Australia has never been more awash in cash, not that you'd know it.

Around $100 billion of banknotes are in circulation, latest estimates from the Reserve Bank of Australia show - including a massive $19 billion surge during the pandemic.

But, at the same time, cash is disappearing from our daily lives - so much so the armoured car business appears to be in near-terminal decline, and ATMs might not be far behind.

Tap and go and other digital payment options have rapidly supplanted banknotes as the preferred method of payment.

From being used in 70 per cent of all transactions in 2007, cash was involved in just 13 per cent in 2022.

So, if it is not being used to pay for things, where is all that cash? And what is it doing?

Not very much, is the short answer, RBA researchers say.

They reckon between $56 billion and $81 billion is currently stashed in suitcases, buried in backyards, stuffed under beds, on ice in freezers and stored anywhere else people can hide it.

The tell is in the composition of the notes left out there.

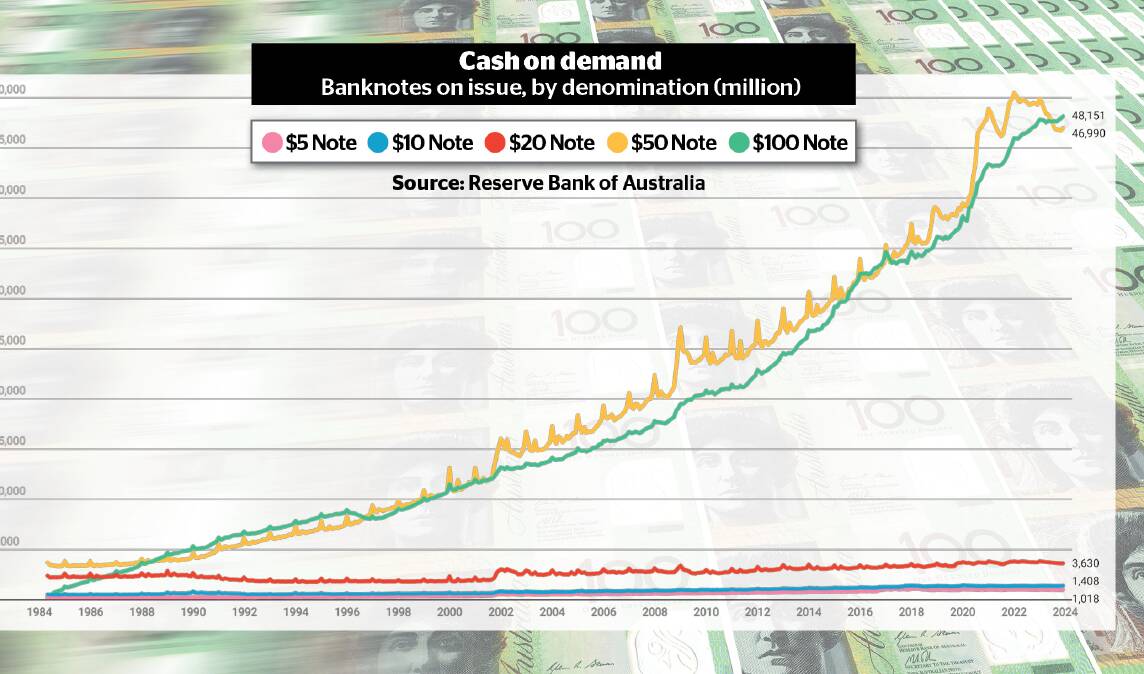

Since the global financial crisis the number of $50s and $100s in circulation has climbed significantly, particularly during and after the pandemic.

There are now almost 40 $50 notes for every man, woman and child in the country (up from less than 20 in 2007) and nearly 20 $100 notes (from less than 10 over the same period).

These are the banknotes the central bank reckons people are choosing to hoard.

Meanwhile, demand for the small denomination notes used in everyday transactions - $5, $10 and $20 notes - has stagnated over the past 15 years.

Less brass in pocket

For Tighes Hill grocer, An Apple A Day, the changing habits and the associated merchant fees are just one piece of the puzzle that make it difficult for small businesses.

Many businesses in Australia add a small surcharge at the till to cover the transaction fee set by their bank or financial provider for card payments.

Owner Shereen Morris said they don't have customer surcharges but they do consider merchant fees when pricing products.

"We have to take into account that we are going to lose one to one and half per cent of everything in merchant fees," Ms Morris said.

She has noticed that customers rarely pay with cash and that probably only three per cent of their transactions are cash.

"People don't really carry cash anymore, it's inconvenient to go and withdraw and it's easier to keep track of finances electronically," she said.

Ms Morris said as an independent grocer the general cost of business, including merchant fees, made it harder to attract and sustain customers.

Business Hunter spokesperson, Sheena Martin, said the cost of doing business was the greatest concern facing businesses across the region.

"Insurance, fees and taxes, and energy costs are chief concerns for business. With cash-strapped customers spending less and the cost of doing business on the rise, businesses have little choice but to pass these costs on to consumers," she said.

Australian Banking Association chief executive Anna Bligh said the trend away from cash was turbocharged by the pandemic, when business closures and movement restrictions forced millions to take their purchasing and financial transactions online.

Australians have embraced digital transactions like few others.

The average number of cashless payments made per person in Australia reached almost 500 in 2021, ahead of the United States, Britain, Germany and France, the ABA said.

Since 2018, the share of retail sales conducted online has doubled, from 5 to 10 per cent. In banking, almost 99 per cent of transactions are now conducted online and the number and use of ATMs has plunged.

Withdrawals from ATMs have fallen from almost $160 billion in 2009 to less than $110 billion last year, and the number of machines has tumbled from almost 33,000 in 2016 to around 25,000 in 2023.

The shift away from cash has made moving money around and paying for things much easier and cheaper.

The days of spending most of the lunch break queuing up at the bank branch or Medicare office are gone for most.

The shift to digital has also helped businesses cut down heavily on costs, allowing them to shut branches, cut back on services staff and virtually eliminate overheads involved in handling cash.

The need for cold, hard cash

But the move has not come without cost, particularly for those for whom cash has traditionally been king, including those in the informal economy, tax-dodgers, people unable to access digital banking or payments systems and even criminals.

From buskers and window washers to employees still paid in notes and coins, cash remains, as Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock acknowledged late last year, "an important means of payments for some people".

Cash can also be important for communities hit by floods, storms and other natural disasters that take out the internet.

In addition, there are those who, for a multiplicity of reasons, are unable or unwilling to engage in digital banking and transactions.

This includes people living in areas with poor connectivity and facing challenges of literacy or technological capability.

Among them is homeless man Danny Masters, who regularly sits in Canberra's city centre seeking cash contributions from passers-by.

As cards have replaced cash in people's wallets and many increasingly use their mobiles to make transactions, people like Mr Masters, without the means to take digital payments, find themselves being pushed further to the financial fringe.

But, as Reserve Bank research shows, demand for cash as a way to store wealth is high - even if, in a high inflation environment, the value of that money is eroding at an accelerated rate.

For all these reasons, the government and the RBA place a high priority on ongoing access to cash.

"While consumers' preference for everyday payments is trending towards digital, it is important that the payments system continues to include, and be accessible to, all Australians," the government says in its strategic plan for the payment system, released last year.

No cashless future

The plunge in the use of cash in the past 15 years has pushed the armoured car business to the brink.

Australia's largest operator, Armaguard, warned last year there was no longer the demand to support the industry as it was then structured, and won regulator approval for a merger with its competitor, Prosegur.

At the time, Linfox Armaguard Group chief executive Mick Cronin said the merger, set to be completed by mid-year, opened the path for a sustainable future for the sector.

While electronic payments were increasingly prevalent, the future would not be cashless. Cash, Mr Cronin said, would continue to have a use, albeit at lower volumes. The Armaguard boss said last year's Optus outage was a reminder no system was infallible.

He said during the breakdown there was a "significant spike" in the use of ATMs as people rushed to withdraw cash to pay for goods and services. "While digital methods of payment will continue to dominate in the future, cash will continue to remain as a secure method of payment that is less exposed to system failures," Mr Cronin said.

Ms Bullock warned in December the economics of the cash distribution system were under pressure. She said despite the Armaguard-Prosegur merger, signs were the armoured car business remained unsustainable.

The RBA has convened talks involving the operator, customers including the banks and retailers and regulators to "discuss what more could be done to promote the sustainability of the cash distribution system", Ms Bullock said.

It is unclear yet what the long-term solution will be. The ABC reported this month the banking sector was expected to step in to save Armaguard's struggling operations, with a proposal for an emergency intervention to be finalised by the end of March.

Cash may never die, and it is clear currently millions feel safer storing wads of notes at home rather than lodging them at a bank. But it has largely disappeared from daily life for most, and there is no reason to think that will ever change.