The United Nations has warned that the war in Ukraine could create “the biggest refugee crisis this century.” Two and a half million people have already fled.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world sits watching the war on screens, which can promote empathy but also can lead to helplessness and distress.

There’s another way to try to understand refugees’ experience. Alongside the reality of desperate people fleeing danger is a rich history of classic texts about characters seeking protection or new lives.

As a professor of humanities and law, I have spent the past few years delving deeply into what classic literature has to say about the challenges of fleeing persecution. From Odysseus and Dante the Pilgrim to Frankenstein’s monster, many familiar characters encounter obstacles well known to contemporary refugees.

These stories can’t replicate what it’s like to experience bombs and shells raining down on Syria, Ukraine or Yemen. But they may help readers identify with characters they already know, which may in turn create empathy and compassion for refugees.

Sharing the story

One text worth recalling in this regard is the Book of Exodus, and in particular the scene in which God appears to Moses at the burning bush.

God has been watching the Israelites’ suffering as slaves in Egypt, he reveals to Moses. The Almighty wishes to intervene – and calls upon Moses to act as his emissary.

“I will send you to Pharaoh, and you shall free My people, the Israelites, from Egypt,” God commands.

Moses’ initial reaction is not to obey, but to question. “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and free the Israelites from Egypt?” he asks. He fears that his poor speaking skills render him ill equipped to fulfill God’s will. “I have never been a man of words,” he protests; “I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.”

His hesitation is a reminder that vulnerable migrants often have nothing with them other than their own story – a story they may have to tell in a language that is not their own. Ukrainians who are currently in flight, for example, will have to explain themselves adequately. Being able to tell their story in the right way, to the right people, will be crucial to their very survival.

Moses is also unsure whether God really is who he says he is. Can this great power be trusted? Moses wonders. As refugees flee their home countries, they too may wrestle with whether to trust people and officials from powerful institutions offering aid, like host country officials, or representatives from United Nations agencies or nongovernmental organizations.

The land of milk and honey

To persuade Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, God promises the Israelites not just protection, but a better life: “I will take you out of the misery of Egypt … to a land flowing with milk and honey.”

Historically, many people fleeing home are escaping not war or persecution, but poverty – though the lines between refugees and so-called economic migrants are getting blurrier. Those who wish to deny entry to refugees or undocumented migrants often describe them as “parasites” or “illegals” who are leaving their homes to reap the milk and honey of others’ lands.

John Steinbeck’s novel “The Grapes of Wrath” tells the story of desperate American families during the Great Depression fleeing the Dust Bowl droughts that devastated their crops. They are “people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness is there.”

They dream of a new paradise, and of plenty. Tom Joad, one of the book’s key characters, provides a vision of the life that he imagines in California: “Gonna get me a whole big bunch of grapes off a bush, or whatever, an’ I’m gonna squash ‘em on my face an’ let ‘em run offen my chin.”

It may be a pipe dream, but what option do these vulnerable migrants have? Like millions of people in places like India, the Philippines or Bangladesh, they have been internally displaced because of natural disasters and climate change. The only way to safety is forward.

“How can we live without our lives? How will we know it’s us without our past?” Steinbeck writes. “No. Leave it. Burn it.”

Leaving paradise

No matter how great the persecution, not everyone will flee in search of protection. Home still provides us with a sense of rootedness; home is where we speak the language; home is where we have friends and family; home is filled with familiar landmarks.

And for people fleeing Ukraine, the decision to leave means enduring huge lines, freezing cold and administrative barriers – particularly for non-Europeans who resided in Ukraine, such as Indians and Africans, who have faced discrimination.

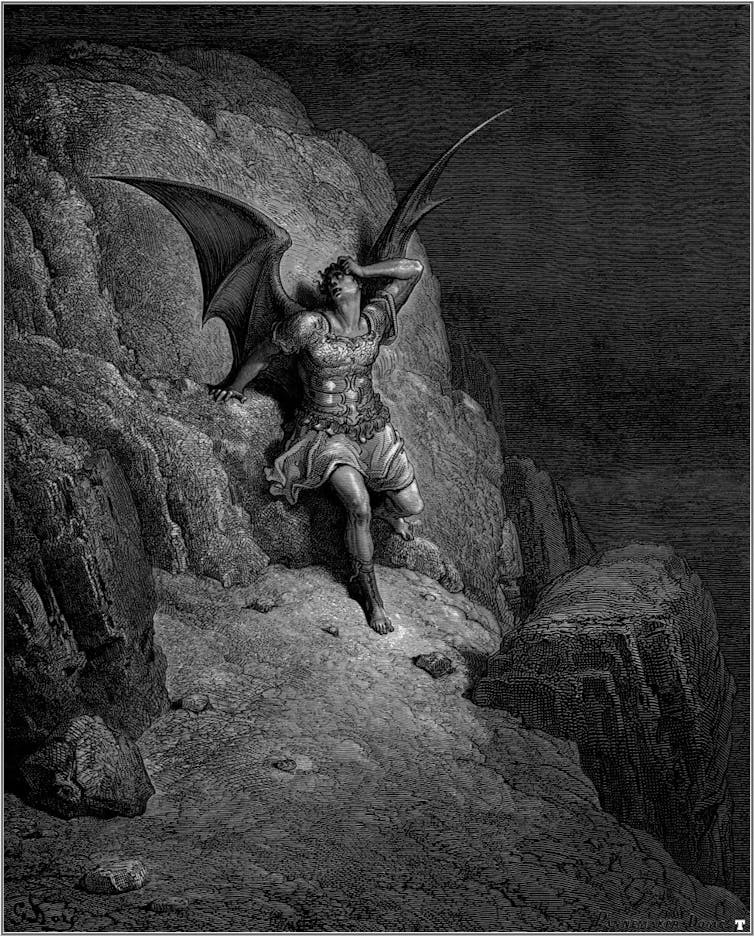

John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” is one of the great stories about massive displacement and the effort to survive in an inhospitable environment. This 17th-century epic poem describes two acts of exile: rebel angels’ expulsion from heaven, and Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

After the war in heaven, when Satan attempts to lead one-third of the angels in rebellion, God’s retribution is swift and horrible. Satan’s followers are “hurld headlong flaming from th’ Ethereal Skie / With hideous ruine and combustion down / To bottomless perdition, there to dwell,” in Milton’s description.

Even Satan, who actively led the uprising, was filled with the despair at all he’d lost: “Now the thought / both of lost happiness and lasting pain / torments him.”

These terrifying lines hold one of Milton’s masterpiece’s most important insights for migration crises today. Through expulsion, these fallen angels have lost everything they hold dear, and now they are condemned to hell. Their pain is mixed with “obdurate pride” and “stedfast hate.”

If contemporary refugees are unable to find a new sense of belonging and opportunity, then their frustration and trauma sometimes turn to resentment and radicalization. From Ukraine and Yemen to Afghanistan and elsewhere, many desperate people are in need not just of assistance, but long-term solutions that provide a chance for them to rebuild their lives.

These examples from classic texts intimately depict refugees’ challenges through characters who have peopled our imagination. Perhaps this same process of creative association with well-known stories of displacement can help inspire ways to help vulnerable migrants in our midst.

Robert F. Barsky receives funding from Rockefeller Foundation; Vanderbilt University; SSHRC; CRC

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.