Last week we described Clever Hans, a remarkable horse whose handler fooled people into thinking that his steed was capable of feats such as adding and subtracting numbers. There seemed no limit to what he could do.

Overlooked in these stories is that these abilities would require Hans to interpret human language. That in itself is a major skill, and even now, AI systems can only do it in a crude way.

When Hans was tested with the help of his owner, Herr von Osten, the notion that a horse could be that clever was thoroughly disproven. And yet von Osten stuck by his original claims.

Was this a case of cognitive dissonance? Hans could do maths. But Hans could not do maths.

When psychologist Leon Festinger coined the term in 1957, he cited examples such as doomsday cult members who, when the end of the world did not happen when they said it would, simply moved it to another date.

They imagined all sorts of reasons to explain away the discrepancy.

Studies* have shown that everybody bar Ask Fuzzy readers are prone to some level of cognitive dissonance, ranging from trivial to severe. In lab experiments, a person asked to explain an unconscious action, quickly found a way to post-facto rationalise what they'd done.

More serious versions include denial that smoking is harmful, that you can drive safely after another drink, or that fossil fuels are good for the planet.

While it's risky to infer cognitive dissonance on a someone who died a hundred years ago, we can see a very rational explanation. After the experiments, von Osten continued to tour and do shows with his horse Clever Hans.

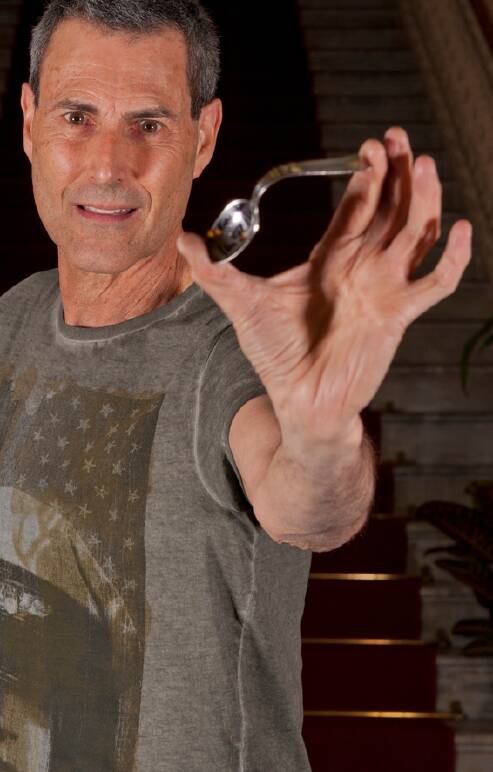

In that, he was a bit like Uri Geller who amused people for many years with his performances bending spoons. He claimed that extraterrestrial beings gave him amazing paranormal powers. He threatened legal action against people who challenged him.

This story tells us something about the inherent conflict between science and human nature.

There are powerful emotional reasons why we cling to a belief that is demonstrably untrue.

Science, however, is a methodical attempt to undermine human irrationality and vested interests.

In its purest form, it's a ruthless slayer of failed ideas. Research is supposed to be tested against the "null hypothesis" that is designed to prove you wrong.

Of course, in practice, science is done by humans who are complex bundles of emotions and motivations, which means it can - and does - sometimes go wrong.

Still, it's an endeavour that's crucial to our future, even when it leads to comfortable conclusions that we'd rather not hear.

- * This unpublished research has been published.

Listen to the Fuzzy Logic Science Show at 11am Sundays on 2XX 98.3FM.

Send your questions to AskFuzzy@Zoho.com Twitter@FuzzyLogicSci