“Good Samaritan” is a label often used to describe someone acting selflessly to benefit others, even if a total stranger.

Some may recognize that the phrase has its origin in a biblical story, one of Jesus’ parables recounted in the Book of Luke, Chapter 10. In this story, a traveler from the Samaritan community, a Middle Eastern ethnic and religious group, happens upon a man who had been robbed and beaten by the side of the road.

The injured man was ignored by two men passing by, both of whom belonged to groups who were religiously respected in Jesus’ Jewish community: a priest and a Levite, a tribe with special religious responsibilities. In contrast, the Samaritan gives first aid to the victim, places him upon his donkey, and transports him to an inn where the beaten man is housed, cared for and fed – with all his expenses paid by the Samaritan traveler.

As a professor of biblical studies who has written about Samaritans, I’ve learned that while most of my students have heard of the “good Samaritan,” fewer are aware of the social and historical realities reflected in the story – much less that the Samaritan community still exists today.

Hidden lesson

Samaritanism and Judaism share a common origin in ancient Israel, but the rift between the two communities had already been growing for centuries before Jesus’ birth.

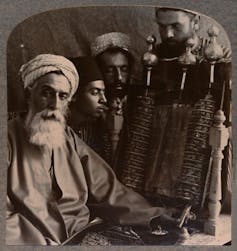

The group’s sacred text is its own version of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible: what Christians know as the Pentateuch, and Jews call the Torah. The Samaritan center of worship is on Mount Gerizim in the present-day West Bank, instead of Jerusalem, where the Jewish temple stood. The faith has its own priesthood, religious calendar and theology. According to Samaritan belief, a messianic figure called the Taheb will usher in an era of Divine Favor, during which the ark of the covenant will be revealed, and Mount Gerizim will be restored as the only recognized center for worship.

Throughout the group’s history – particularly during the first century, the backdrop for the story in the Book of Luke – the Samaritans have often been marginalized and discriminated against by their neighbors. The relationship between ancient Jews and their Samaritan neighbors was hostile, so people listening to the story would have been shocked that the hero was a Samaritan.

Effectively, the parable turns social reality on its head. Those expected to act righteously and model behavior for others to imitate failed where the Samaritan succeeded. The parable challenged social norms and prejudice based simply on ethnic origin, religious affiliation and where people made their home.

Biblical mentions

The story of the Good Samaritan is not the only time the Samaritan community makes its presence felt in the New Testament literature.

Just one chapter earlier, Luke 9, describes an unwelcome reception Jesus’ disciples receive as they are about to enter a Samaritan village. Jesus and his party are making their way to Jerusalem: an offense to the Samaritans’ belief that Mount Gerizim is the proper place for worship, an issue that often functioned as shorthand for all that separated the two communities.

The villagers therefore choose not to help the travelers on their way. In response, the disciples are ready to call down divine retribution as punishment from heaven. Jesus will have none of it, and rebukes the disciples while leaving the villagers in peace.

The Gospel of John depicts an especially significant conversation between Jesus and a Samaritan. Worn out by a recent journey, he asks a woman to draw water for him at a well. She is rather taken aback, for as the editor of the the chapter explains, Jews don’t mingle with Samaritans. Nevertheless, she does as he requests. Their ensuing conversation mentions major tenets of belief where Samaritanism and Judaism differ, despite their many similarities: their contrasting ideas about prophets, “Messiahs” and where to worship. According to the story, she and many people from the nearby vicinity become followers of Jesus.

Early converts

In fact, it is quite likely the Samaritans were among the first followers of Jesus’ movement.

In the Book of Matthew, Jesus directs his disciples to preach only to the house of Israel, and not to Samaritans or non-Jews, seeming to display an anti-Samaritan bias. The Gospel of John paints quite a different picture, however, first with the account of the Samaritan women at the well.

Later in John, when detractors accuse Jesus of having a demon and being a Samaritan, he only denies the first – seemingly refusing to distance himself from the Samaritans.

The Book of Acts, which describes the start of the Christian church, includes the story of Stephen, who is described as the first martyr among Jesus’ followers. Acts 7 depicts Stephen trying to defend himself against charges of blasphemy, using a text that is at least influenced by Samaritan tradition, if not a version of what will become the Samaritan Pentateuch itself.

The Book of Hebrews in the New Testament also shows Samaritan tendencies, such as referencing heroes from Samaritan tradition.

Despite this important role in the beginning of the Jesus movement, the relationship between Christianity and Samaritanism has not always been positive. The group has often been required to navigate between much larger and more powerful groups, whether they be Jewish, Christian or Muslim. Violence, displacement and conversions – both voluntary and forced – have dramatically diminished the Samaritan community over the centuries.

21st century Samaritans

Today, the Samaritans number somewhere around 1,000 people. Most are in communities outside Tel Aviv and near the West Bank city of Nablus, where they find themselves situated between Israeli and Palestinian cultures and institutions. Most Samaritans hold Israeli citizenship and have Israeli health insurance, but many also attend Palestinian schools, speak Arabic and have both Hebrew and Arabic names.

The small size of the modern Samaritan community makes them easy to overlook. But for those who are willing to listen, the message of the Good Samaritan – a message of kindness, not blinded by nationalistic, religious or ethnic prejudice – resonates as loudly as it ever has.

Terry Giles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.