David Hockney’s new exhibition finds beauty in the most local of places: the home. His new series, 20 Flowers and Some Bigger Pictures, is about the pleasure of looking intensely at what is in front of us.

At home in Normandy during lockdown in 2021, Hockney turned what he describes as his ability to “see things clearer and clearer”, into drawing the 3D delicacy of flowers in a vase on the flat surface of his iPad.

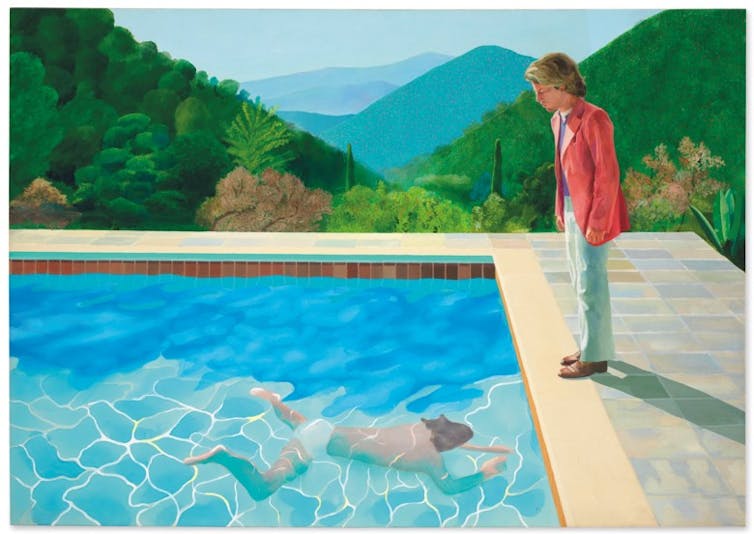

One of Britain’s most significant 20th-century artists, Hockney was born in Bradford in 1937. He became fashionable in the swinging London of the 1960s, holding status as an exotic northerner against the capital’s urbane backcloth. After a visit to southern California in 1964, he became popularly associated with this period with his homoerotic stylised swimming pool paintings.

Still artistically prolific at 85, sartorially elegant and with dry humour, he recently declared he was “bored with wellbeing” instead defending the right to pleasure – in his case, smoking cigarettes. Hockney has been based in Normandy since 2020, choosing to live in northern France for the quality of light in the region and as a peaceful place to work.

Art and upheaval

Hockney spent much of the COVID lockdown in near isolation in his 17th-century country home in Normandy. He used the time to watch and record the changing seasons on his iPad, with much of his work from this time offering inspiration for his latest exhibition.

This can be seen in 30th May 2020, From the Studio, one of the larger works in his new exhibition, 20 Flowers and Some Bigger Pictures exhibition. This piece clearly demonstrates Hockney’s ability to see texture, colour and form within the four walls of the home and the surrounding space of the garden and outbuildings.

Hockney’s works in 20 Flowers mark a return to his obsession with the act of looking. His centrepiece for the exhibition, 25th of June 2022, Looking at the Flowers (Framed), is a photographic drawing of himself times two, looking at a wall filled with his framed still lifes.

From a series of individual photographs, Hockney constructs a seamless panorama that defies the natural parameters of time and space. This relates to Hockney’s disappointment with photography, a medium he has spoken about many times as being limited to only capturing an instant in time from a single point of view.

For Hackney, the artist’s eye holds something more special. A celebrated draftsman who has been trained to look, Hockney argues that “we see with memory” and with our emotions. Indeed, artists have the potential to document how places and objects affect us and move us emotionally.

Hockney’s north

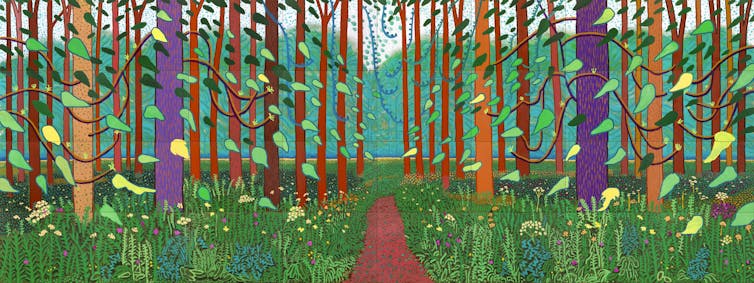

Hockney’s body of work has always maintained affection for visual beauty in place – whether at home or in landscapes. His 2012 series, A Bigger Picture, peeled open a part of Yorkshire relatively unknown, even to northerners: the East Wolds, which are low hills spread across the East Riding of Yorkshire and north Yorkshire.

In 1997 Hockney moved back to the Yorkshire coast when his friend Jonathan Silver was dying of cancer. Drives to Bradford took him through the small villages dotted through the rolling Wolds.

My first view of these paintings was on TV in 2010, when I watched Bruno Wollheim’s documentary David Hockney: A Bigger Picture and saw the suite of paintings called Woldgate Woods unfolding the changing seasons in crisp high definition. I found myself in my lounge, incredibly moved by the exquisite atmosphere of woods from May to December. It was then that I decided to research how other people from Yorkshire responded to this series of works.

Historically landscape beauty in art has more usually been associated with the home counties in the south of England than with Yorkshire. But what my research found was that people used Hockney’s paintings to transform their north from somewhere often portrayed as dour and grimy into a place of untapped beauty. Delighted by his prodigal return from the US as a “Bradford lad”, they saw him as a cultural ambassador promoting the north’s place in the galleries of the metropolitan centre.

Importantly, I found that many people held an appreciation of curating Hockney’s prints within their own homes, rather than seeing his work in a gallery setting. Woven into the routine of moving through corridors and rooms, his prints could be walked past, looked at and engaged with by their owners and other family members in the relaxed and intimate space of warm, domestic familiarity.

In this way, Hockney’s works acted like a form of art kinship within the home. And I believe that these new works can be used by viewers in the same way.

The artist has in the past spoken about the act of observing his first still life, “it looked very beautiful to me. Other people commented on it, it seemed to jump off the wall.” In his creations, I feel Hockney is asking us to look and see the detail. He may even be asking us to draw and paint it ourselves. Either way, his fresh, vibrant drawings offer beauty to help us cope in difficult times.

Lisa Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.