Pogradec, Albania – Almost every evening during the summer of 1975, Bajram Fezollari’s father, Feridon, would take him on a walk along the banks of Lake Ohrid.

But these were not simply strolls for bonding purposes between a once-distant father who had spent more than a decade behind bars and his teenage son. In reality, the two were on a stealth mission.

On and off for four years, Feridon had been strolling along the Pogradec lakeside, meticulously monitoring how and when the police patrolled the waters and the surrounding area.

He observed how many guards were on duty at any given time, when they would change over, how many lights they would project onto the lake at night, and from what positions.

Then, one night in the summer of 1975, after years of watching and months of planning, the family made their move for freedom from the political persecution they had endured for years.

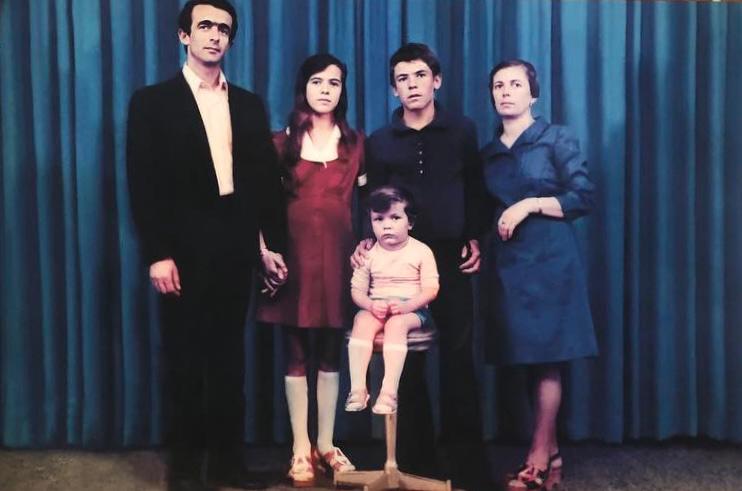

Feridon, a 16-year-old Bajram and 14 members of their extended family set out in the dead of night, boarded a wooden boat they had built themselves and made a gruelling, eight-hour journey across the lake to what is now North Macedonia in neighbouring Yugoslavia, before eventually travelling to Australia where they claimed political asylum and made a new life.

No exit

Nearly 50 years since that night, Bajram stands at the bar he now owns on the banks of Lake Ohrid and recalls the journey his family took from this same spot – one that turned into a round-trip decades later when he decided to return.

When the Fezollaris left Albania, the country was in the iron grip of dictator Enver Hoxha, under whom, for more than 40 years, it became one of the most isolated and repressive places in the world.

During the communist regime, which lasted from 1945 to 1991, emigration from Albania was officially prohibited and anyone caught trying to leave the country could be shot or punished with prison terms of anything from 10 to 25 years.

According to a recently disclosed November 1990 Ministry of Interior document marked “Top Secret” and signed by the minister at the time, Hekuran Isai: “From 1944–1989, the number of people escaping from Albania were 13,692 people, of whom 988 died.”

Even in 1990, by which time restrictions had been somewhat eased, 54 people were killed at Albanian borders – although the identities of those responsible have never been made clear.

Along border areas like Lake Ohrid, guards would patrol, tasked with not allowing anyone to leave. In some cases, they were even instructed to shoot those caught trying.

“When I think back, our chances of not being detected by the guards or drowning [the night we left] were a mere 5 percent,” Bajram says now, reflecting on how lucky they were to have made it out.

A ‘segmented’ brain drain

Emigration among Albanians is not new. Like the Fezollaris in the 1970s and, later, other families who moved when the country opened up to the world in the 1990s, people have regularly been on the move.

According to data from the Albanian Institute of Statistics and the United Nations, from the fall of communism in 1991 until 2022, more than a third of the population is thought to have left the country. Between 1.2 million to 1.4 million people left Albania in that time, while the population has fallen from 3.3 million in 1991 to 2.8 million overall in 2023.

By 2011, Albanians had gained the right to travel visa-free to the European Schengen area, and in recent years, professionals have been given the right to work in some countries such as Germany.

Today, it is estimated that 42,000 Albanians migrate each year. Young professionals such as doctors and nurses are those who do so the most, creating a void in the country, which is proving difficult to fill.

A report on this issue by the University of Sussex in 2023 concluded, “This loss of doctors represents a massive loss of both human capital and investment in the production of that human capital.”

The longer-term trend of migration for Albanians has persisted despite the fact they have not always been warmly welcomed in other countries. In 2022 and 2023, Albanian migration to the United Kingdom was thrust into the spotlight when the British government raised the alarm about the numbers crossing the perilous English Channel in small boats.

In 2023, the flow of Albanian asylum seekers towards the UK saw a significant decrease, partly because of measures taken by the governments of both countries. But the racism and violence that many endure have persisted.

None of this has stopped Albanian emigration, however. The study by the University of Sussex found that “Most Albanian emigrant doctors do not plan to return to Albania. The obstacles deterring return are more or less the same as those driving emigration. [There is a] general feeling that ‘there is no future in Albania’.”

A few like Bajram, however, have bucked this trend.

A disillusioned Communist

On the banks of Lake Ohrid in Pogradec, Bajram sits at the bar he now owns there and recalls the journey he and his family made in the dead of night nearly five decades ago.

“The waters in the dark resembled a monstrous creature with its jaws wide open ready to engulf us all,” he says, lost in thought, as he recounts the details of their escape and the decades-old saga of persecution that led them to the lakeshore to begin with.

The story of the Fezollaris starts with Bajram’s grandfather, Haki Fezollari.

During World War II, Haki fought as one of the communist partisans who liberated Albania from the German Nazis in 1944. But by 1949, he had grown sceptical of the communist regime’s rise to power. According to his son, Haki had believed that he and his communist comrades would build a new, free and democratic society. He was quickly disillusioned when he saw how Hoxha had isolated the country and installed a brutal regime where freedom of speech and other basic human rights were completely denied.

So, with a group of friends, Haki decided to leave the country and get as far away as possible. They chose Australia, where they planned to actively oppose the regime from abroad, as the least likely place for Albanian spies to be able to catch up with them.

Haki and his band of friends managed to sneak across the land border with Yugoslavia in these early years when border control was not as tight as it would become in the 1950s.

But when he left, his wife and four children – the eldest of whom was Feridon – were left to face the repercussions of his escape. Individuals whose family members were accused of having turned against the state faced stigma and punishment.

After Haki left, Kushe bore “internment” and poverty as punishment for her husband’s actions. Under internment, she and her family were sent to remote parts of the country where she was forced to do physical labour on farms or construction sites for very minimal pay; when she returned home to Pogradec, she would collect and sell wild medicinal plants to make a living – in secret, as no private sector business was allowed.

Kushe did not have a formal education – she never learned to read or write – and, as a result of Haki’s actions, things like higher education became off-limits to his children and grandchildren, as well. As second-class citizens because of their “traitor” father, there was no chance that his offspring would be accepted into university – a privilege set aside only for those with the most unblemished of records.

To help Kushe run the house and put food on the table, Feridon started working at the age of 15, heating limestones to produce lime in the hills of Pogradec. He married at 19 and he and his wife had three children including Bajram.

Kushe had lost hope of ever seeing her husband again but was sometimes comforted by letters he would send from Melbourne. Because she couldn’t read, Bajram would read them to her.

He never forgot those letters, despite the meagre details they contained – the family knew the regime would open and read them first. Alongside Haki’s words “I hope you are doing well and nobody has died” were the postcards he always sent showing scenes from his new life in Australia.

Bajram was amazed by the printed images depicting the roads of Melbourne teeming with cars and ships lining the shores. Later, during the early 1970s, he was awe-struck by the ones showing the stunning, newly built Sydney Opera House.

Feridon missed his father and, in his dreams, he and his new family would join him in Australia one day. But sharing this dream with a friend was the one grave mistake he made. His friend had been spying on him and reporting to the authorities, which led to Feridon being jailed in 1961, leaving his pregnant wife, Sevika, daughter Nuria and a two-year-old Bajram.

Feridon was sentenced to 13 years in prison, convicted of planning to escape Albania, and spent 10 and a half years behind bars. When he was released in 1971, Bajram was 13 years old. He came out of jail determined to no longer speak about his dreams to anyone, but instead to work to make them come true.

An opportunity for escape

Almost as soon as Feridon was released, he began planning an escape. He went on reconnaissance strolls along the lakeside with Bajram and noted that the guards were very organised, except at the beginning of July.

It was at this time of year that the sleepy town by the lake would receive a very special guest – Enver Hoxha himself. The dictator was fond of Pogradec and would spend summer holidays at his house near the lake.

Bajram, who accompanied his father during their monitoring missions, recalls that when Hoxha was holidaying in the town, the guards gathered around his residence to reinforce security there. They also used their spotlights less frequently in the area surrounding the lake.

“They would avoid disturbing the leader’s sleep with the intense beams of light that they cast upon the lake,” he explains.

This helped Feridon pinpoint the optimal moment for the escape. However, he was not clear on the means or who would be able to join him. Feridon lived in the family house with Kushe, Sevika, and his three children. But they also shared it with his brother, Ethem, his wife and one child, and his other brother Beshir, his wife and two children. Their sister Myrvet also lived not far away, with her two children.

Feridon discussed the escape plan with his mother and brothers, in the presence of Bajram, who was 16 at that time. “[My grandmother] urged my father to take us all on this journey – everyone or none at all,” he recalls.

After being abandoned by her own husband, he says, “She knew exactly what would happen to those left behind.” Kushe knew that if Feridon and her other two sons left alone, their wives and children would be placed under internment and forced labour, just as she had been.

Looking back, Bajram says now: “If she didn’t insist, we wouldn’t have the good life we enjoy today. I’m sure the regime would have broken our spirit and energy in retaliation for our fathers’ escape.”

Tree trunks and a tablecloth

To build their boat, they used one large, four-metre-long (13-foot-long) waterproof tablecloth that also circled the hull. Some tree trunks, felled from a forest near their house, were cut into planks to form the boat. These were linked together with ropes and metal wire. The brothers put it together in nine days; however, they assembled and disassembled it many times to transport the pieces and hide them near the lakeshore, where it would be reconstructed on the night of departure.

At 1am on departure day – July 3, 1975 – Bajram went to a hill across Lake Ohrid, to undertake the most important task of his life: guarding the pieces of the boat that were stashed in the surrounding bushes.

After 18 hours on guard duty, when the day turned to night, Bajram’s family members – in small groups, out of fear of being spotted – began joining him on the hill. Around 8pm, the men started putting the pieces of the boat together, while the women prepared the children for the journey. After about three hours, at 11pm, they were finally ready to go.

The distance from the hill to the lakeshore was no more than one kilometre (0.62 miles), but it was a dangerous trip on which they risked detection. Two of the men carried the boat, followed by the other family members walking in silence in single file. The family carried no luggage.

It was a little after midnight on July 4 when the boat hit the water and the eight adults and eight children – including one six-month-old baby – pushed off into the lake’s waters.

Bajram and his uncles took charge of propelling and rowing for the eight hours it took to reach the far end of the lake. In the pitch black, the rhythmic strokes of the oars would occasionally be accompanied by Kushe softly murmuring prayers and the soothing lullabies the women sang to hush the restless children.

“I would focus solely on pushing forward the boat and keep my head held high,” Bajram recalls, gesturing with his arms, his posture straight, as if transported from his seat at his lakeside bar to the boat he sat in all those years ago.

Terrified of being spotted by the police that night, young Bajram’s mind found refuge in the images on the postcards his grandfather had sent. “I would occupy the long hours by dreaming [I was] in the bustling streets of Melbourne or entering Sydney’s Opera House,” he says.

At around 8am on the morning of July 4, 1975, they finally arrived on the shore of Struga in Yugoslavia, at the northern end of the lake.

When the family disembarked on the shore that morning, the first thing they did was embrace one another, Bajram recalls. “Only God knows how we made it,” he says now. “Even a Hollywood movie couldn’t do justice to that journey.”

Culture shock

After being taken to a camp and questioned by local police, the family stayed in Yugoslavia for 56 days before finally leaving for Australia, where they were granted political refugee status and provided with modest public housing they shared with other refugees from different countries.

Right from the start, life in Melbourne was challenging, Bajram says.

While Bajram does not feel that racism ever posed much of a problem for his family, his parents and uncles found it immensely difficult to adapt to the Australian lifestyle.

The family group had come from a very isolated country and was thrown into a bustling, modern city where they did not speak the language. As a teenager able to pick up English more quickly, Bajram became responsible for earning money. He started working in factories.

Very quickly, he realised he had a nose for business. In one factory where he worked, he started selling ice creams to his co-workers during lunch, at a cheaper price than the ones being sold at the canteen. Later, he sold them custom-made clothes. Eventually, he made the bold decision to buy a small textile factory.

Many people in the community thought it was a crazy and reckless idea, he says now. Most preferred the stable life that a monthly salary could provide. But he followed his business intuition and it worked.

“I was living all that good life that big cities of Australia had to offer,” he says, smiling. “I had fancy cars and was going to nice bars and clubs. It was exactly that good life that capitalism created during the ’80s in developed countries.”

Despite the sense of gratitude that Bajram says he still feels for Australia, which enabled him to flourish, he remained deeply tied to his home. During a short summer visit to see relatives in Struga in the 1980s, he met an Albanian, fell in love, married, and brought her to Australia.

“Deep down, I simply couldn’t disconnect myself from my roots,” Bajram says, smiling, with his wife, Asije, nodding in agreement beside him.

Communism falls

While the Fezollaris were building their new lives abroad, the decades brought political change at home in Albania.

In 1991, the communist regime built by Hoxha – who had died in 1985 – collapsed. The country also experienced regional upheaval as the former Yugoslavia had begun to dissolve by the beginning of the 1990s, leading to the separation of countries like Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and tension and unrest in Kosovo, the former province of Yugoslavia predominantly inhabited by Albanians.

Many Albanians had high hopes for a brighter future and people embraced democracy and free trade with a new-found sense of freedom, able to shape the lives they wanted for themselves.

But most people were still employed by state-owned farms and factories, many of which went bankrupt, leading to thousands of lost jobs and livelihoods. The privatisation process and land reforms that followed were slow.

Once again, many turned to emigration as a solution, leaving for neighbouring developed countries, and then for the rest of Western Europe and beyond.

But while more than a million people flowed out of the country, now that the borders were open, Bajram’s parents decided to use the opportunity to return.

At home in Melbourne in 1992, Bajram booked a plane ticket to Tirana, as he watched an Australian TV report about the challenges Albanians were facing following the collapse of communism, including the hardships of those crossing the border on foot and in boats in search of jobs.

But he remained optimistic. In 1991 and 1992, once Hoxha’s successor, Ramiz Alia, had lost his grip on power, Bajram and his brother Lirim made several trips back to explore business opportunities. After the success of the textile factory in Australia, they decided to transfer much of their capital to Albania and finally decided to move back in 1992 – something Bajram now considers the best choice he has ever made.

Today, Bajram mainly resides in his hometown of Pogradec, while Lirim lives in Tirana. Some of their family members moved back, as well, including Bajram’s three sons who had been born in Australia. Kushe was the first to come home, but died soon after her return to Pogradec in the mid-1990s.

Her husband, Haki, died in Australia in 1992 and the family returned his body home to be buried. Feridon, Bajram’s father returned with them to Albania in 1992, and died in 2002 in Pogradec.

Today, the family’s operations in the import-export sector expand across the Balkans.

But Pogradec has remained home. It has been there that, for 25 years now, Bajram has run a TV station from the town to give a voice to the local community, as well as his busy bar and restaurant across the lake.

“I have seen the world and taken some of the best that it has to offer,” Bajram says. “I was even once offered to work as a manager in Miami Beach, but I said, ‘Sorry, I’ve chosen Pogradec Beach.’”

When his family left, they did it to escape oppression, not to escape Albania, he says.