40 years after its 1974 release, Gentle Giant’s The Power And The Glory was remixed and mastered by Steven Wilson. to mark the occasion, the band – including the late Ray Shulman – looked back with Prog on the making of their sixth album, why the UK never warmed to them, and the band’s eventual demise.

If, as theoretical physicists speculate, there exists an infinite number of parallel universes, then there could well be an alternative Earth where Gentle Giant are one of the most respected, revered and talked-about best-selling bands on the face of that particular globe.

Although their decade-long career was not without some stylistic missteps toward the end, at in their mid-70s heyday they produced some of the most adventurous, inquisitive and fearlessly idiosyncratic music in an era already brimming with talent and innovation. If the likes of Yes, Jethro Tull and ELP constituted significant parts of the progressive movement’s orthodoxy back in the 1970s, then Gentle Giant stood slightly apart as a kind of dissident faction whose collective virtuosic grasp drove complexity and rock music in many directions – all of them away from the mainstream.

“We were a very isolated band,”’ says keyboard player Kerry Minnear. “We tended not to listen to what others were doing in the whole prog rock genre, or whatever it was called then. I suppose we were quite intrigued by what was possible musically and we went about as far as we could go. No wonder we never made any money!”

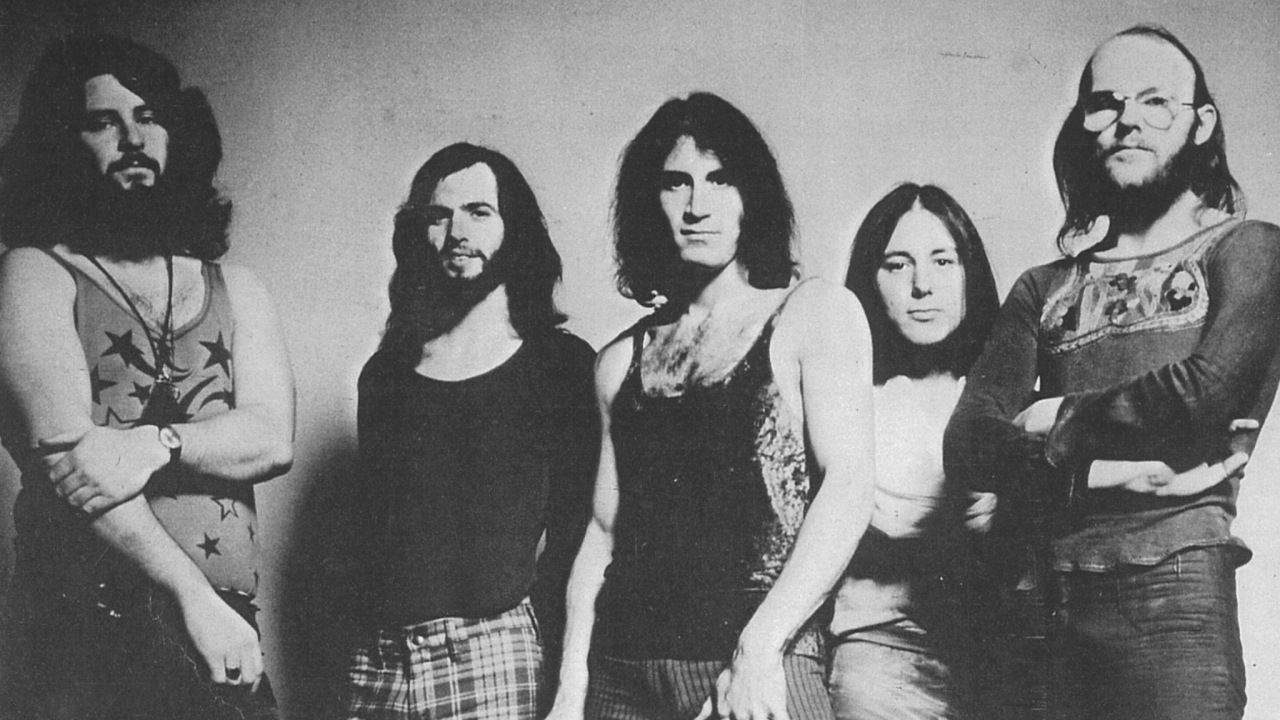

Forty years on, however, Minnear and his bandmates John Weathers (drums), Derek Shulman (vocals, saxes), Ray Shulman (bass, violin, vocals) and Gary Green (guitar), have more in common with those outfits mentioned above than they perhaps ever did – thanks to a new stereo and surround-sound remix of Gentle Giant’s sixth studio album, The Power And The Glory, by long-time fan Steven Wilson.

For some, the thought of anyone messing with their favourite album is sacrilegious. But as Derek Shulman points out, for the band it’s a golden opportunity to resolve some of the shortcomings and compromises they encountered when recording the album in the winter of 1973-74. “Because we had such a fast rate of work, I suppose we were sometimes a little too quick in deciding things in the studio,” he says.

“Looking back, we wished we’d put a bit more low-end on parts of it, or a little more on the kick drum – those kinds of things. I think Steven has improved some of the textures we’d created, embellishing the sound but staying true to the original album. He’s done a great job and I hold him in high regard for that.”

Ray Shulman, similarly impressed by Wilson’s ability to breathe new life into the sound, has added his own motion graphics to accompany the music. “They’re not meant as an interpretation of the lyrics in any way – more an interpretation of the music. In some ways it’s a bit of a lava lamp for those who buy the Blu-ray for the high-end audio. I wanted them to have something to look at while it’s playing, should they want it.”

Exploring the corruption of ideals at a political level, The Power And The Glory also examined the pernicious impact of power for power’s sake within relationships. “I think it’s the only real conceptual album that told a story from both ends of the spectrum – from the top end of society to the ordinary people – and looking at them in both an empathetic and provocative way,” argues Derek. “Even the most altruistic person can be corrupted by power. We’ve seen it time and again in politics, in the corporate world, in the music business – and even in group business as well.”

We’d all calmed down a bit.… it’s quite a mature album that’s well-conceived and beautifully executed

Gary Green

The album importantly marked a point of stabilisation in the group’s unsettled equilibrium following the struggles and difficulties culminating in Phil Shulman’s departure after 1972’s Octopus. “We did In A Glass House (1973) after Phil left and it’s quite a brittle album; we were finding our feet as a five-piece,” says Minnear.

“There wasn’t too much of a difference for me, but for Derek and Ray, who’d been in bands together way before Gentle Giant, it was probably quite a change without their brother being there. For me The Power And The Glory was the album where we truly became a band.”

Guitarist Gary Green agrees. “In A Glass House was a bit of a reaction to Phil’s departure. I think we were keen to prove ourselves, to carry on without Phil; and it’s a pretty hard-edged album, a bit spiky. As the title suggests, we couldn’t say anything without people coming down on us like a ton of bricks. By The Power And The Glory we’d all calmed down a bit. We were making music on our own terms now we’d established ourselves as a proper five-piece. It’s quite a mature album that’s well-conceived and beautifully executed, I think.”

Their unashamedly eclectic approach to making music placed them largely beyond the norms at a time when creativity and experimentation were, if not actively encouraged, then at the very least tolerated by the record companies and audiences of the day.

Capable of rocking out one moment and then executing a breakneck turn into medieval hocketing the next, Gentle Giant could never be accused of sitting back and taking things easy. Their alarming elasticity with pitch and timbre was as confrontational as it was unconventional, and above all else showed a band committed to breaking out way beyond their own individual comfort zones.

The UK thought we were uncool, not hip, pretentious or whatever… in Rome we had 20,000 people

Derek Shulman

“We put ourselves first, which probably sounds very selfish – but we pushed more for ourselves than anyone else,” says Derek. “We were pretty intense, with an intense work ethic to match, only because we wanted to excel for ourselves musically. We loved to write and record and to play music for each other first; hopefully we’d impress each other, the individual members of the band. And then when it was rehearsed to put it into a recording, and then hopefully went on the road, the people who listened would enjoy what we’d done. It wasn’t just a hobby. It was our life.”

That sense of Gentle Giant as a band that ‘could-have/should have’ is present when appraising their ambitious approach. Though they never won over significant numbers of UK punters, their near-relentless touring in Northern America, bolstered by support slots with Jethro Tull, gained them a substantial following. Though Glass House was initially denied a release by their then-US label, CBS, Power saw them make inroads into the American charts, peaking with Free Hand in 1975 – which hovered inside the Billboard Top 50.

“It’s always been a mystery to me as to why we never went over as well in the UK as we did elsewhere,” says Green. “We did okay playing big theatres and other large venues, but we largely we went unnoticed. The press in Britain love to build you up and tear you down – of course, in our case, we never got built up! They never took a shine to us. There was a sense that we were ‘pretentious,’ and that was the last thing on our mind, honestly.”

We lost our way a bit toward the end, I think. It became less interesting

Kerry Minnear

It’s a point that still irritates Derek to this day. “For some reason, the UK thought we were uncool, not hip, pretentious or whatever, yet we were headlining fairly big venues in Europe – in Rome we had 20,000 people. In North America, Canada in particular, we were a fairly big group who would play to 10,000 and 20,000 people at each show.”

Ironically, that success sewed the seeds of their eventual downfall. As progressive rock’s heyday began to recede, the band’s fiercely insular approach and gloriously defiant non-conformist attitude began to soften. “I think Glass House, Power and Free Hand were our pinnacle,” says Ray. “After that, with The Missing Piece, Giant For A Day! and our final album, Civilian, we kind of floundered and didn’t quite know where to go.

“I think we were totally torn between trying to make it big and making our music more crossover but failing most of the time. I think that happened because we became conscious of what we were doing. Prior to that we worked on instinct and didn’t think about anything other than the music itself.”

Minnear shares Ray’s assessment. “We lost our way a bit toward the end, I think. It became less interesting. When I look back on it now I don’t often listen to those later albums, to be honest. But the early ones I still find are great.

“I’d absolutely regard Power as a very special album. It’s got an awful lot that the band can be pleased with.”