“School SUX!”

We’ve all heard it and some of us have felt it. It’s such a common sentiment that parents and teachers might be tempted to dismiss it. After all, school is good for you! Like vegetables. It is something you have to have, whether you like it or not.

But does the intrinsic “good” and compulsory nature of school education mean we should ignore students who say they don’t like it? Or that we shouldn’t try to make it more palatable?

Feeling positive about school is associated with higher attendance, better classroom adjustment and engagement, and higher academic achievement.

Students don’t have to love school to experience these benefits. Even those who like school will dislike aspects of it: subjects they aren’t good at, having to get up early, lack of tuckshop options, and so on.

But, for some students, dislike for school can become pervasive – they dislike almost everything about it.

Some of these students may drop out of school, which has serious implications for their future job prospects, financial security and quality of life. So, yes, it matters a great deal if students don’t like school and it’s important to know why, so we can do something about it.

How did we research dislike for school?

Our recent study investigated associations between school liking and factors that previous research suggests make students more likely to stay in school or leave: teacher support, connectedness to school, and the use of detentions, suspensions and expulsions.

Our aim was to learn how we might be able to improve schooling from the perspective of students who like it the least. We surveyed 1,002 students in grades 7-10 from three complex secondary schools. These are the grades and types of schools with the highest suspension and lowest retention rates.

We wanted to find out how these students feel about school and teachers, as well as their experiences of exclusionary discipline, and whether there were important differences between those who said they did and did not like school.

What did we find?

The good news is that two-thirds of our study sample said they like school. Almost half of these students said they had always liked it. One of them said:

“Love it. I’d prefer to live at school. Like, if Hogwarts was an actual place, I’d go there.”

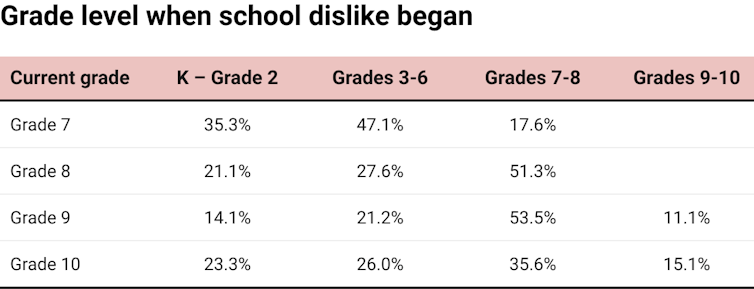

Worryingly, one-third of students said they do not like school. Although school liking was highest in grade 7, most students indicated their dislike began in the transition to high school.

“Yeah, it was probably as soon as I hit high school. Year 7 things got a lot harder.”

This dislike appears to increase over time, with grade 9 having the highest proportion of dislikers. These patterns correspond with suspension rates, which double in grade 7 and peak in grade 9.

What do students like and dislike most?

Our suspicion that students in these two groups like and dislike different things about school proved correct. While “friends” was the most-liked aspect of school for both groups, a much higher proportion of school likers than dislikers chose “learning”.

“I feel like every day I go to school, I just flex my knowledge. I like to learn. Learning’s alright.”

By contrast, a much higher proportion of dislikers chose “breaktime” as their most-liked aspect. The attraction became clearer through interviews:

“What do you like most about school?” […] “Break. So I get to see my friends.”

A similar pattern emerged for the least-liked aspects of school. A much higher proportion of dislikers than likers selected schoolwork, teachers and discipline policy as the aspects they disliked most.

“Pretty much work, because they give you all the assessments and expect it to be done so quick […]”

These findings are fairly intuitive and resonate with previous research with students with a history of disruptive behaviour who also nominated schoolwork and teachers.

The previous study found an interesting connection between the two. Students who find learning difficult will often clash with teachers whose job it is to make them do their work. Some teachers are kinder and more supportive in how they do that than others.

High school is especially difficult for these students because they have to navigate more teachers and are not good at “code-switching” to meet diverse rules and expectations.

“It was hard because you go from having a teacher the whole term who would let you do stuff and then if you tried to do that in another class, it would just be like no, you can’t do that. Yeah, and they just yell at you.”

Students who clash with teachers also tend also to experience exclusionary discipline. In our sample, not liking school was significantly associated with having received a detention, suspension or expulsion in the past 12 months. Forty-one percent of dislikers reported having been suspended (versus 14% of likers).

Our analyses also found large differences in students’ ratings of teacher support. Dislikers provided lower ratings on every item.

The highest-rated item for both groups was: “My teacher always wants me to do my best.” The lowest was: “My teacher has time for me.” The largest difference between groups was for “My teacher listens to me.”

What can schools do?

Relationships between teachers and students can be improved and educators do not have to wait for governments to act. A simple start would be for school leaders to implement student-driven school change to address issues from the perspective of all students, but especially those who say they least want to be there.

As for government policy, the findings from our study highlight one possibility for consideration. When Queensland shifted grade 7 from the primary phase to the secondary phase in 2015, steps were takens to better support children in their first year of high school. Support included a core teacher model, when one teacher takes the same students for English and humanities or maths and science, reducing the number of teachers that students have to navigate, and dedicated play areas for grade 7 students to help reduce anxiety.

The findings from our study of three Queensland secondary schools suggest that initiative may have had some success for up two-thirds of grade 7 students at least. Yet, if school liking declines in grades 8 and beyond, mirroring the rise in suspensions, is it not time to consider whether grade 8s and 9s may benefit from more intensive pastoral care?

We could always ask them!

Linda J. Graham receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC), the Queensland Government and the Spencer Foundation.

Jenna Gillett-Swan receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the Queensland Government.

Callula Killingly and Penny Van Bergen do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.