Imagine … eco-tourists enjoying views of undisturbed whales and dolphins, watching them doing what comes naturally.

This is ultimately what we all wish to see when spending time in nature watching animals. We can achieve this by using quieter boats.

But why do we need quieter boats? Whales and dolphins primarily use hearing to sense their surroundings (rather than sight like humans do). Sound travels almost five times faster underwater than it does in the air, so it’s an important sense for whales. They rely on sounds to communicate, navigate, feed and detect predators.

Our new research confirms noise from a boat watching whales at a distance of 300 metres can still disturb them. And watching whales involves a lot of boats and millions of tourists each year. This multi-billion-dollar industry is active in waters off more than 100 countries. The Australian whale-watching industry is one of the biggest in the world.

Because the industry actively seeks out whales and dolphins, using quieter boats should be a priority. Yet current whale-watching guidelines, including Australia’s, do not include noise levels. They should.

As the whale-watching season begins in Australia for humpback whales and southern right whales, we offer tips here for individual operators to reduce noise from their boats.

Read more: Thar she blows! An expert's guide to whale watching 101

How does noise affect whales and dolphins?

Besides income for local communities, whale watching has education and conservation benefits if tourists are inspired to care for the environment.

Despite these benefits, watching whales from a motorised boat and swimming with whales can disturb their natural behaviour. For example, it might prevent them from resting or feeding, or change their breathing, swimming and dive patterns. These impacts are especially important for whales with young.

If the cumulative effects of these short-term impacts are not considered, they can lead to long-term consequences for the animals, such as population declines or leaving an area altogether.

Such outcomes are not only negative for the animals, but also for the whale-watching industry that depends on them.

Read more: Drones gather new and useful data for marine research, but they can disturb whales and dolphins

Whale-watching guidelines overlook noise impacts

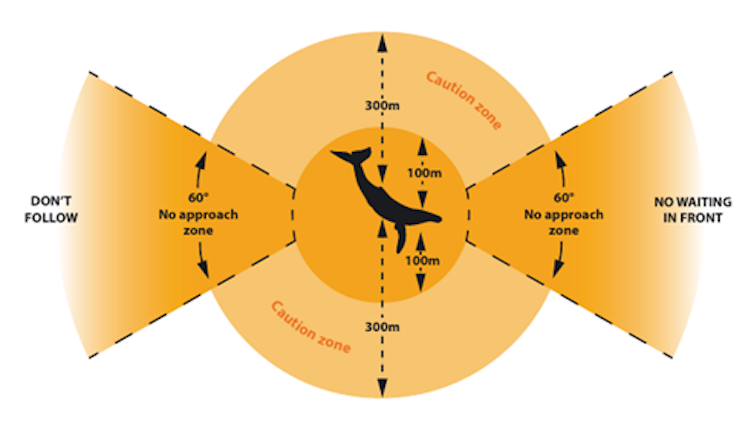

Many countries have guidelines on the boat’s minimum distance from the animals (typically around 100 metres), the speed at which it passes (typically below wake speed) and the approaching angle (typically from the side-rear). Guidelines, however, do not consider the noise level of the boat’s engine. A very loud boat is, in effect, considered to have the same impact on the animals as a very quiet boat.

Research confirms louder boat noise disturbs whales more than quiet boat noise. Boats should be as quiet as possible.

We recommend a noise threshold be added to whale-watching regulations, ideally around the volume of the natural underwater background noise. At this level, boat noise is perhaps audible to the whales but with a low perceived loudness. This change to the guidelines will help minimise disturbance to whales and dolphins.

You can see how humpback whales change their behaviour in response to low, medium and high underwater boat noise in this video from our study.

Read more: Underwater noise is a threat to marine life

What do whale-watching boats sound like underwater?

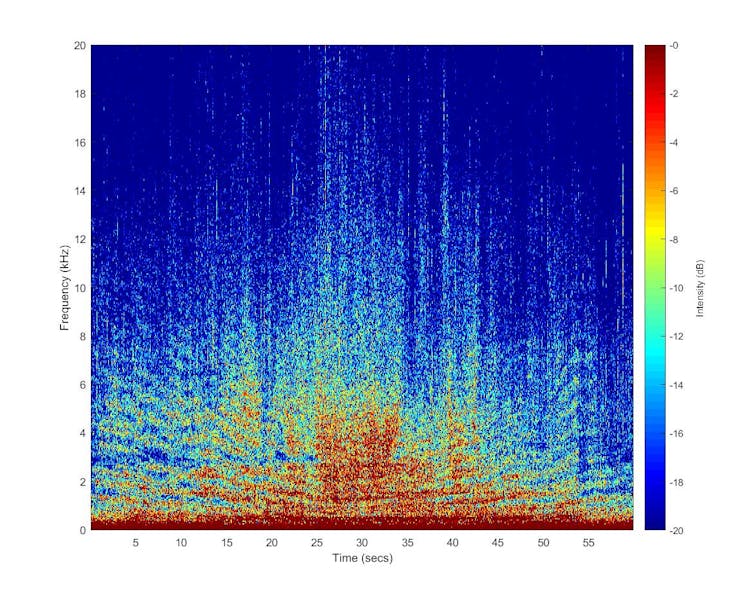

A range of different boats are used for whale watching worldwide. We have calculated the underwater noise level of whale-watching boats operating at low speeds. The quietest boat was a hybrid boat using its electric engines.

The vessel with the quieter electric engines was later used in an experiment with short-finned pilot whales. This study compared the whales’ responses to the boat’s quieter electric engines and its louder petrol engines.

What was the result? The louder engines did indeed disturb the behaviour of short-finned pilot whales compared to the quieter engines. Notably, resting and nursing of young decreased.

Ultimately, some vessels are better designed to minimise noise emissions. You can hear the quieter electric-engined boat in this recording from the study. This makes this boat more appropriate for whale watching.

Read more: Why scientists need your help to spot blue whales off Australia’s east coast

Noise when arriving and departing matters too

Having a quiet boat will reduce the disturbance to animals. However, even when a whale-watch operator adheres to current best-practice guidelines, there may still be disturbance.

This is because as a vessel increases in speed to leave the whales, it produces higher underwater noise levels. Our research shows this is likely to disturb whales. So we recommend boats maintain a slow speed when approaching and departing whales – say, less than 10 knots within 1km of the whales.

We know it is exciting to zoom off towards a breaching whale, leaving a sleeping whale behind, but the sudden increase in boat speed and noise may then disturb that sleeping whale.

5 tips to reduce boat noise

On an individual level, boat operators can easily reduce disturbance to whales and dolphins by considering the following five factors.

Speed increases noise from the propeller, so lower the speed, even when arriving/departing.

Distance: the closer a vessel is the greater the peak in noise, so keep to the regulated distance.

Gear shifts cause high-level noise changes, so minimise shifting.

Approach type to the animals can cause disturbance – driving in front of their path, for example, so drive in parallel to their path.

Movements of a boat, such as fast and erratic movements, can disturb animals, so drive consistently.

To further reduce noise, whale-watching companies can use larger, slower-moving propellers (to minimise the water disturbance that creates noise), quieter/electric engines and/or install noise absorption gear.

Both the industry and the whales will benefit from companies using quieter whale-watch boats and approaches.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.