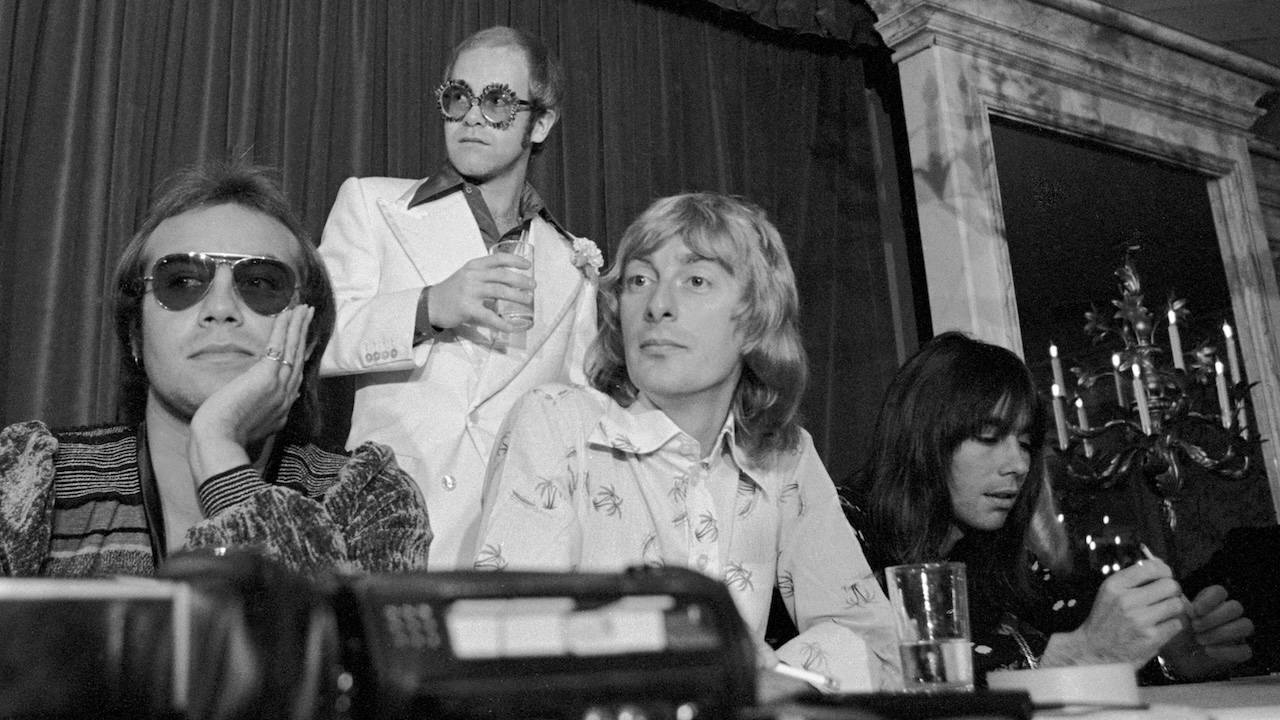

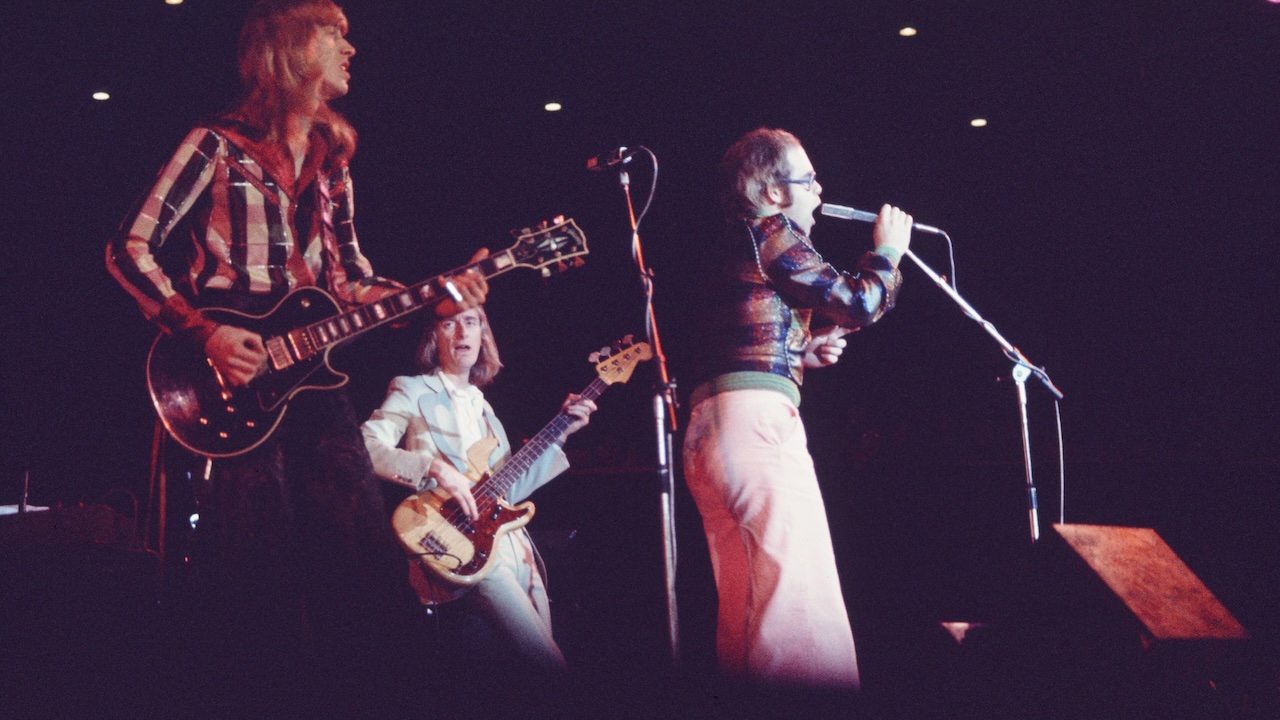

With his enormous catalog of hit songs and even larger public persona, Elton John has kept audiences enthralled since he first emerged in the late '60s. For his first few records, he turned to various hired guns for stage and studio work, but his decision in 1971 to form a full-time band proved to be a wise one, leading to a string of massively successful albums and tours.

On bass guitar, Dee Murray developed a style that built on the melodic approach Paul McCartney had perfected with the Beatles. “Dee's a player who's been really overlooked,” Davey Johnstone, longtime Elton John guitar guru, told Bass Player. “He was such a fluid player, with beautiful musical ideas.”

Murray was also the last bassist ever to play onstage with John Lennon, in a 1974 Elton John concert at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. The performance was captured on Here and There.

Between 1971 and 1975, Murray anchored what would become Elton John's most celebrated albums, including the 1973 double album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. The centerpiece of that record's hat trick of hit songs (sandwiched between Candle in the Wind and the title track), Bennie and the Jets captures the spirit of pop glitz and glamour that Elton John came to embody. It also presents a concise primer of Dee Murray's quirky bass craft.

“We thought Bennie and the Jets was a really odd song,” said Johnstone. “We never thought in a million years it would be a single.

“Producer Gus Dudgeon was responsible for the song's sound. He used the audience from Jimi Hendrix's performance on the Isle of Wight to kick it off – that's the audience clapping for Jimi to come back onstage. And he put that weird ambience on Nigel's drums.”

“We did it in one or two takes. Your first ideas are usually your best; if you belabor them, they start to sound pretentious. Yellow Brick Road was a double album, and we did it in 16 days! That's the magic you get with a band like that.

“It always worked the same way: Bernie Taupin would bring in the lyrics, and Elton would have a go at it. If he didn't have anything within 20 minutes, he'd stop. Most of the big songs were written inside 15 or 20 minutes.”

Judging from the first four bars of music, there's not much to Murray's bassline in Bennie and the Jets. After all, anyone can play staccato downbeats at this tempo, right? Well, not really. In analysing any bassline, it's important to pay attention to note length. Here, it's absolutely crucial.

Compare, for instance, the duration of the intro's downbeats to those in the first verse. Letting the A in bar 5 ring all the way through to beat two (likewise, the D through to beat four), Murray imparts a loping swing that contrasts perfectly with the staccato downbeats of the intro and choruses.

Other hallmarks of Murray's style include his use of ghost and grace notes. The first one comes in the first chorus, at 00:59. Grab that G grace note with the same finger you use to play the C 16th note in beat four, raking your plucking finger across the strings. At 01:09, Murray plays another cool figure, 16th-note triplets into the downbeats under the D and Em chords.

When Elton launches into his piano solo at 02:38, Murray refuses to be left in the dust, keeping up with some melodic forays of his own. “Elton was always happy to let us play whatever we want. As much as he loves the big, fat whole-notes, he always encouraged us to go out on a limb, because he does, himself.”

Following the descending fill in the forth beat of the bar at 03:25, Murray almost misses the next downbeat, sliding down into C in the nick of time. What results is one of the most emotionally potent points in his bassline, proof that some of the coolest moments in music can come from near-trainwrecks.

Halfway through the outro, Murray begins to stretch out with some sly note approaches to those stacatto downbeats, rounding out this delicious style study.

“At the end of '74, things were probably better than they'd ever been – every album we released was going straight to No. 1,” said Johnstone. “But Elton is the kind of guy who goes, ‘Okay, everything is going great – let’s change it up.’ He told me he wanted a new rhythm section, and he asked if I'd stay. I said, ‘I will, but I cant believe you're doing this!’”

Murray rejoined the band in 1980 for a live performance in New York's Central Park, then stayed on to work with John for his next few records. Murray suffered a fatal stroke in 1992 after a long fight with cancer.