An ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus. This happens in roughly 2% of pregnancies.

As a nurse-midwife and reproductive health researcher, I think it is critical to understand this relatively common pregnancy complication.

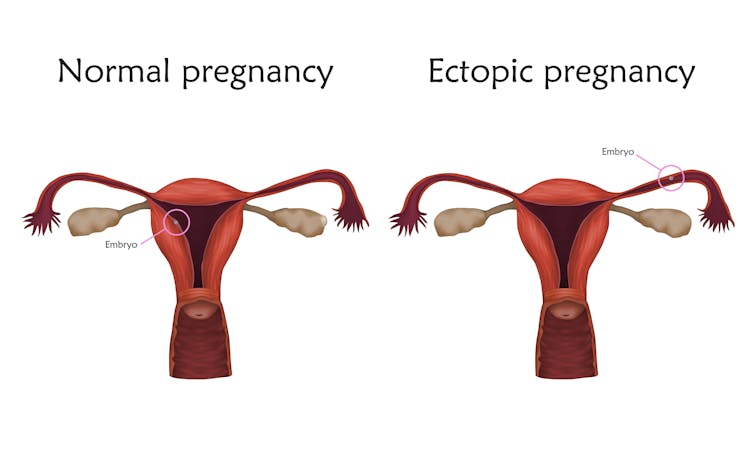

Normally, egg and sperm meet and combine inside a uterine tube. The fertilized egg travels through the tube and into the uterus, implants in the uterine lining and grows. But sometimes the fertilized egg doesn’t make it all the way to the uterus, implanting in the tube instead. The egg can also end up in an ovary, the cervix or the abdomen. Fertilized eggs have even implanted in scars from previous Caesarean births or other surgeries. But more than 90% of ectopic pregnancies are tubal.

Carrying tubal pregnancies to term is nearly impossible because a fertilized egg won’t survive long attached to locations outside the uterus. Other structures in the body simply can’t protect or nourish an embryo.

People at greatest risk for ectopic pregnancy have had one before. The risk is also higher in those with previous pelvic infections or past uterine surgeries. In vitro fertilization also increases the risk. Half of ectopic pregnancies, however, occur in people with no risk factors at all

Why ectopic pregnancy matters

Ectopic pregnancy is dangerous. The implanted embryo just keeps growing in the narrow uterine tube. By about the third week after implanting, the embryo is large enough to put pressure on the tube from inside.

As the pressure builds, the patient typically has symptoms like one-sided lower abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding and fainting. When pressure from the growing embryo ruptures the tube, the patient feels stabbing or tearing pain on one side of the abdomen near the groin, along with a blood pressure drop and other symptoms of shock. Rupture causes hemorrhaging that can be deadly if untreated by surgery. Ectopic pregnancies are the leading cause of first-trimester maternal mortality.

Treatment depends on the patient’s health history and a medical assessment of their condition. Healthy individuals at low risk of imminent rupture may receive a gluteal injection of methotrexate. A drug that also treats cancers and autoimmune disorders, methotrexate makes it harder for cells to form DNA or to multiply. The embryo stops growing, and the body eventually reabsorbs it. One or two doses is usually effective.

If the uterine tube has ruptured, the patient needs emergency surgery. Through a small incision, the surgeon removes the embryo from the uterine tube, sometimes with all or part of the tube itself.

Treating this condition ends the pregnancy, which is why some people conflate ectopic pregnancy treatment with elective abortions. But with or without intervention, ectopic pregnancies won’t survive past the first few months. Instead, they end long before a healthy birth is possible.

It’s also impossible to “save” an ectopic pregnancy by moving the embryo to the uterus. Removing the embryo from the implantation site causes irreparable damage to the embryo. That’s why, despite the claims behind recent failed legislation, doctors cannot move an ectopic pregnancy from its original location to the uterus.

Amy Alspaugh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.