Harvard University’s Newell boathouse is a grand but garish building wedged between Boston’s Charles River and a six- lane highway. With its crimson-bricked facade and symmetrical pointy-hat roofs, tall pillars and star above the entrance, it gives off an aura of gothic leisure centre. Inside, it is packed to the rafters with long, wooden hulls: daily equipment of the men’s varsity rowing team. It is also the birthplace of Strava. Yes, that’s right: for all its prominence among cyclists and runners, Strava, the world’s biggest exercise app, began with a pair of rowers.

Michael Horvath and Mark Gainey met on the crew team in the late 1980s. Both athletic and academically astute, the duo spent hours hanging out around the boathouse, poring over their training and chatting with their team-mates. “The mood was festive and fun,” Horvath, now 57, tells Cycling Weekly, but they knew the days were numbered. Before long, the pair were plucked from the water and thrust into the real world. Horvath became an economics professor; Gainey, an art history student, went into private equity.

The two rowers remained close friends in the years after they graduated. Gainey would spend time with Horvath in his office at Stanford University, a ploy to pinch his internet connection, but also a chance to natter away like in their boathouse days. Over time, Horvath says, the duo grew interested in the idea of starting a company together. “We hit upon the idea of the ‘virtual locker room’ – a website where we could try to get the feeling of being on the crew team back, by interacting with other active people around our workouts. We missed our crew team-mates, missed the daily motivation to workout and excel at rowing.” And so the pair began to sketch out a business plan.

It’s an origin story not dissimilar to that of Facebook – a tale of two friends at an elite Ivy League university who started a social media platform that would turn into a behemoth. Today, the company Horvath and Gainey created, Strava, is the must-have exercise-sharing app, a cyclist’s companion, with over 120 million users ranged across more than 190 countries. The journey to the top was an uphill battle, threatened by a negligence lawsuit, followed by many years of failing to make a profit. Ultimately, Strava’s story is that of the start-up that took over the world.

The revolution begins

After the idea of the virtual locker room first took root in 1995, over a decade would pass before Strava actually came to life. Originally, Horvath and Gainey launched an email software business, which grew to over 1,200 employees but never became profitable. “There was still the underlying problem in our lives that we wanted to be more active, but lacked the motivation we remembered from our crew team together. Strava’s mission mattered to us personally,” says Horvath.

In 2008, following the advent of GPS, smartphones and Garmin technology, the pair turned back to their original locker room idea. Suddenly, it was feasible. They launched a demo website, green in colour, with a leaderboard of just a handful of segments in Vermont and California.

The duo then encouraged their friends to post their times, and handed out prizes including free sets of wheels. Such was the appeal that some called in sick to their jobs so they could ride. The idea, they quickly realised, was a good one.

The following year, Strava – coming from sträva, ‘strive’ in Swedish, Horvath’s mother tongue – went live. “We launched Strava into a pretty crowded, competitive landscape,” Horvath says. “There were already plenty of ways to track your run or ride in 2009. We knew our ability to grow and thrive centred on delivering something different, built around the community of active people Strava could connect you to.” Paul Delani, a cycling coach at Trainsharp, remembers being one of the early users. The platform, he says, felt “revolutionary”. “When I first started to use it, I was like, ‘OK, this is something different.’ It gave you an ability to race yourself, which you couldn’t really do before, unless you were timing yourself between lamp posts or town signs,” he adds. “The fact you could even see where you rode. The Garmin software at the time was pretty basic in comparison. I was like, ‘Crikey, I’ve got a map, I can see my average speed, I can see my power data’.”

To better understand the public consensus around Strava, we asked you, Cycling Weekly readers, for your thoughts on the app. Your answers were mixed.

“If it ain’t on Strava, it didn’t happen,” said keen user Ben Culverhouse, repeating a popular adage. For some of you, the app provides motivation, an impetus to get outside, clock up the miles, and go a little bit faster. “I am 66,” wrote Debra Valentine, “and I like to see on Strava that I can still get an achievement on a ride I do regularly. It helps me see that I am not losing fitness as I age.”

For others, Strava’s competitive element has had the opposite effect and has proven a turn- off. “I used to use it all the time but found myself spoiling my rides,” said Stuart Smith. “I was competing with myself and others all the time. Now, I ride all the time, but listen to my body, so as to enjoy the ride, without Strava.”

Another reader, Frank Chan, echoed Smith’s sentiment. “I don’t need to compare or check anyone else’s data or fastest times for segments,” he wrote. “I have enough competition in other aspects of life and can be super-competitive. Using Strava would be like a gambler going to the casino.”

Fuelling competition

From the start, Strava’s flagship product was its leaderboards, which brought with them the titles of King and Queen of the Mountains – KOM and QOM. They were the brainchild of Davis Kitchel, a friend of Horvath’s, who had been recording his hill-climbing times on strips of paper and keeping them in his jersey pocket.

When Kitchel later discovered a way to digitally rank them, he found the tables fuelled competitiveness, not just against others, but against himself too. But these leaderboards would give rise to sneaky behaviour. “I used to live on the south coast of England,” says coach Delani, “and there was somebody who was quite well known for, if there was a tailwind on this certain segment, at midnight, they’d go out to try and get that KOM. If somebody had taken their KOM, you could almost guarantee they’d be out that afternoon to try and take it back. That’s not healthy.”

In 2010, one alleged KOM pursuit ended fatally. Eighteen months after Strava launched, a 41-year-old cyclist from California hit a car and died while bombing downhill. The speed limit on the road was 30mph; he had recorded almost 50mph there in the days leading up to his death. The man’s parents decided to sue Strava, claiming the app was negligent in encouraging such behaviours. A hefty payout, particularly for a company still in its infancy, could have put a pin in the whole project. The case, however, ended in relief for Horvath. “It got ruled that, when you go out and you’re exercising, you’re assuming the risk of what activity you’re doing,” he told CyclingTips in 2020. Still, having made Strava with honest intentions, the founders were suddenly seeing the emergence of a more insidious element. “We were found not responsible. But inside the company, in terms of the things we had to think through, we realised we needed to understand much more clearly, especially in the United States, what the laws were around things like liability,” Horvath said.

It would not be the last time alleged KOM-chasing ended in death. Less than two years later, not far from Strava’s HQ in San Francisco, a man ran three sets of red lights while going for a personal best and ploughed through a crossing into a 71-year-old man, who died four days later. This time, Strava was not involved in the legal case. It ended in the cyclist pleading guilty to vehicular manslaughter, a first- of-its-kind conviction in the US.

Of the around 40 million women on Strava, Illi Gardner has the most QOM trophies. The current British hill-climb champion, she was coincidentally brought up in the app’s home state of California.

At just 24 years old, Gardner boasts the best female time on over 9,000 segments, including legendary Tour de France climbs including Alpe d’Huez, Mont Ventoux and the Col du Tourmalet. For her, QOM hunting is a lifestyle. Why does she like it so much? “It’s just fun,” she tells Cycling Weekly with a chuckle. After six years of road racing, Gardner was tired of feeling “terrified the whole time” jostling inside the peloton, and switched to a life of solo climbing. “I think I’ve always liked doing things quietly, just because it kind of takes the pressure off,” she says. “It’s just you and the hill. Strava provides a good platform to compare yourself with others, and when I started actually being able to get QOMs, that definitely provided a lot of motivation.” Still, she says, “you also have to take it with a pinch of salt.”

Indeed, Gardner has heard stories of women getting men to pace them up climbs in search of QOM trophies, a ploy that’s very much against the hunting spirit. The only help she’s ever had, she explains, is from her dad, who sprayed water on her when she took the crown on Mont Ventoux.

Knickerbocker glory

Meanwhile, Strava was rapidly growing. After it launched as a mobile app in the summer of 2011, popularity soared. No longer did people have to upload their ride data manually; now, they could track it all easily on their phone. The company went from seeing hundreds of users signing up every day, to thousands, logging millions of activities. And yet, curiously, Strava couldn’t turn a profit.

Horvath stepped down as CEO in 2013 to care for his four children and terminally ill wife, and when he returned in 2019, the business was still to make a penny, despite counting over 40 million users. Gareth Nettleton, the head of marketing at the time, remembers the alarm being raised. “I think any business that doesn’t make money in the long term can’t survive. You can’t live like that forever,” Nettleton says. “I remember having an all-hands meeting the day after Michael came back, and he said to the company, ‘Put your hand up if you’re working on the subscription business today.’ I reckon 10% of the company put their hand up. Then he said, ‘Cool. From tomorrow, you’re all working on the subscription part of the company.’ It was amazingly clarifying, and we then went on the most focused six-month period of my entire career.”

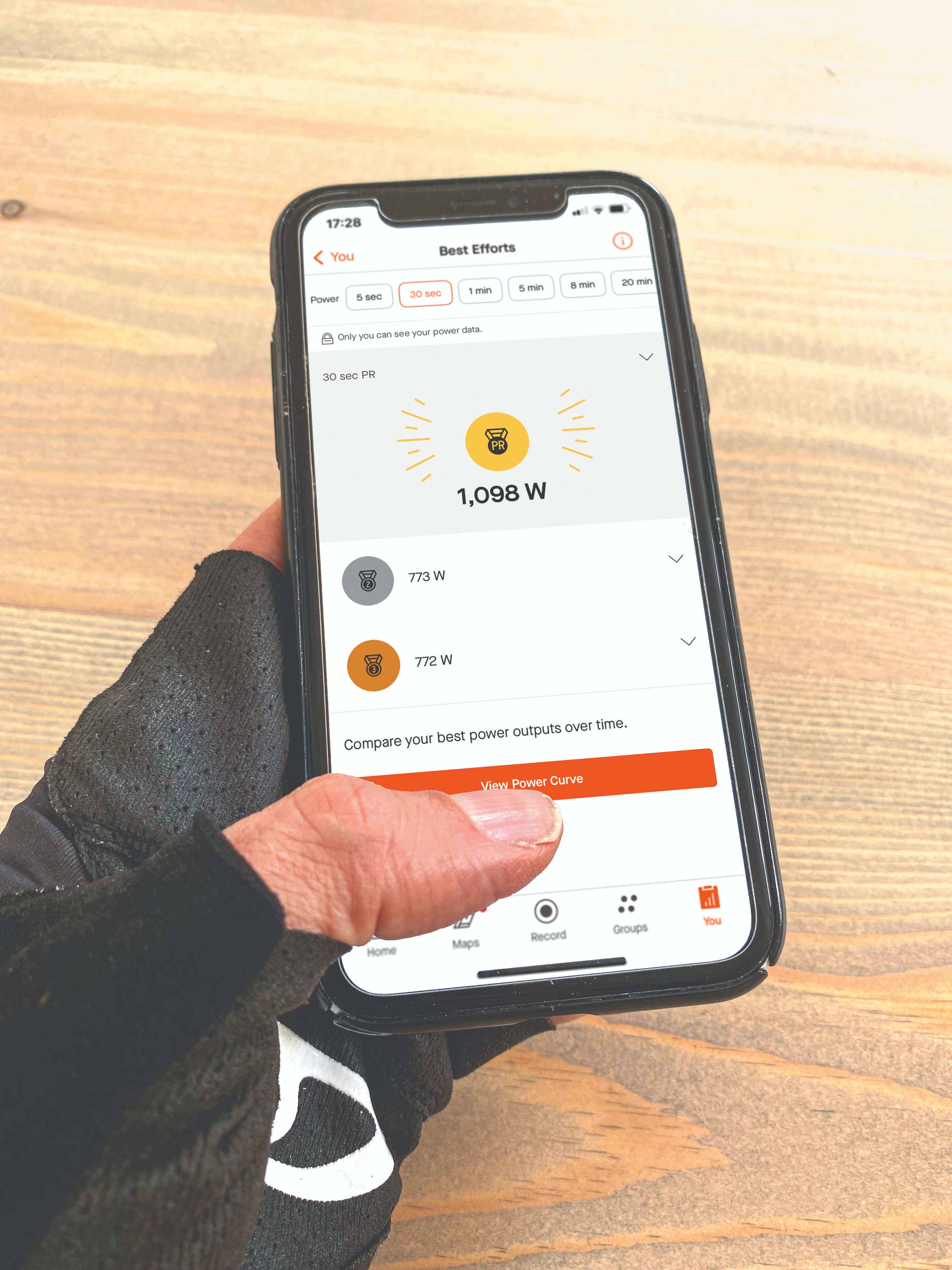

Until then, the subscription offering was slim, and free users could access most of what the app offered. Nettleton and his team started to look at the best features, those people interacted with most, and hid them behind the paywall. Among the first to go subscriber-only were the leaderboards. “The analogy I always used is that the subscription has to be the ice cream, it can’t just be the cherry on the top,” he says. “It has to be some absolutely core stuff that everybody finds value in. If you only make it the cherry on the top, you never convince enough people to become subscribers.”

They planned to launch the premium model in April 2020. Just weeks before, though, the world fell under the cloud of a global pandemic. Covid, generally, proved a disaster for already unprofitable businesses. For Strava, the timing couldn’t have been better. “The number of brand- new people around the world joining Strava had never been faster,” Nettleton says. With more free time, people turned to exercise, all the while craving social interaction. Strava offered the perfect cocktail. “The pandemic was this huge accelerant. ‘A tailwind,’ we called it. In a lot of ways we were fabulously lucky,” Nettleton adds. Thanks to the influx of users, the success of the subscription launch was unprecedented. Strava achieved cash flow breakeven “within a few months”. Finally, the profits came.

When Nettleton joined Strava in 2013, the app had around two million users, with “a couple of hundred thousand” paid subscribers. When he left in 2021, those numbers had multiplied fiftyfold, up to nearly 100 million users and subscribers “significantly in the millions”. So taxing was his role, though, that Nettleton decided to take a six-month break when he left the company. “I’ll be honest, I was really burnt out,” he says. “I was exhausted, totally exhausted, both mentally and physically.”

As a location-tracking app, Strava has had its fair share of privacy controversies over the years. In 2018, its heat maps tool revealed secret US military bases in Afghanistan, after it highlighted an area where soldiers had been tracking their exercise. More recently, the app has given rise to fears of stalking, its ‘Flyby’ feature allowing users to see who ‘flew by’ them during an activity. This feature is now opt-in only.

To keep your data private, head to ‘Privacy Controls’ under the settings cog, where you can limit who sees your profile and activities. You can either be open to the public, followers only, or totally private, keeping the app as a personal training log. It’s worth bearing in mind that, if you want your times on a certain ride to appear on leaderboards, the activity must be public, for all to see.

Strava also allows users to hide their start and end points, so others can’t pinpoint their address – so you don’t have to broadcast where your pride and joy spends its downtime.

Breaking even

So where is Strava now? Although the company is privately held, and therefore not required to share its financial data, market researchers Sacra estimate it to have generated over £200 million in revenue in 2023, valuing it at £1.2 billion. What this means is that, after years of venture capital support, Strava is finally standing on its own two feet, and even starting to run. Business decisions, though, have continued to be cutthroat. Today, that part of the company is headed up by Zipporah Allen, familiarly known as Zip, and formerly of fast food chains Pizza Hut and Taco Bell. “I just pinch myself sometimes,” she says of her current role, but despite her infectious smile, it’s not easy to keep everyone happy.

At the start of last year, controversy brewed around price hikes, which saw UK monthly subscribers facing a 28% increase, from £6.99 to £8.99. Updates from the company were patchy, with pricing scales differing from country to country, and customers left feeling confused. “We never wanted to catch out our community,” says Allen, “but I think it’s fair to say we did not do a great job of communicating in a way that our community could understand.”

The hikes came just months after Strava made headlines for laying off a chunk of its workforce – 38 people to be exact, or 15%. Was this a sign of a business back on the ropes? “It was a restructuring of the company to be more efficient based on the economic environment of the industry,” Allen says. She then shifts her tone. “What’s exciting is that we’re accelerating our growth.” Today, she adds, Strava is “seeing those returns” from the restructure. “We don’t share specifics, but I can tell you that our business has accelerated meaningfully.” Is she happy with where the company is heading? “Uh huh,” she nods with a smile.

And there is plenty to be happy about. Despite its challenges, Strava has never stopped gathering pace. What began as a simple cycling website between friends, now counts almost 50 sports, and is welcoming new users at a rate of over a million per month. Most just share their rides or runs, others obsess over it, hitting records each time they rise from the sofa. Earlier this year, one woman went as far as to share her five-and-a-half- hour “workout” of giving birth.

At the start of this year, Horvath was replaced as CEO by former YouTube executive Michael Martin. The company needed someone “with the experience and skills to help us make the most of this next chapter,” Horvath wrote. Although neither of the Harvard University rowers remain at the helm, they are both still involved in the business. What they created ended up being a lot more than a virtual locker room. They built an exercise empire, both a community of athletes, and, at the same time, an addictive social media dopamine machine. If Strava’s past is anything to go by, the next chapter will be filled with twists and turns.