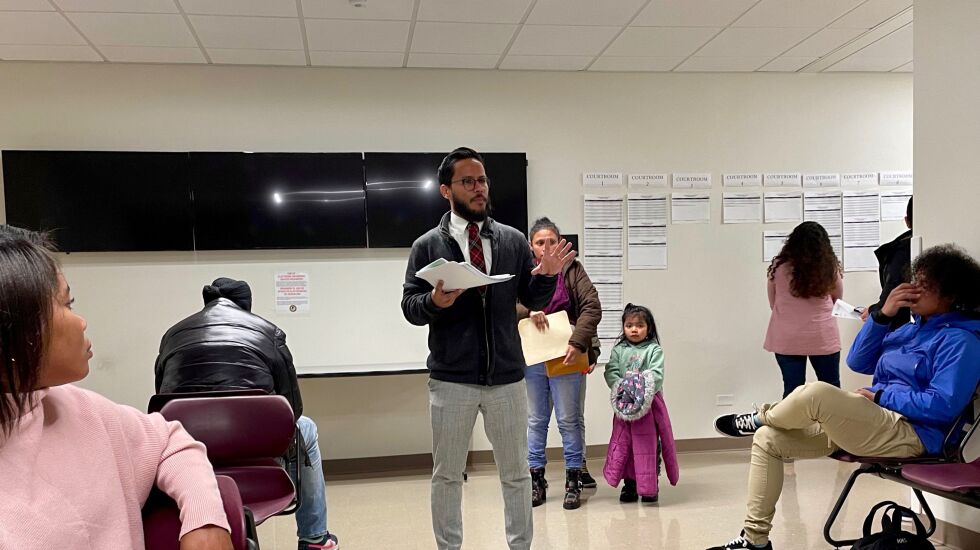

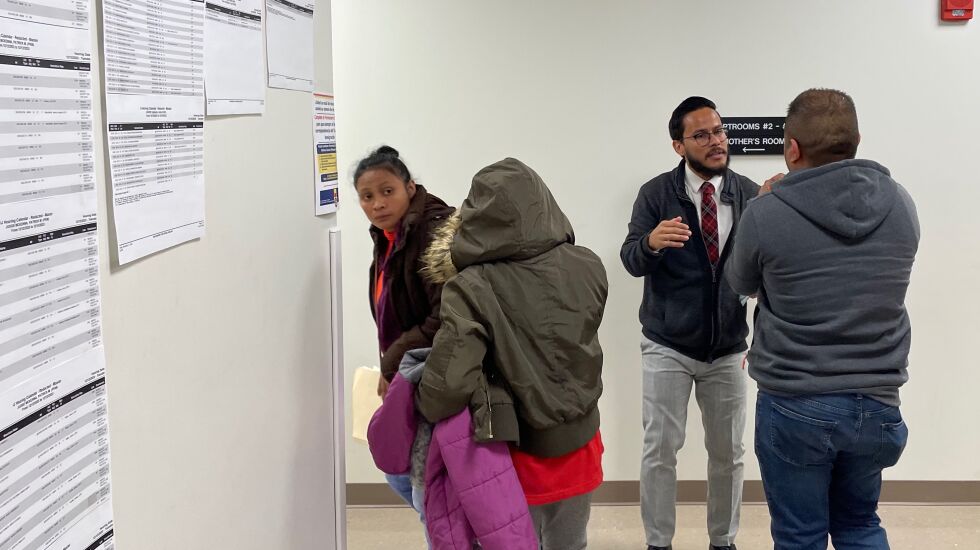

“Hola, como esta?” says JuanCamilo Parrado, shortly after 8:30 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, standing before about 30 people — mostly couples, a few parents with young children — in a spartan government waiting room outside immigration court on the 15th floor of 55 E. Monroe. “Español? Si?”

Having said hello, asked how everybody is doing — struggling to navigate a labyrinthine legal system in a new country in a language most only barely comprehend, thank you very much — and whether they speak Spanish, Parrado, a managing attorney at the National Immigrant Justice Center, uses that language to get down to business: informing them of their rights, as immigrants. To a hearing, to a lawyer at no expense to themselves, the chance to cross examination witnesses. To file an appeal.

Though those rights have a way of colliding with reality.

Around the corner, for instance, in Judge Gina Reynolds’ courtroom, immigrant Aslan Usmanov is waiting for the 9 a.m. hearing that he has a right to. But another right — to an interpreter — is proving difficult to fulfill.

“What language are you holding for?” a disembodied voice asks from some kind of dial-in translation service.

“Russian,” Reynolds says.

“At this moment, we don’t have a Russian interpreter available,” the voice replies.

The court system claims it is prepared to handle some 300 languages, with “in-person, video remote (Webex) and telephonic interpretation services,” though some languages are translated more readily than others.

“They’re pretty good about it, though when it comes to finding the right dialect, it can be a real challenge,” said Mark L. Adkison, a lawyer with Adkison Law Offices, a family firm exclusively handling immigration work. “Creole and Yoruba can be tricky.”

Reynolds shifts to the Spanish speakers in the courtroom — a pair of Venezuelan immigrants — and hears their cases while the Russian interpreter is tracked down. The judge is methodical, calm and painstaking.

“If anyone has trouble with the earphones, let us know right away because everyone should understand everything being said,” Reynolds explains.

Of course, hearing words in a language you comprehend is not the same as grasping America’s complex immigration legal system. As Chicago tries to digest its staggering spike in immigrants, the bulk of attention has gone to the difficulties of housing 25,000 or so Venezuelan refugees, most shipped here from Texas over the past year, in a cruel but effective political stunt by Gov. Greg Abbott.

But housing — and food and warm clothing — are only the start. Immigrants’ journeys will have been in vain, and might end in deportation, if they can’t also thread the legal needle, an area where the weight of their numbers is putting serious cracks in the bridge to the American dream.

“We’re seeing the immigration system buckle, just a system that’s overwhelmed,” said Lisa Koop, director of legal services at the National Immigrant Justice Center in Chicago. “We’re getting clients who are not scheduled for court until 2026. The city of Chicago, the state of Illinois has really innovated and worked hard trying to welcome people and honor their dignity. But without a broader federal plan it is really tough sledding.”

Remember: The system was broken before the latest mass arrival.

“What we’re facing now is an influx of immigrants snowballing over an already-choked system,” said Wade A. Thomson, a partner at Jenner & Block, leading the firm’s pro bono immigration efforts. “It’s never been harder to represent anyone in the immigration system. The judges are overworked. The rules have not caught up.”

Just showing up at the right courtroom in the right building in the right city at the designated hour is one of the larger hurdles, particularly when you consider an immigrant carrying all his possessions in a pillowcase can cross the border into Texas, be given a piece of paper assigning him to a hearing a year later in Phoenix, then be put on a bus going to Chicago, where they know no one.

“Immigrants received at the border are ordered to report to immigration hearings around the country,” said Kimball Anderson, a partner at Winston & Strawn, who has been spearheading that firm’s immigrant efforts. “They have been released on their own recognizance but may have a paper from Homeland Security ordering them to appear at an initial immigration hearing in Denver or Nashville or Dallas or Indianapolis.”

An ad hoc legal framework has arisen to try to help new arrivals, but that’s rather like trying to assemble a plane as it taxies down the runway.

“We’re still in the pilot stage, trying to figure out how to do this fast,” Koop said. “What we’ve learned is, there aren’t really shortcuts. It’s a long and complicated process, with no consistency. How people are being processed at the border depends on where and when they entered. Two people who seem in similar situations can have very different paperwork. It goes a lot faster if you have an immigration attorney.”

Getting the attorney can be the easy part. After speaking for 20 minutes, Parrado, who manages the NIJC’s immigration court helpdesk, invites anyone who wants legal guidance to meet with him, one at a time. A Nigerian immigrant waiting with his wife and child on the 15th floor (he did not want his name used — many are worried about somehow negatively affecting their cases by talking with the press) already has an attorney, through the recommendations of friends.

Waylaying passersby is another technique. Winston & Strawn’s Anderson isn’t an immigration lawyer — he’s a commercial litigation trial attorney — and doesn’t speak Spanish.

But he wore a necktie when he went to the 18th District police station at Larrabee and Division to bail out a pro bono client. He saw the Venezuelan encampments. “The immigrants were impossible to miss.” And they saw him.

“I was wearing a tie and looked like a lawyer and quite a few approached me asking for help. I didn’t go there intending to get involved with this crisis,” Anderson said. “But that’s how it started.”

Since then, he has been gratified by the reaction of attorneys at Winston.

“We’re not in a position as a firm to provide housing, but there was something we could do,” he said. “They have a lot of needs, and we’ve been trying to help many of them.”

“Finding enough attorneys has not been the huge problem,” Thomson said. “Getting them organized and introducing them to the people in need — it’s just a logistical nightmare.”

This might be a moment to mention just how notorious our country is for its topsy-turvy immigration laws. A United States citizen can sponsor the immigration of unlimited numbers of family members, while the national quota of “persons of extraordinary ability” is set at 40,040 a year nationwide.

“If you are a professional, Canada has an open immigration policy, where the U.S. has a quota-based immigration policy,” said Pashant Ajermera, an immigration attorney in Ahmedabad in western India, who recommends highly skilled workers choose Toronto over Chicago.

“I can immigrate to Canada if I have a master’s degree and am fluent in English, register and have a green card within a year and a half. Whereas in the United States and its quota-based immigration system, you can study in the U.S. and be an IT professional, and there are 465,000 IT professionals waiting for a green card ahead of you. The waiting time is 125 years.”

That’s both a staggering figure and perhaps conservative. Five years ago, the Cato Institute estimated the wait at 150 years.

The legal community in Chicago can’t change the laws, directly, but is still trying to do what it can to address the immediate problem.

“It’s certainly been a call to arms at Jenner,” Thomson said. “Not just the lawyers — we’ve got secretaries, paralegals, all sorts of people answering the bell.”

The mobilization is across the city.

“I’m very proud of the legal profession in Chicago,” Thomson continued. “A lot of us know how close we are — our own ancestors, longing for better lives. ... Many organizations, humanitarian groups, regular Chicagoans have stepped up, and I’m super proud of it.”

Available legal representation not only facilitates the integration of immigrants into Chicago but also draws them to the city. I sat down with a 25-year-old Venezuelan named Arbert, who came to Miami a year ago, lived there for five months then decided to come to Chicago in March.

Why change cities?

“I could be legal here,” he said, in Spanish. “The immigration process would go quicker. There was no legal help in Miami.”

And how has the process been going?

“Very good,” said Arbert, who did not want his last name used or his face shown, for fear of reprisals should he be forced to return to Venezuela. “Things are great so far. It’s a little bit complicated, and if I were doing it myself, it would take longer. But when I got here I was able to connect.”

His shelter put him in touch with the National Immigrant Justice Center.

“Now that I have attorneys, the process is a lot better,” he said. “Things are going pretty great now.”

I asked Arbert what he expected to get out of coming to America, and he gave an answer that could have been given by any immigrant from any country in 1923 or 1883, or any time in the city’s past, or, I imagine, at any point in the city’s future.

“A better life for myself, a better life for my kids,” he said. “Truly, just stability and better opportunities for my life.”