It's a quiet weekday morning in a side street in the health precinct of Deakin, and Glenn Keys is in celebration mode.

It's muted, of course; celebrating a seemingly constant stream of health emergencies and human strife is hardly the done thing.

And yet Aspen Medical, the health service he co-founded 20 years ago, has reached heights he never dreamed were possible back when he was preparing his first tender at his kitchen table.

Today, his head is chock-full of numbers. Personnel, births, deaths, PPE kits, vaccinations, knee operations, epic hospital waiting lists - he can rattle off the figures for just about any health dilemma, global, regional or local, so long as his company has been involved.

And, after two decades, Aspen has found itself in a very large number of health situations.

'We go where we're needed'

Perhaps "found itself" is disingenuous for a commercial operation, although Aspen does have a habit of appearing, Forrest Gump-like, at the coalface of the emergency healthcare world where things are happening.

Ebola, Afghanistan, Somalia, the Solomon Islands. Orthopaedic surgeries in Northern England. Prison waiting lists for dental services in New South Wales prisons.

Not to mention, of course, COVID, the greatest health crisis in most of our lifetimes.

At the time of our conversation, preparations are in train just a few kilometres away from Aspen's Deakin headquarters to begin dismantling one of the territory's most visible pandemic measures, the Canberra Hospital's $23 million pop-up emergency coronavirus department.

It's as sure a sign as any we're now in the post-COVID era. But Aspen was tasked with setting it up in 2020, at a time when images of temporary morgues and hastily dug mass graves from Europe and the US were beamed around the world.

They built it on Garran Oval in just 37 days. The centre was soon repurposed as a testing and vaccination facility; most Canberrans had cause to pass through it at least once during the pandemic.

Seeing Aspen pop up just at the right time was and is entirely expected, but Keys is at pains to point out that his company's ubiquity is as much to do with the hard slog of applying for tenders as its reliable track record.

"What we do is go where areas are under-resourced and have an urgent need," he says.

"That may be in the developed world, it may be in the developing world. But it's really around where we're needed."

Back at home

This means, inevitably, working in remote parts of Australia; Aspen supports the Remote Area Health Corps, primarily in the Northern Territory, and has provided, by Keys' prodigious memory, more than 8,500 staff into remote indigenous communities in the last decade.

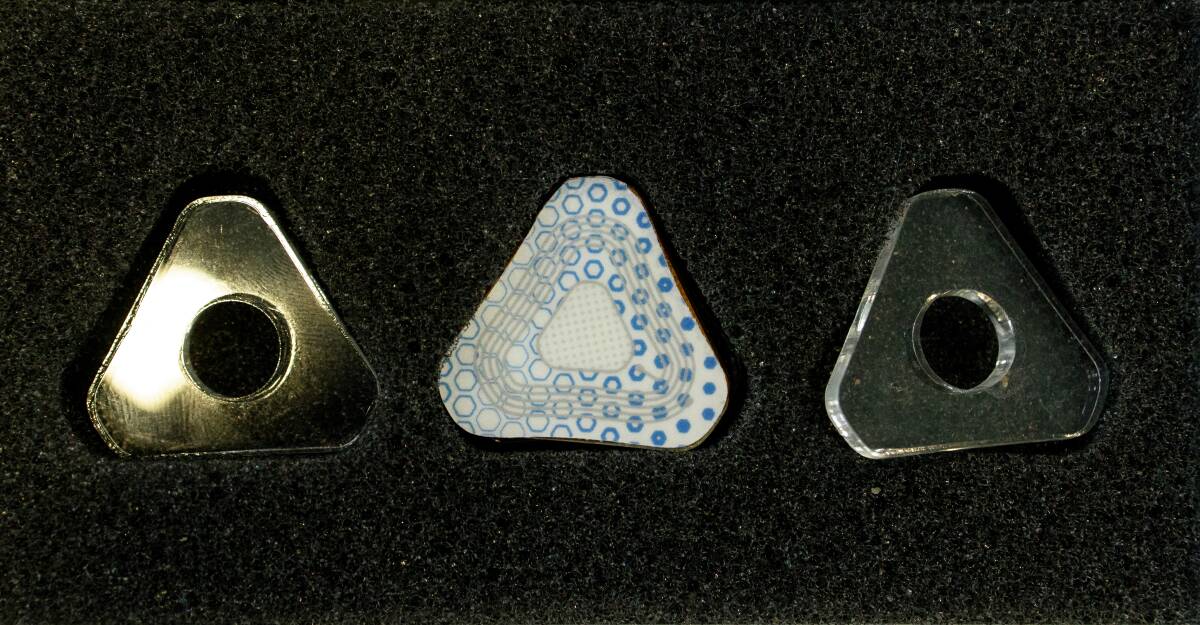

The company is also moving into the technology sector, investing, for example, in Wear Optimo, a small device worn on the skin that can track a patient's dehydration levels.

"It's some of the most advanced tech in this area in the world. And it's not just hydration - the next one is around troponin, which is what happens when you have a heart attack," he says.

"We're both an investor in it, because that's how committed we are to the tech - it's an Australian company, Australian research ... but also, we see enormous applicability for our customers."

Early beginnings

Keys came to co-found Aspen after a military career. He went through Duntroon and studied mechanical engineering at UNSW in Canberra, as well as aeronautical engineering and flight-test engineering in England.

He eventually settled here with his family. Today, Aspen has 6000 staff in 20 countries, and Keys has just turned 60.

"It feels almost surreal, to be honest, because that assumes I was 20 years younger when I started this," he says.

The company's first contract was a consultancy to review how to reduce surgery waiting lists in the United Kingdom. That led to another contract to deliver the solution they'd come up with.

It all sounds embarrassingly simple, 20 years on, in the context of more complicated projects involving war zones, emergency services and entire new hospitals.

But it did involve a certain amount of persuasion, and outside-the-box solutions.

In the end, it boiled down to a proposal to perform surgeries outside the established nine-to-five office hours.

"We cleared 12,000 orthopaedic procedures in 12 months," he says.

International challenges

Back when he and former business partner Andrew Walker set up the company, they wanted the most healthful-sounding name they could think of.

"If you close your eyes and you think 'Aspen', you think of a ski resort, where everyone's fit and healthy and happy," he says. The company's logo is a correspondingly fresh blue-and-white motif.

And yet, Aspen is frequently sending people to places that are not clean, healthy or happy at all; one of their earliest contracts was providing healthcare to the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands.

In 2014, Aspen helped manage the Australian government's response to the ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. In 2016, it was the world's first commercial company contracted by the World Health Organisation, to manage and resource a trauma field hospital and maternity unit.

They ultimately established three hospitals and transitioned them to the local Iraqi provincial health department.

And as Kabul fell, Aspen organised - in 72 hours - a hospital clinic in the United Arab Emirates for Afghani evacuees bound for Australia. It's also setting up two major hospitals in Fiji, and has personnel in Mogadishu, Somalia, providing healthcare to UN staff on a five-year contract.

A contract, Keys points out, for which Aspen won the tender, after which they were given just 25 days to mobilise. This meant getting 36 clinical staff into one of the least safe countries in the world and ready to work.

COVID measures here in Australia aside, much of Aspen's work happens in the developing world, a far cry from the dysfunctional waiting lists of English hospitals.

"What we've done is found a way where we can deliver the care that's delivered in a humanitarian space, but with the standards of the developed world, and it's pretty unique," he says.

Aspen is, in essence, an Australian company that exports healthcare, and makes money from it. But Keys shrugs off any criticism of the ethics involved.

"I think the language is starting to evolve in this sector," he says.

"It used to be not-for-profit and for-profit. It's now evolving into profit-for-purpose, and not-for-profit. You go away and have a look at any of the international NGOs in their annual report, and they'll tell you what their margin is, because they put a margin on everything, they don't do it for free.

"It's just the last bastion has been health, and we're in that sector."

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.