The Albanese government is about to have to make a really important decision.

It’s going to have to decide what’s more important: supporting Australians who are financially under water, or keeping an election promise.

And it’ll have to do it soon. It’s already working on its May budget, now just six months away.

That choice will affect almost every Australian, and it could shape whether you’re thousands of dollars a year better off – or not – from July next year.

Household budgets are shrinking

When Labor took office in May 2022, Australians were doing well. Consumer spending and economic growth were on the up and up, and mortgage rates and rents were only starting to climb.

A promise to keep the proposed multi-billion dollar Stage 3 tax cuts – announced but not implemented by the Coalition back in 2018 – seemed worth making to clear away any reasons any voters might have not to vote Labor.

Since May 2022, just about everything has got worse for ordinary Australians – those on typical incomes, which are about $85,000 for full-time workers and $43,000 for adult part-time workers.

The best measure of the buying power of after-tax incomes is real household disposable income per capita. During the past year, it shrank 5.3%, which is more than it shrank in either the early 1990s recession or the global financial crisis.

On my calculations, it’s the worst collapse in 40 years.

From those incomes have to be taken rents and mortgage payments.

The Reserve Bank says scheduled mortgage payments are now taking up a larger share of household disposable income than at any time in history – 10% when averaged over all households including those that don’t have mortgages, and many times that for those that do.

This means when you go to the supermarket and find you can’t afford what you used to, you’re not imagining it. It hasn’t been like this in decades, and it’s about to get worse.

The Christmas bonus is missing

In the lead up to each of the past four Christmases, ordinary earners have received a bonus from the tax office - the so-called low and middle income earner tax offset, initially worth $1,080 and increased to $1,500 in 2022.

This year, it’s gone. It means middle-earners’ pre-Christmas tax refunds will be up to $1,500 smaller or replaced with bills. Taxpayers who normally have a tax bill will get a bill up to $1,500 bigger.

An estimated 10.5 million Australians submitted their tax forms by October 31.

Most of them – most of those earning up to $90,000 and previously eligible for the full $1,500 offset – are about to find themselves a good deal worse off.

Average earners will lose, while the rich get thousands

The very expensive Stage 3 tax cuts (costing $20 billion in their first year, and $313 billion over ten years) were meant to come to the rescue. They begin next July.

Speaking notes prepared for Treasurer Jim Chalmers and released under freedom of information laws say they will provide relief to low and middle earners and kick in at $45,000.

But someone on that income will get no relief. That person will lose an offset of $1,275 in return for a tax cut of zero. Someone on a higher wage of $50,000 will lose $1,500 in order to gain $125, and someone earning the typical full-time wage of $85,000 will have to lose $1,500 to gain just $1,000.

That’s right, a typical full-time worker will get relief of $1,000 from the Stage 3 tax cuts in return for losing the axed tax offset of $1,500.

Much higher earners will do much, much better. An Australian earning twice as much as is typical – $190,000 – will get $7,500. An Australian earning a bit more than that again – $200,000 – will get $9,000.

Labor has been handed an opportunity

Handing $9,000 to a high earner but only $1,000 to an ordinary full-time earner is an indulgence that might have seemed okay when it looked as if ordinary earners were doing alright, or wouldn’t notice.

But it’s about to happen, and it’s about to cost $20 billion in its first year. That’s as much as the government plans to spend on the pharmaceutical benefits scheme in that year and almost twice what it plans to spend on higher education.

What if it kept the tax cuts, but reoriented them to Australians who actually needed them – to the more than 80% of Australians who earn less than $120,000 a year – while still providing generous cuts to those who earned more than $120,000?

That’s a task Matt Grudnoff and Greg Jericho set themselves at the Australia Institute, coming up with four options. Each of those four would cost less than Stage 3 cuts; deliver more to Australians on less than $120,000 – and even fund a $250 per fortnight increase in the JobSeeker unemployment benefit.

Jericho’s punchline, delivered to the revenue summit at Parliament House last month: “I actually wish it was harder than it was”.

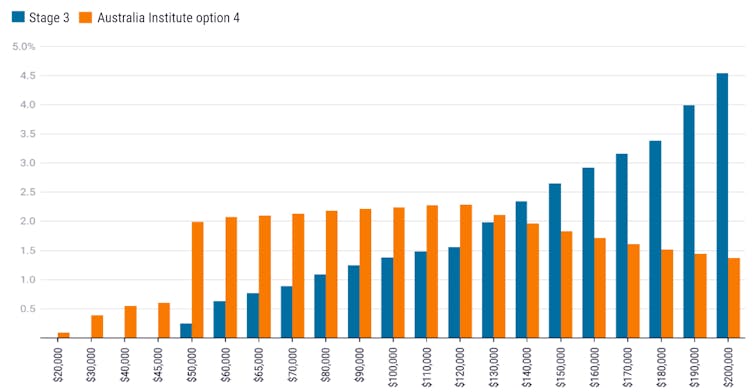

Option 4 costs $70 billion less over ten years but leaves every taxpayer earning up to $132,000 better off.

It doubles the tax cut Stage 3 gives to a typical full-time earner on $85,000, and still gives high earners $2,197 a year each.

Stage 3 vs Australia Institute Option 4, tax cut as percent of taxable income

His point wasn’t that this is the best option. It was that there are options, many of which give the bulk of Australians – the stressed ordinary voters Labor and the Coalition will need in the next election – much more than Stage 3.

What’s wrong with making 80% of the electorate better off at a time when they desperately need it, and cutting future budget deficits by $70 billion?

Only that it would break a promise, and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese likes keeping promises.

But when asked in an Australia Institute survey what was more important – keeping a promise or reacting to changing economic circumstances – 61% picked reacting to changing circumstances.

Even among Coalition voters, 56% supported reacting to changing circumstances.

It puts the Stage 3 tax cuts in play. There’s still time, and plenty of electoral and economic reasons to rejig them.

Peter Martin is Economics Editor of The Conversation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.