When a bipartisan majority of 53 senators vote to confirm Ketanji Brown Jackson to the US Supreme Court on Thursday, yet another attempt to derail a nomination to the high court by a Senate minority will come up short.

Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee used the words “child porn” more than 160 times over the course of the four-day confirmation hearing as they falsely claimed Ms Jackson’s sentencing record towards those convicted of possessing child sex abuse images was more lenient than most other judges.

This clear attempt to render the Harvard-educated jurist politically unpalatable using the spectre of shocking or outrageous conduct is nothing new, nor has it been particularly successful.

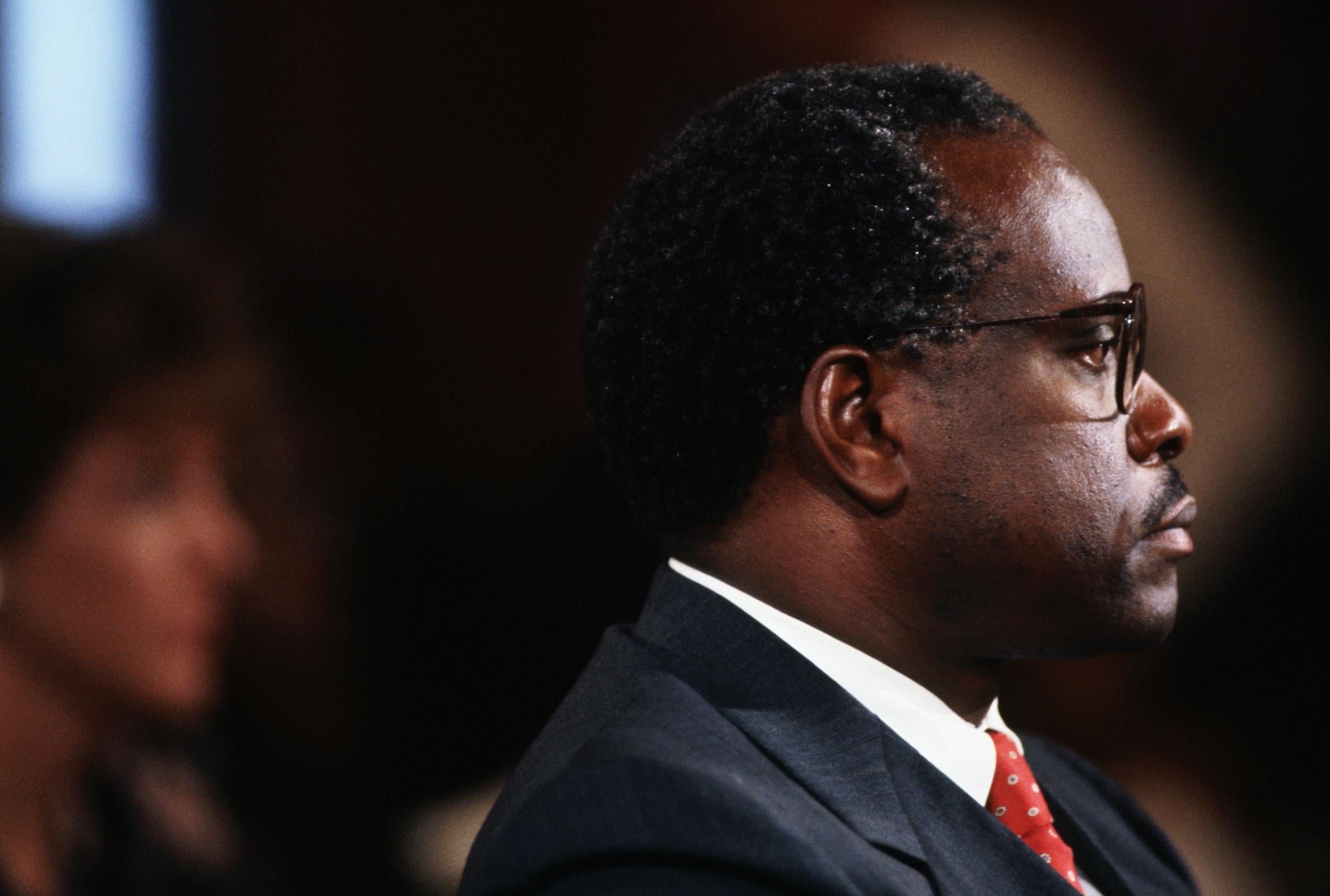

That hasn’t stopped both parties from deploying the strategy, which was first given a name in 1991, when George HW Bush was president of the United States, Paula Abdul’s Rush, Rush was topping the Billboard charts, and District of Columbia Circuit Judge Clarence Thomas was getting ready to appear for his Supreme Court confirmation hearing before the US Senate.

And Flo Kennedy, a women’s rights activist and attorney, was not happy about the Republican president’s choice of an avowed opponent of affirmative action programmes and self-described “originalist” judge to replace the legendary civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall on the nation’s highest court.

“We’re going to Bork him,” she said in an interview with the Associated Press.

Ms Kennedy’s declaration was a neologism coined from the name of the last Supreme Court nominee to be voted down by the Senate, District of Columbia Circuit Judge Robert Bork.

Bork, a strong proponent of “originalism” — the view that the US Constitution should be interpreted based on the meaning of the provisions at the time they were written — in the late 18th or 19th centuries — was already an infamous figure by the time his name was placed in nomination to replace the retiring Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell.

As solicitor general in 1973, he’d carried out then-president Richard Nixon’s order to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox after then-attorney general Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus resigned rather than comply.

In a memoir published after his death, Bork said Nixon had promised to name him to the Supreme Court if he agreed to do what Mr Richardson and Mr Ruckelshaus had not been willing to do.

Nixon never got the chance to make good on his promise, but when Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981, he began appointing avowed originalists to the federal bench, and Bork was rewarded with a seat on the DC Circuit — generally considered the nation’s highest court — in 1982.

His nomination was approved by the GOP-controlled Senate by voice vote, not a step usually taken for controversial nominees.

But when Judge Bork was nominated to become Justice Bork five years later, it was a whole different ballgame.

West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd, who’d become Senate majority leader when Democrats had taken control of the upper chamber in the 1986 midterm elections, had said a nomination of Bork “would be inviting problems” because of his role in Watergate.

The Senate Majority Whip, Alan Cranston of California, also urged his caucus to form a “solid phalanx” against any nominee thought to be an ideological extremist, a category most Democrats thought inclusive of Bork.

But it was Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy who served as the tip of the spear against Bork by delivering an incendiary speech from the Senate floor not one hour after his name had been placed in nomination.

“Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters,” said Kennedy. “Rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, and schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens.”

Two and a half months went by before the Senate took up Mr Bork’s nomination at a confirmation hearing, during which Mr Kennedy’s attacks were backed up by television ads narrated by none other than actor Gregory Peck, who’d played Atticus Finch in the film adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Bork, the advertisement said, “has a strange idea of what justice is”.

The man who’d played an attorney defending a Black man in the segregated south told TV viewers Bork had “defended poll taxes and literacy tests which kept many Americans from voting” and “opposed the civil rights law that ended ‘Whites only’ signs at lunch counters”.

Though the Senate Judiciary Committee voted 9-5 to recommend his nomination favourably to the full sSenate, it was clear at that point that the Democratic-controlled body would reject him.

Nonetheless, Bork refused to withdraw his name from contention, instead releasing a statement calling for “a full debate and a final Senate decision”.

On 23 October 1987, Bork got that decision.

Fifty-two Democrats and six Republicans voted to reject him, the largest margin against a Supreme Court nominee in over a century.

Despite Bork’s name becoming synonymous with acting to scuttle a judicial nominee by rendering them politically untenable for senators, subsequent attempts at convincing senators to reject nominees have invariably failed.

Yet over the years, the party out of power in the White House has done its level best to make it difficult for presidents to appoint justices to the court, particularly when they’ve been put up by a Republican president.

Twice, Democrats have tried to invoke allegations of sexual harassment or assault against nominees — Clarence Thomas in 1991 and Mr Kavanaugh in 2018 — and both times used emotional witness testimony in an attempt to swing key senators against their nominations.

Both times, the effort failed.

And despite Republicans’ attempt to replicate Democrats’ prior tactics, Judge Jackson will soon be sworn in as Justice Jackson.

Senator Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat and one of the longest-serving Senate Judiciary Committee members, told The Independent that “Borking” tactics don’t seem to work anymore because senators are “considering these things in a different way” and “there isn’t a taste” for it right now.

A Republican, Utah’s Mitt Romney, suggested the lack of effective “Borking” stems from the problems posed for a Senate minority when the majority and White House are aligned.

He said “circumstances might change” if the Senate majority were held by the “opposition party”.

“Were that the case, we’d probably have a different circumstance,” he said.