Ballun from Getty Images Signature; Canva

What Is Quantitative Tightening?

The main job of a central bank, like the Federal Reserve, is to keep the economy strong through maximum employment and stable prices. It does this by managing the Fed Funds Rate, which it sets at its Federal Open Market Committee meetings. This effectively raises or lowers the interest rates that banks offer companies and consumers for things like mortgages, student loans, and credit cards.

But when the economy needs help and interest rates are already low, the Fed must turn to other tools in its arsenal. This includes practices like quantitative easing and quantitative tightening; the former expands the shares of Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and even stocks on the government’s balance sheets, while the latter tightens the monetary supply. Both have a profound effect on liquidity in the financial markets.

The Fed came to the rescue with trillions of dollars’ worth of quantitative easing at the end of the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis, and again during the global Coronavirus pandemic.

But the Fed can’t go on printing money forever. Whenever it employs quantitative easing, the Fed must eventually turn to its counterpart, which is known as quantitative tightening, in order to limit some of the negative outcomes of the former, such as inflation.

How Does Quantitative Tightening Work? What Is an Example of Quantitative Tightening?

Through quantitative tightening, the Federal Reserve reduces its supply of monetary reserves in order to tighten its balance sheet—and it does so simply by letting the bonds and other securities it has purchased reach maturity. When this happens, the Treasury department removes them from its cash balances, and thus the money it has “created” effectively disappears.

Does the Fed know exactly when to ease the gas pedal on quantitative easing? According to the Fed, timing is everything. Remember how the Fed’s main job is to create a strong economy through stable prices and high employment? As it carefully monitors the effects interest rates are having on the economy, it also keeps a close eye on the overall measure of inflation. It’s both a constant battle and a juggle.

Take the period following the Financial Crisis as an example. The 2007–2008 crisis stemmed in large part from the implosion of collateralized debt obligations, and so the Fed kept the Fed Funds Rate at virtually 0% for almost a decade in order to spur growth and maintain stable rates of employment.

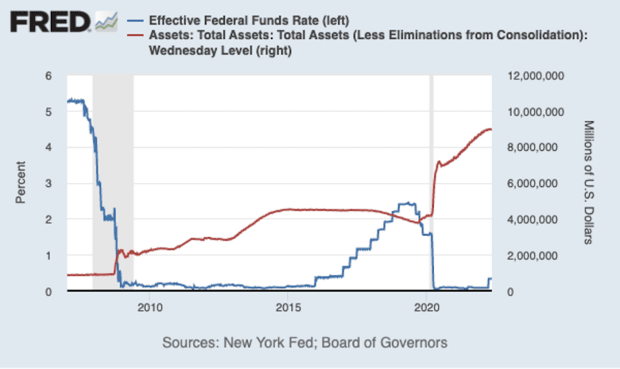

During this period, it also undertook a series of quantitative easing measures, watching its balance sheet balloon from $870 billion in August 2007 to $4.5 trillion in September 2017.

The FRED graph below illustrates how the Fed Funds rate, in blue, remained at nearly zero for the period while the total size of the Fed’s balance sheet, in red, grew. The shaded areas indicate recession.

The Fed believed that as soon as employment became stable, it needed to turn its attention to meeting its 2% inflation target, which it accomplished by raising interest rates. And so, in October 2015, it began gradually increasing the Fed Funds Rate in 25 basis point increments. Over the next several years, rates went up from 0.0%–0.25% levels to 2.25%–2.5% in 2018. This course of action, in the Fed’s words, was known as liftoff.

After raising rates a few times with no disastrous consequences, in 2017 the Fed next embarked on an effort to reduce its balance sheet through quantitative tightening. This was also known as unwinding its balance sheet because it was taking action in a slow and gradual way.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Fed let about $6 billion of Treasury securities mature and $4 billion of mortgage-backed securities “run off” per month, increasing that amount every quarter until it hit a maximum of $30 billion in Treasuries and $20 billion in mortgage-backed securities per month. By July 2019, the Fed announced that its unwinding was complete.

The Fed published a blog post detailing these efforts, categorizing them as its “balance sheet normalization program,” since it sought to “return the policy rate to more neutral levels.”

What Effect Does Quantitative Tightening Have on the Economy?

While the goal of quantitative easing is to spur growth, quantitative tightening doesn’t hinder it; in fact, many Governors of the Federal Reserve believe quantitative tightening doesn’t have much effect on the economy at all.

“Quantitative tightening does not have equal and opposite effects from quantitative easing,” said St. Louis Fed President Jim Bullard, “Indeed, one may view the effects of unwinding the balance sheet as relatively minor.”

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen famously described quantitative tightening as “something that will just run quietly in the background over a number of years,” and that “it’ll be like watching paint dry.”

St. Louis Fed Research Director Chris Waller compared quantitative tightening with “slowly opening the stopper in a drain and letting the water run out,” and by doing so, they were “letting the supply of U.S. Treasuries in the hands of the private sector grow.”

But critics have argued that the excess reserves the Fed creates by “printing money” through quantitative easing have negative consequences on the overall economy. For example, these reserves can lead to currency devaluation and higher inflation, which is defined as when prices rise faster than wages. Inflation can have disastrous effects on an economy, resulting in asset bubbles and even recessions.

Even the Fed admitted as much when St. Louis Vice President Chris Neely noted that between 2008–13, the Fed’s asset purchases led to a decrease in 10-Year Treasury yields by 100–200 basis points. He said, “this reduction modestly raised prices and real activity.”

Just remember that the Fed’s principal aims are to generate stable prices and high employment. So while the Fed hasn’t explicitly said so, reducing its balance sheet might be one of its methods to combat inflation.

Why Is Quantitative Tightening on the Fed’s Agenda Again?

In 2022, inflation reached decades’ high, stemming from a number of factors, including fallout from the global Coronavirus pandemic, which increased labor prices, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which affected energy and commodities. In March, 2020, the Fed slashed the Fed Funds rate to 0.00%–0.25% in response to the pandemic. In May, 2022 it increased by 0.5%, beginning a series of rate hikes that continued through the summer and fall.

What Is the Schedule for Quantitative Tightening?

In the spring of 2022, the Fed announced it would be undertaking a “phased approach” of quantitative tightening measures beginning with a 3-month period of unwinding $30 billion of Treasuries and $17.5 billion in mortgage-backed securities. By September 2022, these caps increased to $60 billion and $35 billion, respectively.

Is Quantitative Tightening Really So Frightening?

TheStreet’s Ellen Chang says that, according to economists, inflation is on a downward trend, most likely to decline to 3% by the end of the year, and that higher interest rates as well as quantitative tightening should do what they’re supposed to, and reduce pricing pressure.