NEW YORK — Nearly 200 years after Ludwig van Beethoven’s death, researchers pulled DNA from strands of his hair, searching for clues about the health problems and hearing loss that plagued him.

They weren’t able to crack the case of the German composer’s deafness or severe stomach ailments. But they did find a genetic risk for liver disease, plus a liver-damaging hepatitis B infection in the last months of his life.

These factors, along with his chronic drinking, were probably enough to cause the liver failure that is widely believed to have killed him, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Current Biology.

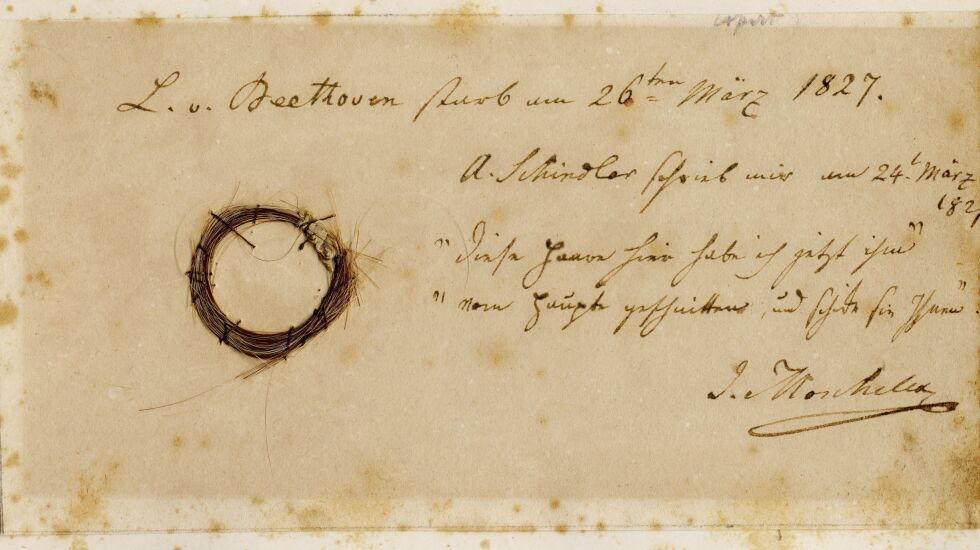

This Sunday marks the 196th anniversary of Beethoven’s death in Vienna on March 26, 1827, at the age of 56. The composer himself wrote that he wanted doctors to study his health problems after he died.

“With Beethoven in particular, it is the case that illnesses sometimes very much limited his creative work,” said study author Axel Schmidt, a geneticist at University Hospital Bonn in Germany. “And for physicians, it has always been a mystery what was really behind it.”

Since his death, scientists have long tried to piece together Beethoven’s medical history and have offered a variety of possible explanations for his many maladies.

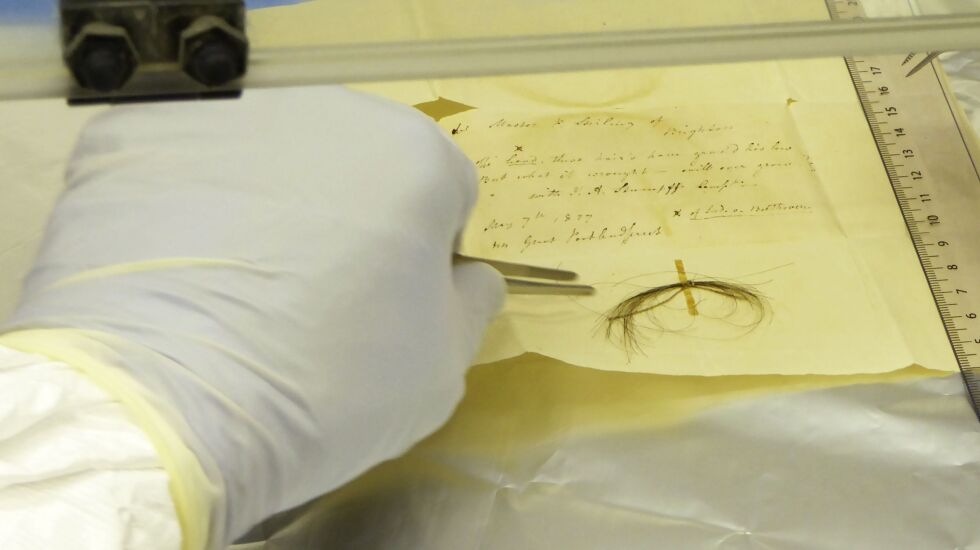

Now, with advances in ancient DNA technology, researchers have been able to pull genetic clues from locks of Beethoven’s hair that had been snipped off and preserved as keepsakes. They focused on five locks that are “almost certainly authentic,” coming from the same European male, according to the study.

They also looked at three other historical locks, but weren’t able to confirm those were actually Beethoven’s. Previous tests on one of those locks suggested Beethoven had lead poisoning, but researchers concluded that sample was actually from a woman.

After cleaning Beethoven’s hair one strand at a time, scientists dissolved the pieces into a solution and fished out chunks of DNA, said study author Tristan James Alexander Begg, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge.

Getting genes out was a challenge, since DNA in hair gets chopped up into tiny fragments, explained author Johannes Krause, a paleogeneticist at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

But eventually, after using up almost 10 feet (3 meters) of Beethoven’s hair, they were able to piece together a genome that they could “quiz” for signs of genetic disease, Krause said.

While researchers didn’t find any clear genetic signs of what caused Beethoven’s gastrointestinal issues, they found that celiac disease and lactose intolerance were unlikely causes. In the future, the genome may offer more clues as we learn more about how genes influence health, Begg said.

The research also led to a surprising discovery: When they tested DNA from living members of the extended Beethoven family, scientists found a discrepancy in the Y chromosomes that get passed down on the father’s side. The Y chromosomes from the five men matched each other — but they didn’t match the composer’s.

This suggests there was an “extra-pair paternity event” somewhere in the generations before Beethoven was born, Begg said. In other words, a child born from an extramarital relationship in the composer’s family tree.

The key question of what caused Beethoven’s hearing loss is still unanswered, said Ohio State University’s Dr. Avraham Z. Cooper, who was not involved in the study. And it may be a difficult one to figure out, because genetics can only show us half of the “nature and nurture” equation that makes up our health.

But he added that the mystery is part of what makes Beethoven so captivating: “I think the fact that we can’t know is OK,” Cooper said.

AP journalist Daniel Niemann contributed to this report from Bonn, Germany.