The European Space Agency’s Hera spacecraft is on its way to check out the damage NASA’s DART mission did to an asteroid called Dimorphos.

Hera launched aboard a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral on Monday, just days ahead of Hurricane Milton. While the monster hurricane sweeps across the middle of Florida, Hera will be beginning a two-year journey past Mars and out to the asteroid belt. The mission’s goal is to help us understand how to prevent a different kind of natural disaster: an asteroid impact.

So You Crashed Into an Asteroid — Now What?

When Hera reaches Didymos and Dimorphos in December 2026, it will send home the most detailed information so far about humanity’s first attempt to deflect an asteroid from its path. Hera carries 11 scientific instruments, which it will use to measure how big a dent NASA’s DART spacecraft left in the smaller asteroid, Dimorphos, when it plowed into the asteroid’s surface in September 2022. The mission will also measure the exact mass and makeup of Dimorphos, something scientists here on Earth are only approximately sure about even after smacking a 1300-pound spacecraft into it.

By combining those two key pieces of information, researchers will learn how asteroids of different types react to having heavy chunks of metal smash into them at high speeds — which could one day save millions of lives, if space agencies can translate that information into designing missions to knock any menacing near-Earth asteroids off their collision courses with Earth. (That’s not the only idea that scientists are working on; a recent study suggested that x-rays from a nuclear explosion could also nudge an asteroid away from Earth.)

2500-foot-wide asteroid Didymos was never a threat to Earth, and neither was poor little Dimorphos, the 500-foot-wide clump of rocky debris that orbits Didymos. But the system was a perfect target for DART, a mission to test whether we could actually knock an asteroid off course by hitting it with a spacecraft. The answer turned out to be yes: DART hit Didymos hard enough to change its orbit around Dimorphos by about 30 minutes.

What we can see from Earth suggests that a lot of that change came from the plume of ice and vapor blasted out of the asteroid by the crash — not from the momentum of DART smacking into its surface at 13,000 miles an hour. That’s important to understand, because it can help mission planners figure out the right size, speed, and angle to hit the next asteroid with. For the same reason, it’s important to understand exactly what Dimorphos is made of and how it’s put together. Astronomers are fairly sure that Dimorphos is what’s called a rubble pile asteroid, meaning that it’s mostly big boulders of rock, with dust in between them, held together by gravity but not actually melded into one solid chunk of rock. And that could explain why DART seems to have actually changed Dimorphos’s shape instead of just digging a crater.

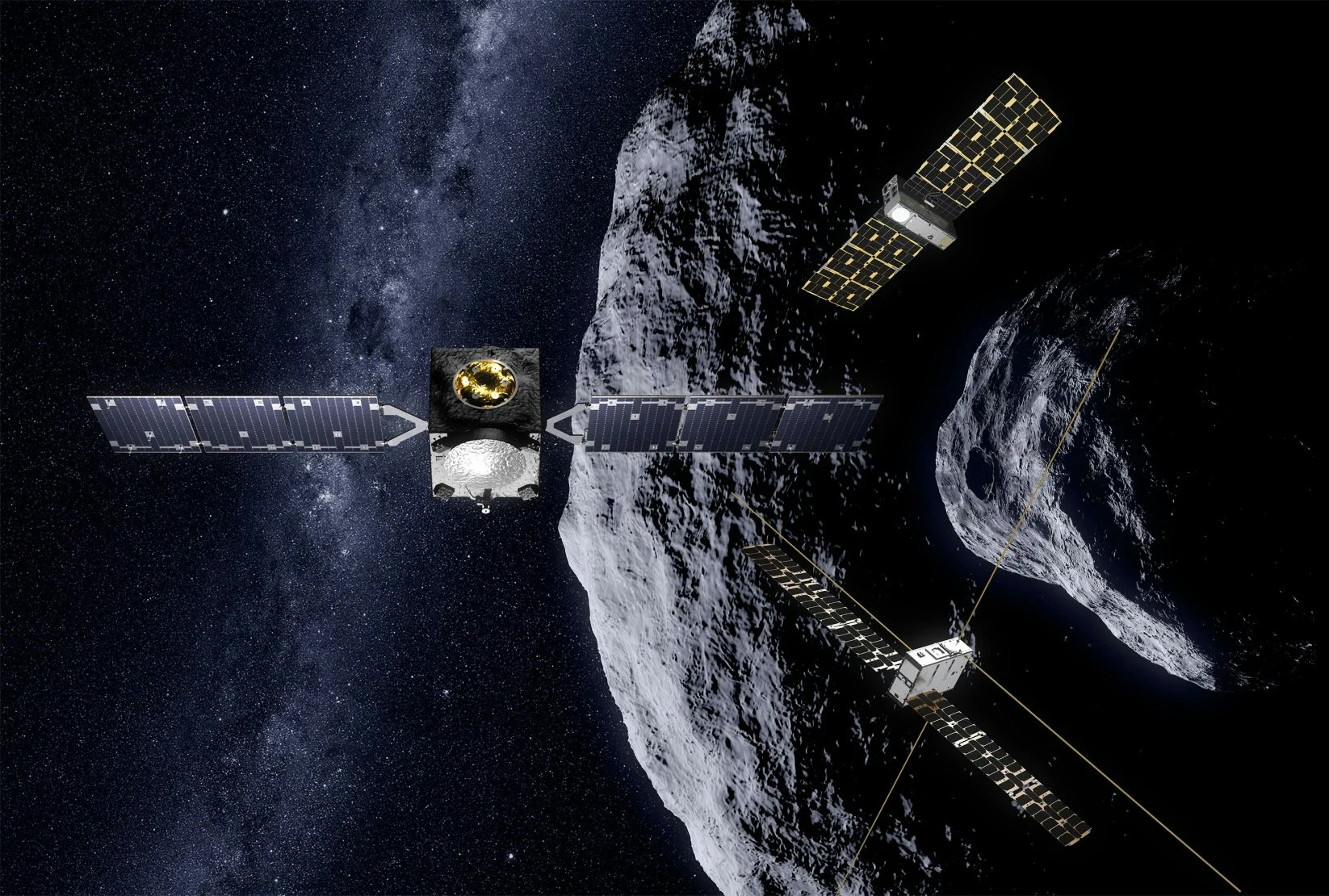

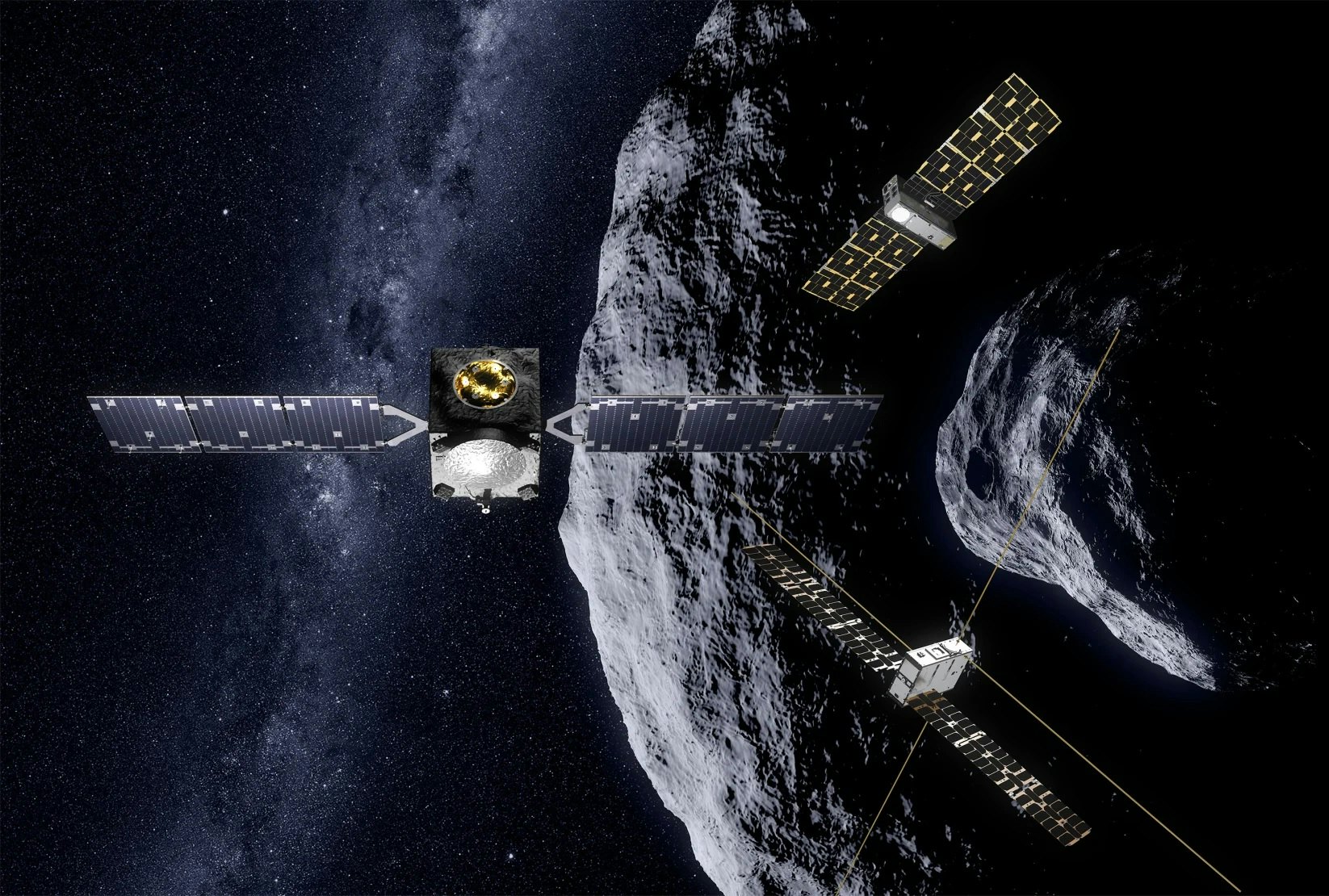

One of Hera’s main goals is to get a clearer answer to that question. To accomplish that, the spacecraft is packed with 11 scientific instruments — and like asteroid Didymos, Hera has satellites of its own: two miniature spacecraft about the shape and sizes of shoeboxes, called Juventas and Milani. (Milani was named in honor of the late mathematician Andrea Milani, who developed a computer system to calculate the chances of any given asteroid eventually posing a threat to Earth.)

Together, the three spacecraft will spend several weeks in orbit around the pair of asteroids, eventually swooping within half a mile of Didymos. At the end of the mission, Hera will attempt to land on Didymos, while her two little cubesats try to set down on Dimorphos — all without landing gear, so it’s going to be more like a series of very slow, careful crashes, which engineers hope the spacecraft will survive.

If asteroids could muse, Dimorphos might be thinking, “Oh, dear, not again.”