For Navy veteran Sabrina Waller, tattoos are therapy.

Among her tattoos, she has an anchor, representing the Navy, tangled in the American flag; a paperclip; the word “peace” in graffiti-style lettering; and script that can only be read in a mirror.

As these were etched into her skin, Waller, 45, who lives in the west suburbs, says she found herself “breathing in those colors or just breathing in the pain.”

The permanent art tells the story of Waller’s complicated emotions surrounding her time serving in the Navy. Two years out of high school, Waller enlisted. She trained to work on weapons systems — a job she never ended up doing because, as she stepped aboard a ship for the first time, she was starting a deployment that, nine days in, led her into the Kosovo War.

“It was 70-something days of straight bombing over another country,” Waller says.

After doing five years of active duty, Waller left the armed forces in 2003.

Two decades later, she has found herself involved with groups that support veterans and advocate for peace.

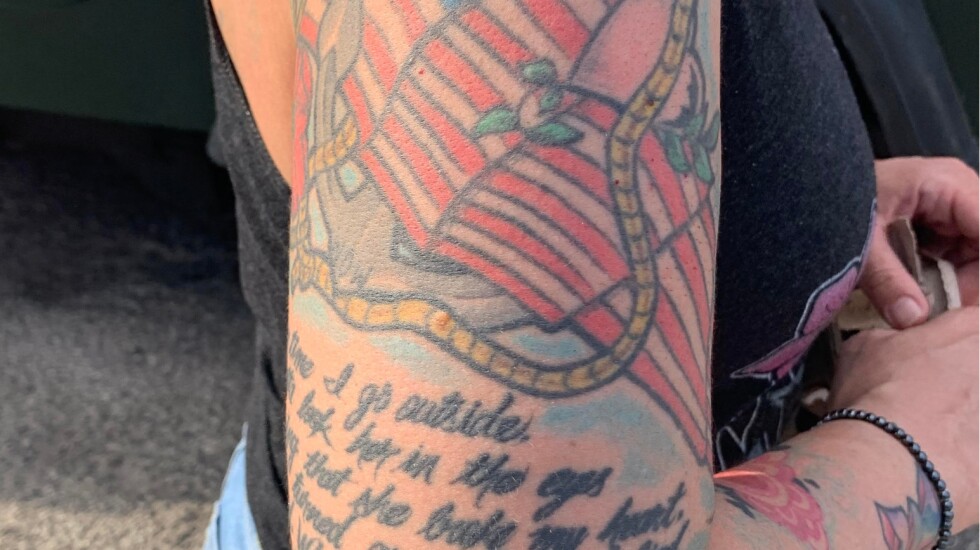

It was with one of those groups, Iraq Veterans Against the War, that Waller met an Afghanistan war veteran whose death by suicide in 2014 led her to have the lyrics of a song he’d written, titled “Soldier’s Heart,” tattooed below the American flag she already had on one tricep.

It reads, “Every time I go outside I look her in the eyes, knowing that she broke my heart and turned around and lied. Red, White and Blue, I trusted you and you never even told me why.”

“I got the flag on me,” Waller says, “thinking that, if I pounded the red, white and blue in me, I would learn and understand more to honor that and cherish that. And then Jacob’s lyrics just really wrapped it all up.”

The lyrics, along with a few of Waller’s other tattoos, were done by an artist who goes by Erie CMW at the Stained in Pain tattoo shop, 4211 N. Milwaukee Ave.

One of Waller’s tattoos, on one lower arm, has the word “peace” spelled out in blue, pink, purple and white letters and hearts that look like they were spray-painted on. Waller says the placement originally was based on where she had space. But, after getting the ink, she realized the tattoo was a sort of protection piece for her, something that would show if she needed to cover her chest.

At one point during her time in the Navy, while starting engines for pilots on the flight deck, Waller says a service member grabbed her, saying it was to put her out of harm’s way.

“It was a guise of helping me,” she says. “But there was no reason he had to grab my breasts to save me, to be my savior. Subconsciously, that’s why I got that peace sign there.”

The son of a Purple Heart Vietnam war veteran, Erie says he’s honored to offer his tattoo chair as a place for veterans to sort out their experiences.

“Vets are their own breed of people,” he says. “Their tattoos have so much more meaning than most people’s.”

The artist compared the tattoos that veterans get to memorial tattoos someone might come in for when a loved one dies.

“It’s just almost like the fear of forgetting,” Erie says. “You get that tattoo so you never forget.”

The tattoo Waller has just below her collarbone is a reminder like that. To anyone else, the block lettering might be hard to make out. But when Waller looks in the mirror, the backwards ink reads: “Maintain your military bearing.”

“When I look in the mirror, it’s something I can accept or not accept,” Waller says. “I don’t have to maintain my military bearing anymore, but I understand that training and the meaning of those words.”

Waller says she has “brain dumped” more on Erie than she has on any of her Department of Veterans Affairs therapists, having to “find the words,” to describe what she’s feeling to help him turn that into art.

Waller was able to help Erie’s father, helping him reapply for additional benefits through the VA.

“That’s the beauty of the tattoo game,” Erie says.