It's true that AI AF can now recognize and track our subjects probably even before we've decided what we want them to be, and stacked sensors and high-speed processors allow massive burst speeds and ultra-fast electronic shutters. But the basics: resolution, ISO performance and dynamic range, don't seem to have moved on for years.

I would make a terrible camera salesperson. I would tell customers that the camera they've got is actually quite good, or that the new model they're considering does what the old one does but for a lot more money.

I have a drawer full of cameras, some brand new, some a few years old and the oldest is 12 years old. They are all good, or I wouldn't keep them. I have sold many newer cameras and kept many older ones.

This isn't just me saying this. Figures from DxOmark and our own historical lab testing data prove it – new cameras are not getting any better. Some of the best DSLRs and best mirrorless cameras for stills photography were made years ago.

If this is how it's going to be, I suspect there will be a lot of photographers out there who, like me, will continue to use 10-year-old cameras alongside new ones. Or just not buy new ones.

Rod Lawton

I will concede that ISO performance has improved. Faster readouts and better processors have certainly made a difference.

But it's dynamic range that I care about, and this has gone absolutely nowhere. Ten years ago we thought we were doing pretty well to find a camera that could hit over 12EV of dynamic range. Today we still do, and many new cameras fall short.

Much of my photography is shot in dramatic high contrast lighting, and I spend much of my time editing raw files to try to bring up shadow detail or recover blown highlight detail. And I still lose shots where one or the other has been clipped and is unrecoverable even from the raw data.

Why dynamic range is difficult for sensors

Dynamic range is limited by the photosite 'wells' on the sensor. With very high light levels these fill completely and become 'saturated'. They can't record any more highlight detail beyond that, so your highlights are clipped.

At the other end of the scale, the photosite may record such low light levels that they become indistinguishable from the random electronic noise, or 'noise floor' generated by the sensor itself. This means you get areas of solid black with no detail, or detail so faint and noisy that it looks terrible if you try to bring it out and doesn't really count as detail at all.

There doesn't seem to be any way round the basic physics of photosites, and the old-school method of merging multiple exposures HDR-style is just too clunky for everyday use. But it occurs to me that modern electronic shutters and computational processing might just provide a solution.

Could electronic shutters help dynamic range?

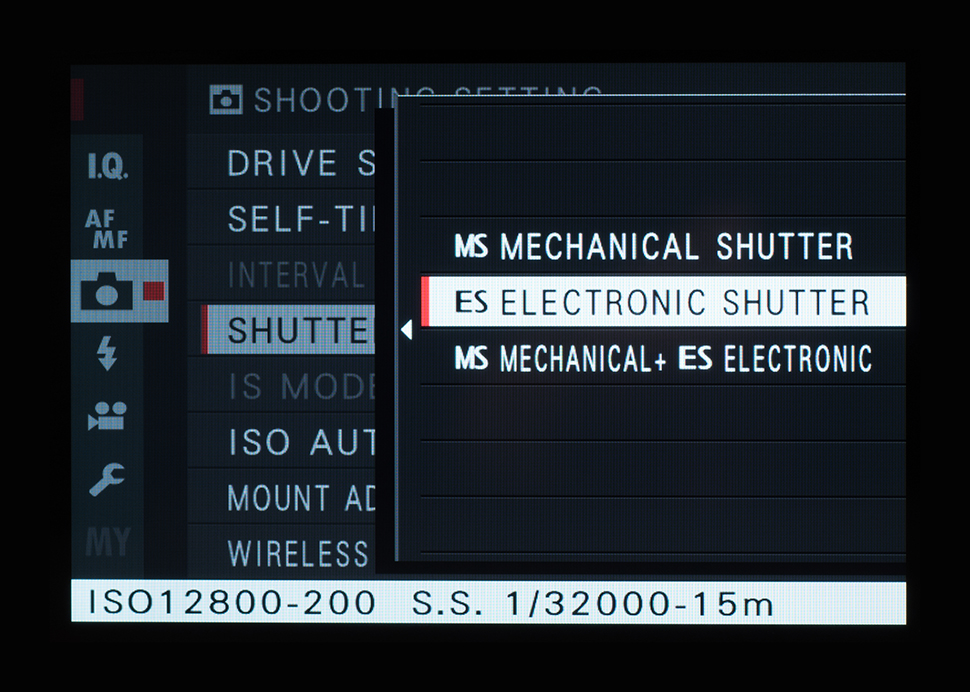

Electronic shutters work... well... electronically. There are no moving parts and there seems no reason why a second 'electronic' exposure shouldn't take place instantaneously after the first. Let's imagine the first exposure is the main one and the second is much shorter so as to capture much higher brightness levels without clipping. Then, surely, the camera's processor could merge these two exposures into a single high dynamic range file?

I don't want any fancy HDR tonemapping – I'd be be happy with a simple 'flat' image that needed processing later, just like log capture in video.

I think it's technically possible, perhaps even easy, but I'm not sure there's enough interest in stills photography for even a modest technical advance like this.

And if this is how it's going to be, I suspect there will be a lot of photographers out there who, like me, will continue to use 10-year-old cameras alongside new ones. Or just not buy new ones.

More opinion pieces by Rod Lawton:

- My 12 best and worst bits of camera gear ever

- Don't throw money at the 'best' lenses. Get the right ones instead

- I can't understand how taking photos got so complicated!

- I finally accepted camera metering systems are past their use-by-date

- I'm told the optical viewfinder is dead. We did that. It's our fault