This month has seen the release of the second series of Good Omens, the comedic tale of an unlikely friendship between a Biblical angel and a demon who join forces to save the world. It’s based on the book of the same name written by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, and is a huge hit with critics (and presumably audiences, although Amazon Prime do not publish viewing figures).

Following Netflix’s Sandman, the show marks the second successful screen adaptation of Gaiman in the last 12 months, yet the same cannot be said of Pratchett, despite him being the better selling author.

Why the lack of screen success? What is it about the books of Terry Pratchett that make them so difficult to adapt?

Terry Pratchett and the Discworld novels

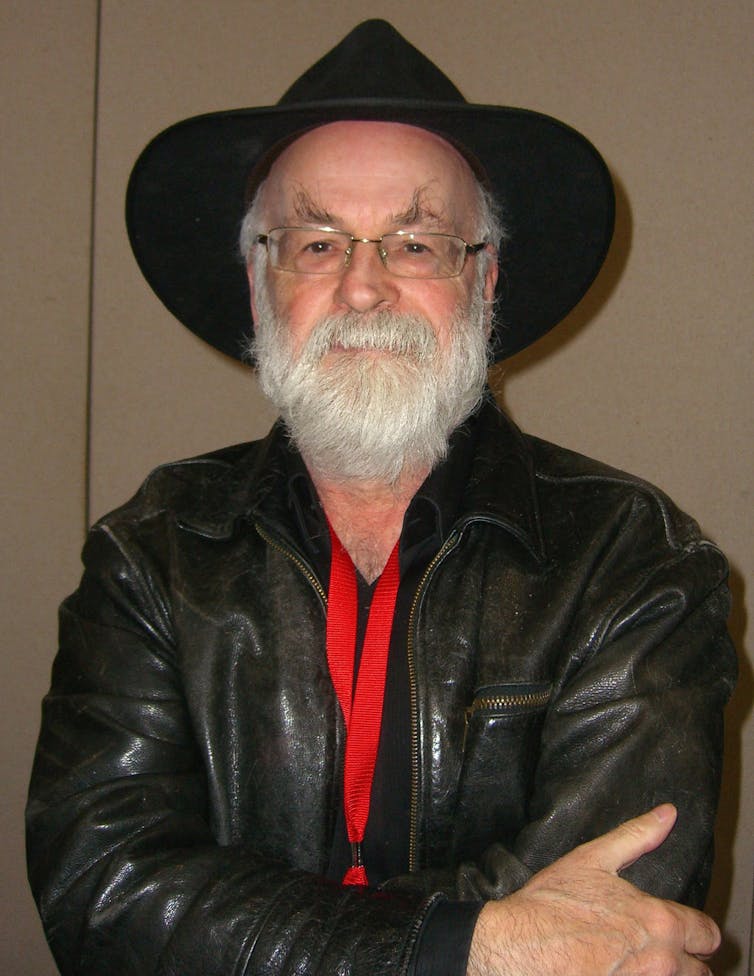

When you delve into the world of literature, few names shine as brightly as Terry Pratchett’s. Despite his early death, the prolific British author continues to enchant readers with his Discworld book series, a fantasy universe that satirises our own with clever wit and insightful humour.

His social commentary is so astute, in fact, that his fictional measure that truly measured the nuances of financial inequality has recently been taken up by a real anti-poverty campaign in the United Kingdom.

In short, he is one of the greatest novelists of all time.

Yet despite Pratchett having written more than 40 novels, the odds are that most people reading this will either not have read him, nor even heard of him. One reason could be that he worked almost exclusively in the realm of fantasy. Most likely it’s because there is yet to be a genuinely successful or definitive screen adaptation of his solo work that would bring him to a more mainstream audience.

Screen Adaptations

Including Good Omens, there have been 11 small screen adaptations of Pratchett’s work in 32 years, both animated and live action (from very low to quite medium budget), although intriguingly none yet for the silver screen.

Seven have been set in his legendary Discworld. Some have been incredibly faithful adaptations - Hogfather (2006) pretty much replicates every scene in the book in order. Others have taken varying levels of artistic licence, the most controversial being The Watch (2022) which completely reimagined character, setting and tone.

What they all have in common is that none have cut through into the public consciousness. We’re still waiting for that Terry Pratchett adaptation. Where is his BBC version of Pride & Prejudice? His Fight Club? His Lord of the Rings?

A clash of cultures

It appears to be the age-old issue that plagues all screen adaptations of the written word: narration.

Pratchett’s writing style is whimsical, all sharp satire wrapped in well-observed humour. But most of this is contained not in the dialogue or dramatic situation, but the narration. The choice of word, the turn of phrase, or even CAPITALISATION (the main character of Death only SPEAKS IN CAPTIALS) all contribute to the uniqueness of Pratchett’s voice and joy of the stories.

Contrast this with how screen practitioners, mostly notably screenwriters and directors, are taught to consider their craft. As influential script guru Robert McKee famously stated, voiceover is an “indolent practice”, the last hope of a truly desperate filmmaker. As cinema evolved from photography it is often (erroneously) thought of as a completely visual medium, whereby the perfect film would be one that required no dialogue at all.

Read more: Terry Pratchett, Jane Austen, and the definition of literature

A visual medium

The issue is that film and television are not purely visual mediums. Just ask John Williams. Moving pictures may be the dominant technique, but the art form relies on so many others. Film was famously referred to as the seventh art, and is the only one able to encompass the other six (architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry and dance).

Voiceover is a very easy technique to get both right or wrong. You repeat what we see on screen (bad), you add to it or counterpoint it (good). It is unfortunate the most famous voice-overs are the ones maligned for being awful, the go-to proof of their inadequacy being the original cut of Blade Runner (1982). However, the film is ironically heralded today as the definitive Philip K. Dick adaptation, even though the author disliked that the film completely reversed the central thematic idea his novel.

Yet for every Blade Runner, there is a Trainspotting (1996). The opening voiceover is an oft-repeated classic, as are those from Apocalypse Now (1979) and Sunset Boulevard (1950).

But when we come to any screen adaptation of Pratchett, there is almost no narration, either in voice or text form. No searingly funny footnotes giving satirical background or new perspective.

This is a problem, as it is this narration that is the soul of his books, and when removed wholesale all that is left is a series of events that have been robbed of their context. The adventures may be fun, the characters eccentrically diverting, but little more.

Interestingly, this was an accusation aimed at The Watch (2022), the most recent adaptation that deviated so far from the original work that it not only removed narration, it essentially removed Pratchett. His daughter Rihanna did not criticise the show but did note that it “shares no DNA with my father’s Watch”. A more direct critic was Neil Gaiman, pointing out that “it’s not Batman if he’s now a news reporter in a yellow trenchcoat with a pet bat”.

This returns us to Good Omens. It uses neither voiceover nor text, yet is a successful adaptation and represents a huge leap forward for Pratchett on screen. However, it is based on a source novel that is as equally Gaiman’s as Pratchett’s, with the screen version even more so as Gaiman served as showrunner.

This means we’re still waiting for the definitive Pratchett on the big or small screen. But there is hope in sight. Rihanna Pratchett is currently working with screen partners to create “truly authentic […] prestige adaptations that remain absolutely faithful to (his) original, unique genius”.

Does this mean that there will be narration and footnotes? Let’s hope so.

Darren Paul Fisher does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.