It’s March 9, 1978. The ritzy stage of the Scarborough Penthouse lookslike something out of The Price Is Right: curtains made out of multi-coloured strips of aluminium foil drape over a modest backline of amplifiers, there’s a mirrorball hanging from the ceiling, there’s glitter on the walls. But there’s no sense of pomp and ceremony, just a taste of stale beer and a whiff of pie and chips. There are maybe 100 people here for only the fourth ever gig by Whitesnake, fronted by the dynamic and thrusting David Coverdale. Cum on down…

To those more familiar with the modern-day, turbo-charged Whitesnake, this band from the late 70s would be unrecognisable. Coverdale takes to the boards wearing cheap T-shirt and jeans, more Millets than Moschino. He’s pale-faced and chubby-cheeked; his mane of dark brown hair is untamed, unteased, unbleached.

Micky Moody sports a Zapata moustache and his trademark trilby; he’s an old-school guitarist from Middlesbrough, Coverdale’s neck of the woods, who’s earned his chops in Juicy Lucy and Snafu. Moody went to school with Free’s Paul Rodgers – and formed a band with him, before Rodgers’s voice had even broken.

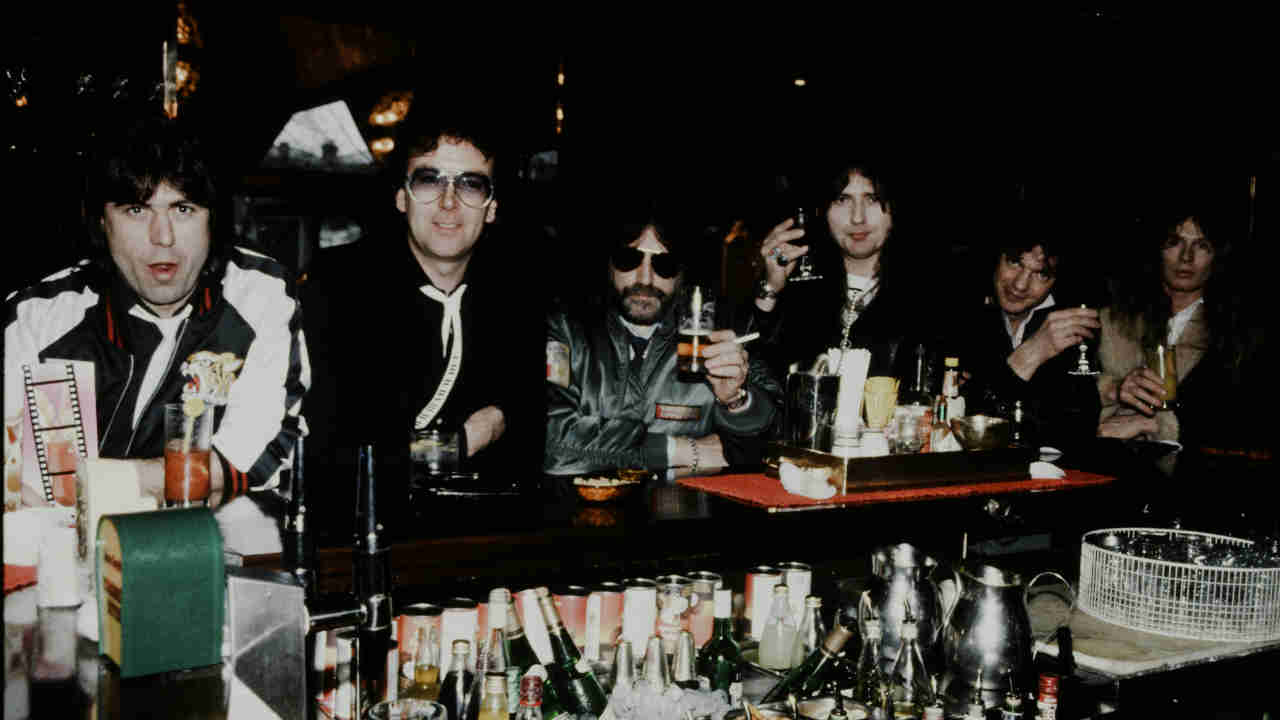

Then there’s fellow guitarist Bernie Marsden, small, smiling and stocky, ex- of UFO, Wild Turkey, Cozy Powell’s Hammer and Paice Ashton Lord. (Or ‘Plaice Haddock Cod’ as Coverdale calls them; this being a good-natured jibe at the singer’s former band-mates in Deep Purple, drummer Ian Paice and keyboardist Jon Lord, who created PAL with Tony Ashton.) And who’s this on bass? Neil Murray, who this writer last saw playing complicated jazz-rock-fusion in Colosseum II with Gary Moore and Jon Hiseman. On keyboards there’s Brian Johnston, and on drums there’s David ‘Duck’ Dowle, both ex-Roger Chapman’s Streetwalkers.

A stellar cast? Perhaps not. But boy, can they play – and sing, especially sing – the blues.

The highlight of Whitesnake’s set is Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City, a song made famous by Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland. Played at a restrained pace, it’s moving, deliberate, pure, intense. As Coverdale’s deep, sonorous voice echoes around the room, it raises the hackles on your neck. And then caresses them. Welcome to pre-1987 Whitesnake. One of the best blues-rock bands you’re ever likely to hear.

“Believe it or not, it wasn’t really my intention for the early Whitesnake to follow that kind of musical direction,” Coverdale says, speaking to Classic Rock in 2005. “The guys in the band, other than Micky, had no time to put any musical stamp on what was taking shape initially. It just began to develop as we played more and more together. Remember also at the beginning we had to do some Purple tunes to fill out the set.

“Micky and I enjoyed working together and got on well enough as friends at that time. He was a local musical hero of mine. I thought he had great potential. He was aware and supportive of my desire for a hard rock, blues-based, melodic rock band… with soul! He was also the antithesis of Ritchie Blackmore.”

Five years earlier, in 1973, Coverdale had quit his job as a salesman in a menswear boutique in Redcar to become the singer in Deep Purple, replacing Ian Gillan. It was a baptism of fire for this untried talent from Saltburn-by-the-sea, so it was appropriate that his first album with the band would be titled Burn.

Coverdale made one more record with the Purps – 1974’s Stormbringer – before guitarist Blackmore quit, to be replaced by American Tommy Bolin. Despite Bolin’s undoubted talent it was an ill-fated move. Come Taste The Band, released in 1975, turned out to be Coverdale’s final DP LP offering, notwithstanding the live album (Made In Europe) that followed. The singer resigned his position after a disastrous Purple gig at Liverpool Empire in March 1976, where a spaced-out Bolin froze in mid-solo and the Mk IV line-up of the group imploded.

Coverdale retreated to pick up the pieces of his career. Bolin tried to do likewise but in December 1976 died from a heroin overdose in a Miami hotel room. That’s a whole other story.

Coverdale recorded some great, gritty stuff with Purple – the highlight being probably the super-sized Mistreated, with its heart-flailing opening line of: ‘I bin mis-treeeaaated!’ But with Blackmore tweaking the strings of the band as well as his Strat, Coverdale was directed to write lyrics with a more mystical bent. The type of style that would truly manifest itself in Blackmore’s Rainbow.

When this writer first met Coverdale in February 1976, on tour with the Mk IV band in Texas, the frustration was beginning to show. Blackmore was no longer in the Purple picture, but Coverdale still found cause for complaint: “I’m very keen to find out what I’m able to do in the studio, on my own. I want to sing rather than scream my balls off. I’ve been fucking screaming for years now, you know…”

He got the chance to prove himself sooner than he might’ve anticipated. “I’ve always had a decent enough scream,” Coverdale reflects, “but, believe it or not, I tried to avoid screaming so much at the beginning of Purple. After Ian Gillan’s trademark style, I thought it inappropriate. But so many of Purple’s songs contained that element, there was no choice, to be honest. Also, having to compete with their insane, but perfect, hard rock volume on stage… I had no choice, I tell you!”

After a pair of low-key Coverdale solo albums – Whitesnake (1977) and Northwinds (1978), both of which featured Micky Moody on guitar – a fully fledged band emerged, and a modest EP called Snakebite was recorded and released in summer 1978. But David Coverdale’s Whitesnake, as they were then billed, looked like a band out of time. Gob-spattered Great Britain was still in the grip of punk rock frenzy. The grizzled, denim-clad dudes in Whitesnake looked passé. And then some.

“Whitesnake were actually formed to promote Northwinds on a one-off promotional tour,” Coverdale clarifies. “I didn’t know whether it would survive. There weren’t many people backing this unfashionable horse.”

“We were the original bearded pirates,” says Bernie Marsden. “Nobody gave us a chance. We were so ignorant of what was going on – well, I certainly was. I remember being in Munich with Paice Ashton Lord, and people were talking about punks. But punks to me were the guys in Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry movies.”

“Whitesnake’s music had such a great feeling to it,” says Micky Moody. “The band were all highly rated musicians and it showed in the performances. Of course, we were into the blues – people like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band of the 60s; we listened to that kind of stuff. We were all heavily influenced by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and their ‘Beano’ album [so called because it featured Eric Clapton reading a copy of The Beano on the cover]. I did like The Yardbirds with Jimmy Page; that almost psychedelic tinge they had. It was exciting.”

“What people don’t necessarily realise,” says Neil Murray, “is that myself, David, Micky and Bernie all came out the formative period of 1966 to 1967, when the blues was really the booming thing in Britain. When I started playing professionally in 1974 I took it more into the jazz-fusion area. But when the opportunity came to join Whitesnake, it just brought out what was latent in my past.”

“As much as I love the blues,” says Coverdale, “it was never a driving ambition for me to start a pure blues band. I’m a big fan of progressive blues by bands like The Allman Brothers. They were quite an influence on how I wanted to structure a group, given the opportunity. Cream, Mountain and, of course, Hendrix were immense in my sphere of influence. The original Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac were huge to me. And then, of course, there are my touchstone inspirational albums, Jeff Beck’s Truth and Beck-Ola. My God, did they connect with me.”

Back to Whitesnake’s Snakebite EP of mid-’78. It contained four perfectly formed songs, kicking off with the straightforward strut of Come On.

“Micky and I were both avid Allman Brothers fans. Still are,” says Marsden, echoing Coverdale’s sentiments. “Lynyrd Skynyrd as well. Anything with that kind of bluesy guitar. There weren’t many people in Britain doing it. But David loved that kind of feeling. I’d throw in some Albert King and Micky would do his bit, and suddenly it all started coming together. We went up to David’s house in Archway [north London] and wrote Come On more or less straight away. I thought how great it was to be writing for a guy with such a great blues voice.”

The Snakebite EP was completed by the honky-tonk barroom boogie of Bloody Mary; Steal Away, with Moody outstanding on slide guitar and Coverdale growling like a hot-blooded houndog; and the aforementioned Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City, which quickly established itself as the highlight of Whitesnake’s live set.

“I had no idea that Ain’t No Love… would be such a popular song. It was a total shocker,” Coverdale reveals. “I had been enjoying Bobby Bland’s work for years. While I was with Purple he released two very contemporary albums in the early 70s, His California Album and Dreamer, which is where the song comes from. Bobby actually does it in a more uptempo, rather dancy fashion. With beautiful singing, of course. Micky and I slowed it down and put a loping riff on it to audition bass players, to be honest. There was never a plan to record it. We just didn’t have enough material to fill the EP.”

But soon enough the famous Whitesnake choir adopted Ain’t No Love… as their own, singing along to the song at every show and rendering Coverdale’s role practically redundant in the process. When Whitesnake headlined the Castle Donington Monsters Of Rock in 1983, the festival’s chorus line was in particularly fine voice.

Mel Galley, who was playing guitar in Whitesnake at the time, recalls: “I’m as blind as a bat, only David would never let me wear glasses on stage. But even I could see how everyone in the crowd was singing when they switched on the floodlights and shone them out front. David and me, we were actually sobbing on stage. It was that emotional. It’s a classic song. David can do such beautiful, bluesy things if he wants to. I’d have given anything to have done a lovely bluesy album with him. But then he made his mark in America with all that glam rock.”

We’re getting ahead of ourselves here. The classic – some might say definitive – Whitesnake line-up began to take shape around the Trouble album, which was released in autumn 1978. Jon Lord was a late arrival during the recording sessions, replacing Pete Solley (who had briefly succeeded Brian Johnston). Upon the release of second album Lovehunter (1979) Ian Paice came on board instead of drummer David Dowle. But was Coverdale actually trying to reassemble Deep Purple? It seemed that way to many observers, who accused him of having a secret gameplan.

“I thought it most amusing that anybody would think me so Machiavellian,” laughs Coverdale. “As if I had such a masterplan to re-form Deep Purple under my own flag. No, that’s just how it happened. There was no big plan at all, and they [Lord and Paice] were most welcome. Only I would have loved for us to have been more commercially successful at that time, as I’m sure they would too.”

Speaking to Modern Keyboard magazine in 1989, Jon Lord reflected: “David talked me into joining. He was calling me for six months and then, in August of ’78, I finally said yes. One reason I agreed was that, by joining Whitesnake, it gave me something to do. I went from playing huge auditoriums with Purple to small clubs with Whitesnake. It was a real shock to the rock’n’roll system, but a very salutary thing for the ego.”

“Paicey and Lordy coming in was the icing on the cake,” adds Coverdale. “They nailed the foundations and we took it from there. But the pressure of coming up with two albums’ worth of original material every year proved too much for me as a singer and as a writer. For all of us, it just got too much. But we certainly jammed a lot of good stuff in those initial three or four years.”

Reminiscing about Whitesnake’s early days, Bernie Marsden says: “It was great. We went on the road with a Mercedes van, with the gear in the back and seats for all of us, in the front and in the middle. Me, David and Micky would usually sit together in the middle row. It was a little family on the road with this huge star of Deep Purple. But David was just an ordinary bloke to me.”

Micky Moody agrees: “Yes, we were just blokes. David wanted to be back with the lads and he was very happy about it.”

Once Lord and Paice had established themselves in Whitesnake, Marsden decided to start wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the legend: ‘No, I wasn’t in Deep fucking Purple.’ Were the cracks beginning to show already?

“No, not at all,” Marsden says. “It was just that when we used to do interviews together, all the journalists wanted to talk about was Purple. So when they asked a question I’d just point to my T-shirt and say: ‘Look a little closer.’ Because Deep Purple was in big letters and the remaining words were in small letters that you could hardly see.”

They might’ve been swimming against the punk rock tide – with Coverdale inevitably doing the breast stroke – but Whitesnake grew in stature steadily. Trouble reached No.50 in the chart and Lovehunter cracked the Top 30. One of the outstanding tracks on the latter is the dramatic and progressive Walking In The Shadow Of The Blues, one of Coverdale and Marsden’s greatest compositions.

“That song really summed up my musical approach of the time,” Coverdale says. “It was very much my feeling, my perspective and probably my life’s philosophy back then. The lyric more or less wrote itself. It was very free-flowing, very autobiographical. It was just waiting to be written. Bernie and I put the music together very quickly. It was obviously meant to be as a song. I’m very proud of that one.”

“Those were fun times,” says Marsden. “Ask Jon Lord about it – he never stopped laughing for two years. The best and funniest time he ever had in his career was in Whitesnake. We did have a laugh, but one of the main instigators of these laughs was David Coverdale. He was a clever wind-up merchant. I’ve got pictures of us playing football in Spain, and they’re not pretty. David’s playing centre forward with his hair all greasy and his shirt off. Micky Moody is in goal wearing a pair of big boots. I have the photos. And this is from a guy [Coverdale] who later said me and Micky didn’t take our careers in Whitesnake seriously enough.”

Ian Paice also had the time of his life in Whitesnake, although he’s not so convinced about Coverdale’s sense of humour: “The funniest band I’ve ever been a member of was Whitesnake. David’s not a funny guy but Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden were a constant source of laughter. Touring was so much fun, I can’t remember the bad times even though I know there were some. Neil Murray is a straight guy and these two used to take him to bits all the time. They used to do it to Coverdale as well, take the piss out of him.”

The ’Snake albums kept on uncoiling at a remarkable rate. Ready An’ Willing (1980) reached No.6 in the chart and Live… In The Heart Of The City (also 1980) climbed to a position higher. These were heady, boozy, bluesy times, and they reached their climax when 1981’s Come An’ Get It got to No.2. It was only kept off the top spot by Phil Collins’s mawkish Face Value.

“Come An’ Get It is my favourite of the early Whitesnake albums,” says Coverdale. “It’s down to the band’s performance and the consistency of the songs. Production’s good from Birchy [Martin Birch] too.”

Neil Murray concurs: “Come An’ Get It is a great album. It’s the zenith of the ‘classic’ line-up. Ready An’ Willing is very good, the live album is pretty good, but overall Come An’ Get It takes the biscuit. Who knows? Ask the fans, really. Don’t ask me. I was perfectly happy with the way things changed later on as well. The 1987 album [which Murray played on, although he wasn’t part of the touring band] was great too. I’m very much on the fence when people say Whitesnake were crap after Saints An’ Sinners [the 1982 follow-up to Come An’ Get It], or when they say they hate all the old blues stuff. I can enjoy a lot of it, right across the board.”

Sadly, the demise of the Coverdale-Moody- Marsden-Lord-Murray-Paice line-up was approaching.

Coverdale: “The vibe in the band had noticeably changed. The energy was low at rehearsals and it was evident that enthusiasm was on the wane. The suggestion of adjourning to the pub was greeted with more eagerness than working on the new tunes. It seemed to me that some of us were content just to cruise on our ‘gold’ status… and I was hungry to go further.”

Moody: “More interested in going to the pub than the studio? Well, yeah. Personally I think I was at the time. That was my way of saying: ‘I’m bored now. I’ve had enough of this.’”

“Everything was fine up to Saints An’ Sinners,” Marsden remembers. “But at some point or other David decided he would be king of Whitesnake.”

Management shenanigans with John Coletta, an old nemesis from Deep Purple days, plus the distraction of solo albums from the likes of Lord and Marsden, played their part. Coverdale’s marriage to his then-wife Julia was in trouble, and their daughter, Jessica, suddenly contracted bacterial meningitis. All of which contributed to the singer’s decision to place Whitesnake, as he put it, “on a holding pattern over Heathrow”.

By contrast, Marsden claims that he, Ian Paice and Neil Murray walked out on Whitesnake after a make-or-break meeting with management that Coverdale failed to attend.

“David is very good at remembering only the bits he wants to in interviews,” claims Marsden.

“Coverdale had become a bit detached from everybody,” confirms Moody.

Murray: “It may well have been that David wanted a complete change. At the end of the Saints An’ Sinners recordings, there came a time when he [Coverdale] was splitting from not only the management, but also from the publishing and record companies. It was quite a major thing to do. He had to buy himself out. So he may well have said: ‘Okay, I’m going to start completely afresh with a new band, we’ll see what happens after that.’ Who knows? The difficulty is that David will say something to the press and, even though it’s not quite what actually happened, he’ll say it so many times that he comes to believe it himself – and therefore everyone else does, too.”

The blues-rock era of the band was coming to an end, but the ’Snake slithered on. In October 1982 a brand new line-up emerged to promote Saints An’ Sinners, which had had a long and painful gestation. Lord and Moody were still there alongside Coverdale, and the band was completed by guitarist Mel Galley (ex-Trapeze), bass player Colin Hodgkinson (ex-Backdoor) and drummer Cozy Powell (ex- just about everyone). It was this version of Whitesnake that headlined the 1983 Monsters Of Rock, complete with swooping helicopters and blazing searchlights during Powell’s drum solo.

But all the showmanship was becoming too much for Micky Moody: “David had become the star. He wanted to put together more of a spectacle than a show. You had to have an appointment to go and see him. I resented that. This guy used to help carry my gear a few years ago.” Eventually ex- Tygers Of Pan Tang guitarist John Sykes replaced Moody. A little later, Neil Murray was welcomed back into the fold.

Moody: “What David didn’t – and still doesn’t – realise is that I never wanted to be a great big star. I was always a muso. I found it difficult to be a rock star, I really did.”

Explaining his intentions at the time, Coverdale says: “I wanted the blues element in the band’s identity to ‘rock’ more. John and Cozy put a welcome firecracker up my arse after all the jolliness, merry-making and the safe approach. And that’s why they were there. To electrify Whitesnake and help me take it to the next level. And that’s what happened.”

But Whitesnake’s next album, Slide It In, emerged in February 1984, certain sections of the music press were baying for Coverdale’s blood. Most of the tracks had been co-written by Coverdale and Galley at the former’s house in Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire. But in-between still-brilliant songs such as Love Ain’t No Stranger Coverdale’s boisterous machismo had reached fever pitch. Spit It Out, for example, contained the chorus: ‘Spit it out, spit it out, spit it out/If you don’t like it/Spit it out, spit it out, spit it out/If you don’t like it.’ About as subtle as a sledgehammer.

Sounds journalist Garry Bushell gave a hammering. The headline to his review was ‘Chop It Off’. “The Coverdale I recall was a vain, preposterous oaf,”

Coverdale remembers Bushell’s review vividly. “It was most unfortunate and unnecessary. But who cares? It [Slide It In] sold over four million in the States alone. Probably more, by now. It’s his [Bushell’s] karma. In any case, the blues has always had a strong macho streak. Listen to Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters… I have some very early recordings that make my stuff sound like nursery rhymes.”

Whitesnake had never managed to crack the American market. But since Saints An’ Sinners they had acquired a powerful new label over there, Geffen. They also had a fierce supporter of their cause in John Kalodner, Geffen’s legendary A&R man. Kalodner was determined for Whitesnake to succeed in the States and his ruthless approach rubbed off on Coverdale.

Moody: “Kalodner turned up at some German dates. I looked around mid-performance and there he was – this rather sinister character – making notes by the side of the stage. That didn’t make me feel too secure. I thought: ‘Sod this, I’m off.’ I was being treated as a session player.”

When Mel Galley injured his arm in Ludwigshafen, Germany, he soon found himself out of Whitesnake. “We’d been to a funfair and we’d played some 10-pin bowling,” says Galley. “Me and John [Sykes] came out and did the old prank of running over cars. There were two Mercs and I fell off the boot of the second one, and then John landed on my arm.”

Galley contracted a virus while in hospital that ate away the nerves from his hand right up to the base of his skull. To enable him to play guitar, his hand was encased in a metal contraption that resembled a toast rack.

“I’ve still got it. I call it The Claw. I still have to wear it. The nerves that control the muscles don’t work so it acts like a mechanical muscle.”

“[Coverdale] said, ‘I don’t want to see you in the band with that on your hand’,” Galley says diplomatically. “But I have no regrets. You have to be philosophical. The Kalodner period was taking over and Whitesnake were turning into an MTV band. Obviously I smashed my arm but I’m not going to say anything bad about him, because it’s David and it’s something we went through.”

With Jon Lord leaving to join the re-formed Deep Purple Mk II, the stage was set for Whitesnake’s transformation into the multi-platinum, tight-trousered, Tawny Kitaen’d combo that most people remember today. But ironically, the glossy new Whitesnake relied heavily on two songs recycled from the old days to launch their career: Here I Go Again (originally on Saints An’ Sinners, written by Coverdale/Marsden) and Fool For Your Loving (on Ready An’ Willing, by Coverdale/ Marsden/Moody).

Marsden: “John Kalodner had heard Here I Go Again and he said to David: ‘It’s a No.1 record.’ He was right. Even now, Here I Go Again grows another arm every year. It’s a massive, massive song. The royalty cheques are very welcome. David said I should thank him for that.”

Moody: “There’s no emotion on the new version of Fool For Your Loving. The original with Bernie’s great guitar solo is far superior.”

These days Marsden, Moody and Murray are intent on keeping the spirit of early Whitesnake alive in M3, their band that specialises in playing classic ’Snake songs. “There’s legions of people in America who don’t know me and Micky Moody were ever in Whitesnake,” Marsden says. “But they certainly know our tunes. Equally, there’s legions of people in Europe who wish they could see Coverdale-Marsden-Moody on stage again.”

“It’s funny,” muses Murray, “because me and Bernie would quite often enjoy listening to soft American rock on the road, and David would pooh-pooh it and say: ‘What’s this rubbish?’ But then three or four years later he’s deeply into that style. I’m not saying that when he did it, it wasn’t genuine. We all change. But to me, the modern Whitesnake play the old stuff in a very heavy-handed, rather bludgeoning way.”

Coverdale reflects: “The early days were without question totally necessary. Everything needs a beginning, a foundation in order to grow. I couldn’t have asked for a better way to start the ball rolling, or better players and people to be involved with. I’ve recently seen some of the things I’ve said [about the old band] over the years and I regret most of them. It wasn’t necessary.”

However, he offers the proviso: “On the other hand, it doesn’t disturb me that some people are unaware of how long Whitesnake has been kicking around. I have never had a problem slipping from one bed to another. Besides, it’s still me singing and writing what I feel, what I want to share. Sometimes I just felt it necessary to redecorate the House Of ’Snake. No disrespect to my former colleagues. Just my need for change.”

Moody responds: “That sounds like a cop-out to me. Whitesnake is an an old band. C’mon – it was formed in 1978. That’s getting on for 30 years ago. Knowing David, I would think he’s not particularly happy about being a grandad in his mid-50s. He doesn’t like people to know that Whitesnake have been going for so long. Mick Jagger would never make a comment like that about The Rolling Stones, that’s for sure.”

Indeed. Whatever David Coverdale might say, the blues still casts a tall shadow over the history of Whitesnake.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 95. Note: since this first appeared, Bernie Marsden, Mel Galley and Jon Lord have sadly passed away.