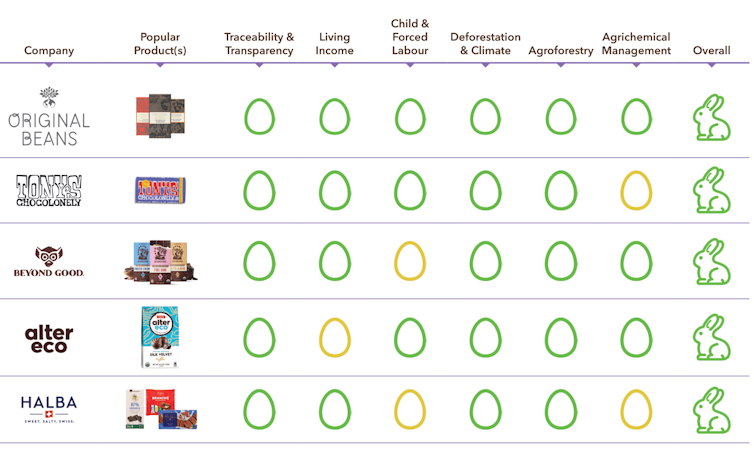

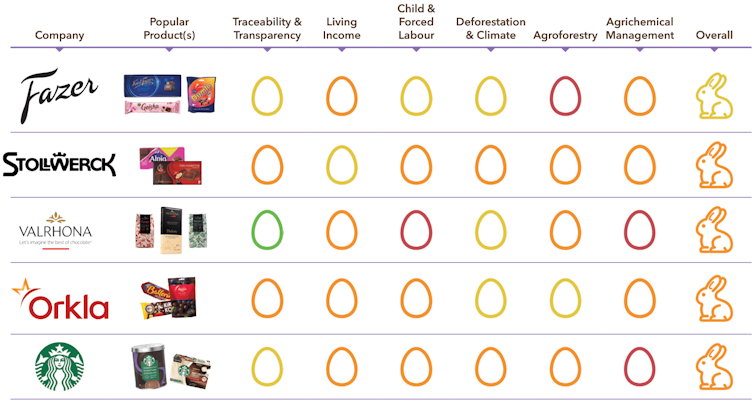

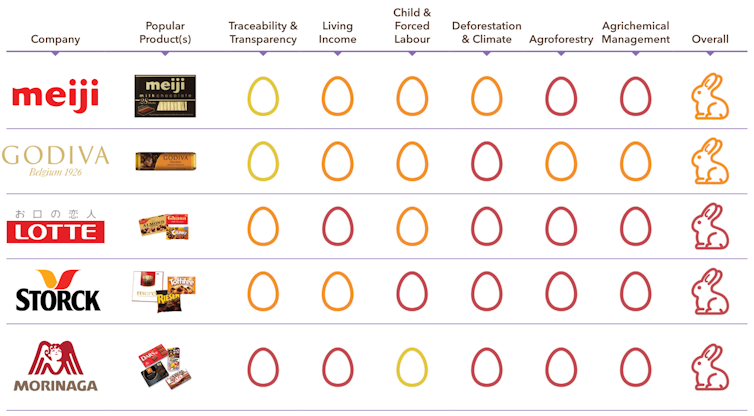

Only five of the 38 leading global chocolate makers we assessed received our green "good egg" award for exemplary practices.

They are the Netherlands-based Orignal Beans and Tony's Chocolonely, Madagascar's Beyond Good, US-based Alter Eco and Switzerland's HALBA.

Original Beans are at the forefront of Europe's artisan chocolate revolution. Its mission statement includes the words "regenerate what you consume". Its website asks its customers to "heal the future, don't steal it".

Tony's Chocolonely has as its mission making slave-free chocolate and turning all chocolate slave-free.

It says 60% of the world's cocoa comes from 2.5 million farms in West Africa that are placed under the kind of pricing pressure that leads to child labor and modern slavery. The average cocoa farmer earns less than US$1.20 per day and women cocoa farmers are thought to earn around 50 cents per day.

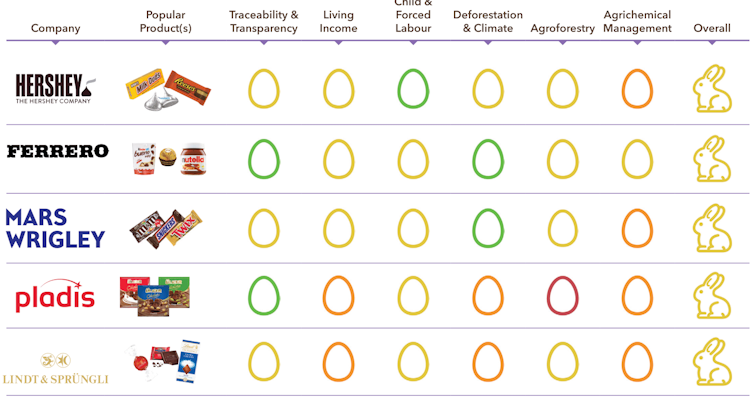

'Broken eggs' say little

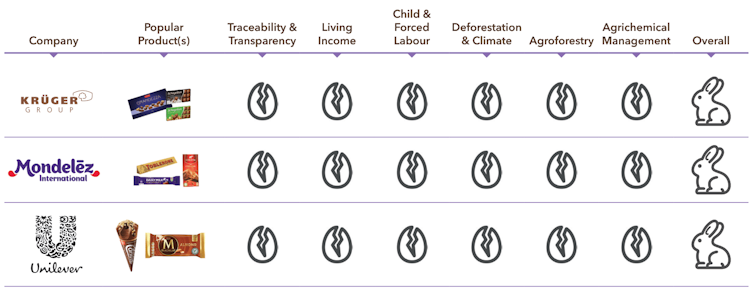

At the other end of the scale, firms such as Unilever (which makes Magnum ice creams) and Mondēlez (which makes Cadbury) were awarded "broken eggs" for not engaging with the survey.

Mondēlez describes its mission as going "the extra mile to lead the future of snacking around the world", rather than tackling environmental or social concerns.

It's a long way from Cadbury's original mission. Founder John Cadbury was a Quaker "driven by a passion for social reform" who helped found the forerunner to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and planned a "model village" for his workers including schools, shops, parks and childcare.

In 2022, Britain's Channel 4 broadcast undercover footage from Ghana purporting to show children as young as 10 barefoot, wearing shorts and T-shirts, using machetes to harvest cocoa pods and sharpened sticks to extract beans that were eventually used in Cadbury chocolate.

Mondelēz said it was deeply concerned. It explicitly prohibited child labor and had been making significant efforts to improve the protection of children in the communities where it sourced cocoa, including Ghana.

If such efforts are afoot, Chocolate Scorecard would like to hear about them.

'Rotten eggs' can improve

Among those companies that did respond, there are signs of improvement. In 2020, Godiva received a "rotten egg" award for "failing to take responsibility for the conditions with which its chocolates are made despite making huge profits off its chocolate".

Godvia now says it is dedicated to "a sustainable and thriving cocoa industry where farmers prosper, communities are empowered, human rights are respected, and the environment is conserved".

It has earned an "orange" rating, demonstrating that progress is achievable.

Similarly, Sücden — a previous red "rotten egg" — improved to yellow in this year's scorecard.

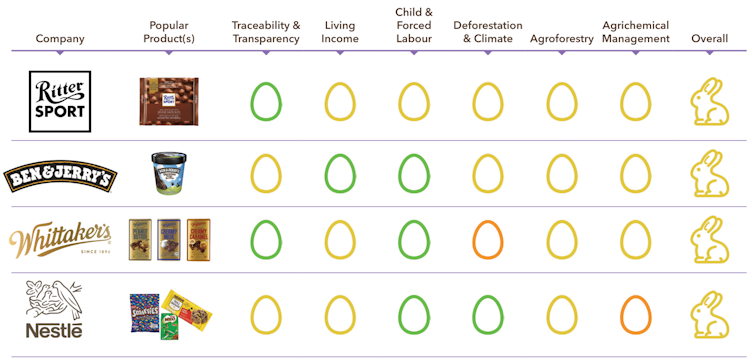

Nestlé's inclusion in this years top ten gives us hope.

It now says its purpose is to "unlock the power of food to enhance quality of life for everyone, today and for generations to come".

Companies require profits to survive. But if profit and making chocolate are their only drivers, they are likely to hurt people and the environment while doing it.

This Easter it is possible to support firms that are making profits without hurting the planet or its inhabitants. Our scorecard finds there are more and more of them.

John Dumay, Professor - Department of Accounting and Corporate Governance, Macquarie University; Cristiana Bernardi, Senior Lecturer in Accounting and Financial Management, The Open University; Samuel Mawutor, PhD Student in Geography and Geospatial Sciences, Oregon State University, and Stephanie Perkiss, Associate professor, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.