In the investing world, hedge funds and other large, institutional investors often use a strategy called short selling to make money. Short selling is a bearish strategy wherein an investor borrows shares of a stock they think will decline in price, then sells them immediately at their current market price.

Once the shares are due back to the lender, the investor buys them back in the open market (ideally at a significantly lower price), then returns them, pocketing the difference between their initial sale price of the borrowed shares and their subsequent repurchase price of the shares they then returned.

What Is a Short Squeeze in Simple Terms?

A short squeeze occurs when a stock that has been heavily shorted (bet against) by many hedge funds and other institutional investors rises in price unexpectedly, causing those who have shorted the stock to buy it back in large amounts in order to cover their short positions. In doing so, these institutional investors drive the price of the stock in question even higher, prompting others with short positions to panic and do the same.

This phenomenon can cause a sudden and meteoric rise in the price of the shorted stock. When this does occur, the hedge funds that bet against the stock lose quite a bit of money, but any investors lucky enough to have held a long position in the stock before the squeeze can make very substantial gains—if they sell the stock at or near its peak.

How Do Short Squeezes Work? Why Do they Occur?

When a hedge fund or other investor borrows shares of a stock with the intent of shorting it, they are required to return the same number of shares after a certain period of time (the term of the loan)—regardless of whether the stock in question has gone down in price (like they expected) or not.

This means that if their prediction turns out to be incorrect, and the market price of the stock they shorted rises significantly during their borrowing period, they still have to buy back the shares they borrowed (usually a large amount) and return them to the lender—even if this means taking a loss on the trade.

It’s important to remember here that the market price of any stock is a product of supply and demand. When a stock has more buyers than sellers, its price goes up, and vice versa.

So, if the price of a stock goes up enough that the hedge funds that bet against it start worrying about how much money they might lose if it keeps going up, they might buy back all of the shares they’ve borrowed and return them early for fear of additional losses. In doing so, they drive the price of the stock up even further, prompting others who have shorted the stock to do the same.

At the same time, other investors who haven’t shorted the stock may notice its upward momentum and buy in. Together, the massive buy orders from those with short positions combined with the wave of new buy orders from interested investors make the stock’s demand far outweigh its supply, pushing its price upward rapidly.

If this happens on a large enough scale, the underlying stock’s price can rise to previously unheard-of levels over a very short timeframe.

Who Stands to Profit From a Short Squeeze?

When a short squeeze does occur, those who held long positions in the stock in question before the squeeze began (and those who bought in during the early stages of the squeeze, to a lesser degree) certainly stand to pocket a pretty penny—if they’re paying attention. Assuming these investors are able to identify the peak of the squeeze and sell their shares at that time, three-figure percentage gains are not out of the question.

That being said, it can be difficult for the average investor to know when a short squeeze has reached its peak. One way an average investor could mitigate this difficulty is by watching the market and placing consecutively higher stop-loss sell orders as the stock in question continues to go up in price. This way, if and when the price does begin to fall, their order will be triggered, and their position will be liquidated as the stock’s price begins to decline.

How Long Does a Short Squeeze Usually Last?

In general, short squeezes tend to last somewhere between several days and several months. There is no real “typical” length for a short squeeze, as each one is unique.

That being said, every shorted stock has a different amount of short interest and a different short interest ratio, and these factors can be used to guess at the potential length of a squeeze.

What Is Short Interest?

A stock’s short interest is simply the number of shares that have been sold short and have yet to be returned to their lenders. The more short interest a stock has, the more the market is betting against it.

What Is a Short Interest Ratio (Days-to-Cover)?

A short interest ratio (sometimes referred to as days-to-cover) is a metric that can be useful in determining how many days it would likely take for all open short positions in a stock to be covered should the stock rise in price. It is calculated by dividing a stock’s short interest by its average daily trading volume.

The result is—theoretically—the number of days it would take for all open short positions to be covered in the event of a short squeeze (assuming trading volume remains close to average, which it almost never does during a short squeeze).

Short Interest Ratio Formula

Short Interest Ratio = Short Interest / Average Daily Trading Volume

What Happens After a Short Squeeze?

Once a short squeeze peaks, it is common for many investors to “ring the register” by liquidating their positions relatively quickly. After all, the rapid rise in price caused by a short squeeze is somewhat artificial—usually, there has been no major change in the underlying company’s fundamentals—so most savvy investors sell while the selling’s still good.

For this reason, the price of a stock that has just peaked during a squeeze tends to fall somewhat rapidly. How far (and quickly) it falls varies from case to case, but it almost always does. Investors who liked the stock before the squeeze are likely to sell at the peak then buy back in once they think the stock has fallen back down to a reasonable price level. Those who were simply along for the ride may not buy back in at all.

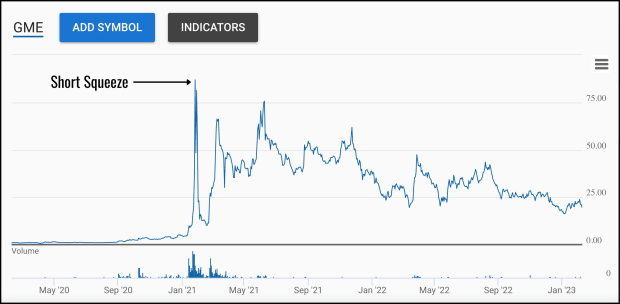

Short Squeeze Example: Gamestop

In one of the most notorious and publicized short squeezes of all time, the stock of video game retailer Gamestop exploded from around $17 per share in early January 2021 to an intraday high of about $483 on January 28th. By mid-February, the stock had fallen to around $40 per share.

This is a particularly notable example of a short squeeze. Gamestop’s brick-and-mortar retail business model was facing a multitude of challenges including a major decline in in-person shopping due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and a general shift toward online-only sales in the video game industry.

Despite a plan to restructure and prioritize digital sales, institutional investors were not optimistic about the retailer’s prospects—so much so that the stock’s short interest reached around 140%, meaning far more shares had been sold short than even existed as float on the open market.

This meant that if a squeeze did occur, the results could be devastating for the hedge funds and other players that had bet against Gamestop. The high-risk stock-trading subreddit, r/wallstreetbets, which often focused on “meme stocks” like Gamestop, saw to it that this is exactly what happened.

u/DeepFuckingValue, a popular user of the messageboard, had already been investing in GME call options, believing the company to be undervalued, and once discussion of the massive short interest in Gamestop began to dominate the subreddit, its users rallied together to buy shares, driving up the price and forcing hedge funds to capitulate by scrambling to buy back shares to cover their short positions.

By the end of January, Melvin Capital, one of the major funds that had shorted GME, had lost 53% of its value. On January 26th, reports claimed that short sellers had taken $6 billion in losses as a result of the squeeze.

A Timeline of Major Short Squeezes

- 1923: Piggly Wiggly (~50% increase in share price)

- 2008: Volkswagon (~150% increase in share price)

- 2012: Herbalife (~33% increase in share price)

- 2020: Tesla (~743% increase in share price)

- 2021: Gamestop (~1,500% increase in share price)

How Can Investors Identify Stocks That Are Ripe for a Short Squeeze?

Any stock with high short interest (let’s say, 30%+) and relatively low daily trading volume (i.e., a high short-interest ratio/days-to-cover) could potentially be well-positioned for a short squeeze, but this alone doesn’t mean it will happen. In order for a short squeeze to occur, a stock with high short interest needs a catalyst to drive its price up enough to convince at least some short sellers to cover their positions.

One way traders try to guess at which stocks might experience a price increase is by looking at the relative strength index (RSI), a technical indicator that many believe reveals whether a stock is “overbought” or “oversold.” The common wisdom states that an RSI below 20 indicated oversold conditions, which means the stock in question could rise in price in the near term.

Do Short Squeezes Occur in Crypto?

A short squeeze can theoretically occur with any tradeable asset that can be short-sold. Funds can and do short-sell crypto assets, and just like with stocks, if enough funds are short a particular cryptocurrency, and that currency’s price goes up unexpectedly, a short squeeze can occur.