Microsoft recently announced a new partnership with InWorld AI to create a suite of what it calls “AI game dialogue and narrative tools.” Predictably, many of the humans currently responsible for bringing that dialogue to life aren’t thrilled.

In its announcement, Microsoft lays out two specific tools its partnership will develop:

“An AI design copilot that assists and empowers game designers to explore more creative ideas, turning prompts into detailed scripts, dialogue trees, quests and more.”

“An AI character runtime engine that can be integrated into the game client, enabling entirely new narratives with dynamically-generated stories, quests, and dialogue for players to experience.”

Microsoft insists its tools are made to empower developers, linking to its own AI policies that include safeguards against using AI voices to impersonate real people and acknowledging the racial biases that can be built into AI. However, for the voice actors whose work the partnership could outsource to AI, issues with the technology run much deeper.

“I believe generative AI is inherently harmful by nature — especially when unregulated,” voice actor Abbey Veffer tells Inverse. “The whole intended purpose of AI is to replace manual, human-powered creation.”

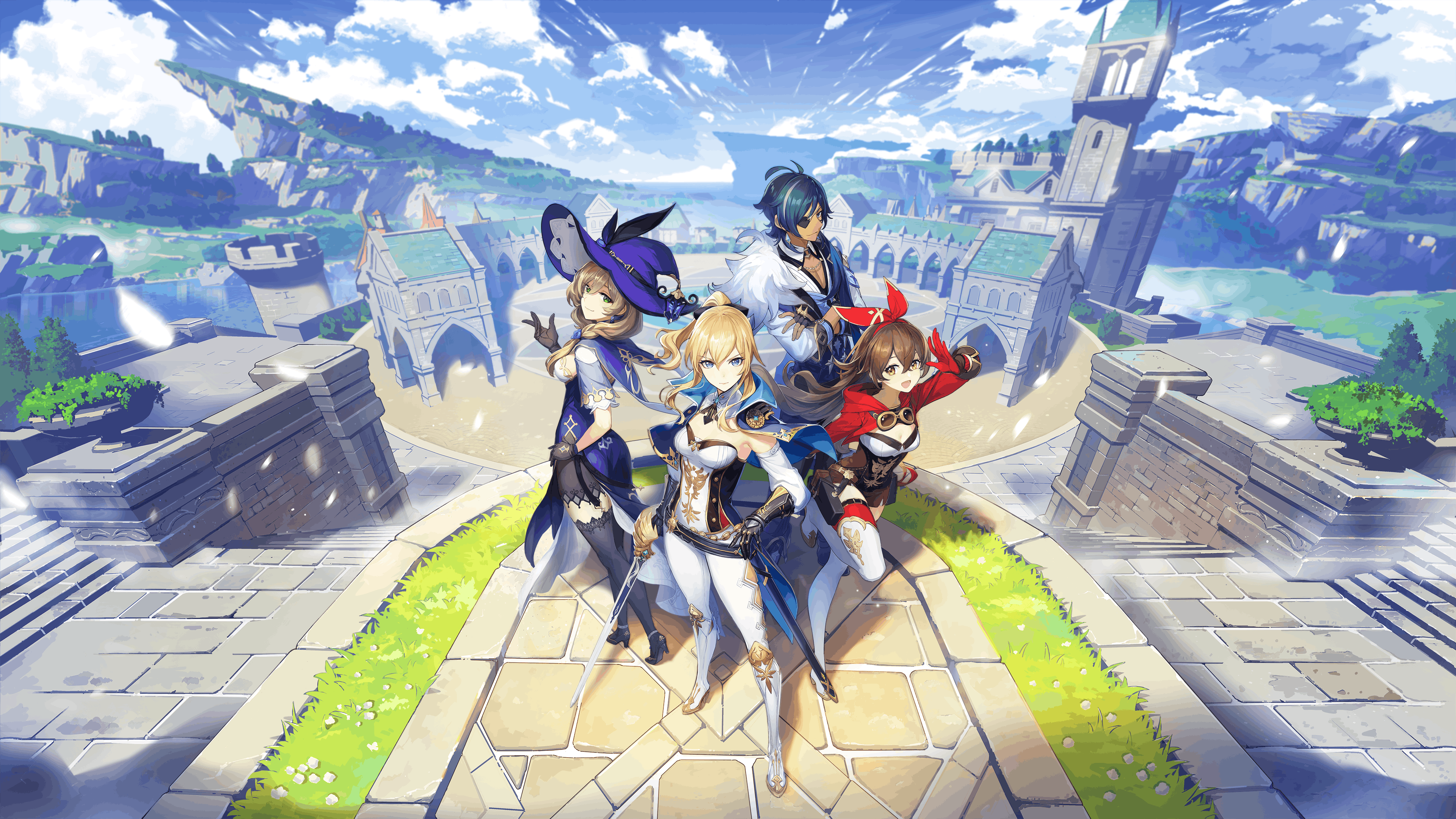

For people like Veffer, whose credits include Genshin Impact and The Elder Scrolls Online, it’s not necessarily how AI is used that’s the problem, it’s who AI will replace. InWorld is already working on AI-powered NPCs that respond to players with automatically generated dialogue spoken in a synthetic voice.

A video on the company’s website shows its AI NPCs warning players about nearby threats in a game and even answering direct questions. InWorld describes the video as positing “a world where NPCs are more than just side characters,” but for the actors who voice said NPCs, they’re already more than that.

“Real people are the reason audiences and players fall in love with fictional characters,” voice actor Shelby Young, who portrays Princess Leia in Lego Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga, tells Inverse. “All of us have our own quirks, funny ways we may say or interpret a line of dialogue that a machine wouldn’t be programmed to do. We see parts of ourselves in these characters.”

InWorld’s own announcement cites a survey it commissioned, which found most players wanted “more engaging and dynamic NPCs” in their games. The company says its technology could deliver that. Especially in massive open-world games, there can be thousands of NPCs with unique dialogue and voice lines, from quest-givers to random passersby. It’s easy to see why a cost-conscious developer might want to automate the creative work involved in that. Still, NPCs occupy an important part of the professional landscape for voice actors.

“The NPC area is where a lot of working-class, blue-collar voice actors get their start and do a bulk of their work,” Tim Friedlander, president of the National Association of Voice Actors, tells Inverse. “Replacing these actors with synthetic voices that are not ethically sourced will destroy a large part of the video game voice acting industry and affect a large portion of middle-class voice actors who will lose their livelihood.”

The ethical sourcing of AI voices is a major focus of NAVA’s fAIr Voices campaign, which proposes that actors should always have to give consent for their voices to be used in AI projects, that those synthetic voices should be used only for purposes actors agree to, and that actors should be compensated every time it’s used.

With no such standard currently in place at a large scale, some actors have seen recordings of their voices used to train AI models without their knowledge and with no compensation, according to Friedlander.

Veffer says they once had a client start using AI voices after they began working together and signed a contract allowing use of their voice without realizing it.

“It was before I knew that it's essential to comb through contracts to ensure there aren't any clauses pertaining to ‘usage in perpetuity’ and other ‘red flag’ language to look out for,” Veffer says. “In my naivety, I signed away my rights.”

It’s not clear yet what protections Microsoft’s collaboration with InWorld may offer to voice actors and other workers impacted by the use of AI, and neither company responded to a request for comment.

“As much as I'd like to see it done away with entirely, I don't know if we can completely eradicate generative AI usage,” Veffer says. “I think an optimal scenario we can hope for is legislation and contracts in effect to enforce boundaries, ensure protection from malicious misuse, and guarantee compensation for agreed-upon terms.”

For actors like Veffer and Young, the use of AI at all is a threat to both their careers and their craft.

“We need humanity in art,” Young says. “And AI, by design, has no humanity.”